In 2015, an extraordinary production of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet took place in Belgrade and in Pristina. Performed in Albanian and Serbian by a carefully selected cast of Kosovo Albanian and Serbian actors, the play drew tears and heartfelt applause in both cities. Serbia’s Radionica Intergracije co-produced with Kosovo’s Qendra Multimedia. It was the first time that the administrations of Kosovo and Serbia have collaborated on a cultural event. For many of the actors, it was their first experience of meeting and working with counterparts from the ‘other’ side of a conflict that continues to divide along ethnic, religious and linguistic lines. Shakespeare’s play provided the chance to speak beyond these boundaries to people across the Balkans, and to reach an international audience as well.

For one actor in particular, a role in Romeo and Juliet, with its story of star-crossed lovers from warring familial tribes was an opportunity to lay some ghosts. ‘I myself am a product of a love story between Romeo and Juliet,’ says Uliks Fehmiu. ‘I felt very often I was a mistake. I asked myself whether my life would have been easier if, you know, the love wasn’t the product of parents who were from completely two different ethnic and religious backgrounds.’

Uliks is the son of the critically acclaimed Kosovo Albanian actor Bekim Fehmiu and Serbian actress Branka Petrić. Bekim was internationally recognised for his stage acting, and for his role in the film ‘I even met happy gypsies,’ by Alexander Petrović, which in 1967 won the Grand Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

By 1987, tensions across Yugoslavia were becoming unbearable for Bekim, an Albanian married to a Serb. ‘When everything started falling apart, it all of a sudden became a burden,’ says Uliks. ‘Because no matter what you say, no matter what you do, you are going to be perceived by either side as one of the opposition’.

One night, Bekim was on stage at the Yugoslav Theatre in Belgrade. Half way through the performance, he walked off stage.

‘Because of everything that was going on, as a sign of protest especially at the hate mongering that was going on against Albanians in the Serbian press, he was you know – thank you very much,’ Uliks says. ‘He withdrew completely from public life,’ a boxer, hanging up his gloves. The family left Serbia for America, devastating Uliks who was about to follow in Bekim’s footsteps with a place at the prestigious Belgrade Theatre school.

Bekim never returned to acting. He committed suicide in 2010. But for Uliks, his death came much earlier. ‘He actually committed two suicides,’ he says. ‘I think that the first suicide, his professional and artistic suicide, was something that devastated him the most and hurt him the most. This was when he was actually hurting. The second one was his very conscious decision to end his life when he felt he had no more reason to live.’

One night, Bekim was on stage at the Yugoslav Theatre in Belgrade. Half way through the performance, he walked off stage.

Twenty two years later, relations between Kosovo and Serbia remain politically and emotionally fraught, with small changes towards recognition and reconciliation coming at an incremental pace. The Serbian actor and director of Romeo and Juliet, Mikki Manojlovic wanted to make a statement and so Uliks was persuaded to return to the Belgrade stage and to appear in Pristina for the first time.

‘The reason why Mikki wanted to do this play was because everyone here is just talking. They are talking, talking, talking and nobody is doing anything,’ says Uliks. ‘Sometimes you need to start working before you are certain of the final result. And communication between people is apparently an extremely difficult thing but it shouldn’t be. I mean Belgrade to Pristina, what are we talking – it’s like 400 kilometres, I don’t even know. I live in New York, right, it’s the same distance from New York to Boston. And that you have this, how should I say, wall, of I don’t know what, through which you cannot penetrate, it’s utterly ridiculous. So I, as Romeo and Juliet’s son, how could I not participate and take the role that I did?’

That role was as the lynchpin character in Romeo and Juliet, Friar Lawrence.

‘Friar Lawrence is the only one who supports [Romeo and Juliet’s] love from the very beginning. Nevertheless, his support leads to tragic endings, but nevertheless he is the one who believes in love. I mean he believes in God, but he also believes in love,’ Uliks says.

It’s a powerful performance which highlights utterly just how central this character is to the lovers’ story. Friar Lawrence’s cell provides a safe meeting space for the lovers, it is where he presides over their wedding, where Romeo comes for advice and to hide after his banishment. Friar Lawrence makes the plan that sees Juliet fake her own death; he tries to get the message to Romeo and finally, it is he who discovers the lovers together, dead in the tomb.

For Uliks, playing this part in this version of the play was also a political act of reconciliation through language. As the Serbs attempted ethnic cleansing of Kosovo’s Albanian population in the 1990s, the use of Albanian language was repressed in public life; Albanian media outlets were shut down, and Albanian children did not have access to education in their mother tongue. With the help of the Kosovar actors and translators, Manolovic devised a script written in Albanian and Serbian, with actors from both backgrounds speaking both languages.

Uliks says, ‘Albanian is personally important to me because though my father acted in Serbian, English, French, Italian and in the Roma language, he never, except when he was an amateur actor here in Pristina in the national theatre, he never worked in his own language. So me being here, performing in his mother tongue it’s enormous emotional payback and I hope I did the language justice.’

These days, Fehimu is an actor living in New York with his Serbian wife and daughter. He says the sense of anger he had as a young man uprooted from his country and future is long gone.

‘I was angry that somebody had done this terrible injustice to us, you know, that our generation, that this older generation did something terrible to us who are young, our lives were just about to begin. I was waiting, I felt as if somebody had hit the pause button on my life and I felt I was waiting for someone to press play again and my life will continue. Then I understood that nobody was going to hit the play button, that there is no pause or play, that life that we have is the only one that we do, that victimising yourself and getting angry is not moving us forward. It can’t move us forward.’

At the after-show party in Pristina, he raises his glass to the young cast of the play. ‘Of course,’ he says, ‘you still have to work, you have to water it with love, and then if you start multiplying these little things, that is the only dream you can have: that love will keep on growing more love, that keeps on growing more love.’

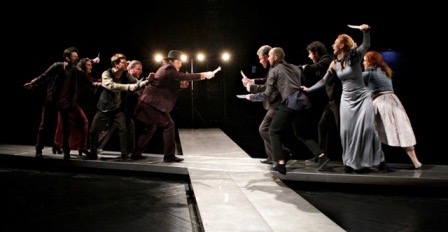

Banner photo by Maja Medić. ‘Romeo and Juliet’ produced by Quendra Multimedia (Pristina) and Radionica Intergracija (Belgrade).