This article was first published in the December 19th 2014 issue of NEWSWEEK

In a suite of rooms in a ‘safe house’ in a city in south eastern Europe, investigators employed by the British Government have been interviewing a stream of Iraqi civilians for the past 18 months. The questioners are members of the Iraq Historic Allegations Team (IHAT) and the men and women they are seeing are victims or witnesses of alleged unlawful killing and serious abuse at the hands of British Forces serving in Iraq between 2003 and 2008. The whole process is codenamed ‘Operation Mensa’.

Every month, a small group of IHAT staff travel to the safe house with a psychologist and witness supporters for a two-week stay. They are joined there by local interpreters who speak Arabic and a British lawyer representing some of the victims. The witnesses are flown in from Iraq especially for the interviews. They sometimes bring members of their families. One by one they are taken to a room where they are questioned. It can take days to go through their testimony. Evidence is monitored by CCTV in another room. Sometimes a specialist investigator watches and guides the interviewer’s questions. Their brief is narrow: they only want to hear about claims of unlawful killing or ill-treatment against the British. Any suggestion of a transfer to American or Iraqi forces, where they may have endured abuse too, is ignored. There’s no official interest in such stories. The experience of reliving their ordeals can be overwhelming. Occasionally, questioning has to stop. The effect of remembering every detail of every act of cruelty, of every demeaning condition, is difficult to predict. Many of the victims were only children at the time of their alleged abuse. There are those who say they still need care and psychological treatment because of the suffering they claim to have endured. They are given time to wander about the local city with their family, to calm themselves before beginning their testimony again.

Since March 2013, 83 Iraqis have been interviewed in this way – a small fraction of those who will need to be questioned. The High Court, which sanctioned the interviewing procedure, has heard from the Government and lawyers acting for the victims that there are now more than a thousand cases of killings and ill-treatment with more cases coming to light every day. If the UK is to fulfil its obligations to investigate each one fully, as it is legally bound to do, the process may carry on for years. But will those responsible for the crimes committed ever be brought to justice?

Hussain Baha Dawood Salim was six years old when his father, Baha Mousa, died from multiple injuries suffered whilst in British army custody in Basra. He’s now 16. Through a pre-recorded video, he says to an assembly of people gathered in London to commemorate the killing, ‘I can still remember when I was young how my father used to play with me. Now I’m left with nothing but memories.’ There is quiet in the hall as Hussain continues. ‘Why was he killed? I want to ask the British forces the reasons for torturing my father to death.’

In September 2003, Baha Mousa had just started working as a receptionist at a hotel in downtown Basra. Along with several other detainees he was arrested during a British Army raid looking for insurgents and taken back to a temporary detention centre for questioning. Over the next thirty-six hours, he was handcuffed, beaten, hooded and humiliated. He died during a final frenzied assault by his guard. The post-mortem revealed terrible injuries: broken ribs, bruises the size of footballs about his kidneys, ligature cuts across his throat and wrists. Ultimately the cause of death was pronounced as ‘positional asphyxia’. He had been unable to breathe whilst being pushed face-down onto the floor, his hands twisted behind his back and his head covered in a sandbag. The pathologist concluded that the many hours of mistreatment had left Baha Mousa incapable of withstanding this last battering.

‘Why was he killed? I want to ask the British forces the reasons for torturing my father to death.’

Despite an Army investigation, a court martial, a public inquiry and an announcement last year by IHAT that new lines of enquiry were being pursued, Hussain Salim’s question has yet to be fully answered. No one has been held accountable for his father’s death. Only a low ranking soldier, Corporal Donald Payne, was convicted of any offence related to the affair. He admitted the charge of inhumane treatment and was dismissed from the Army and sentenced to one year in prison. According to a senior army officer the incident remains a ‘stain on the British Army’, but it is one yet to be wiped clean.

If Hussain Salim’s plea for a reckoning in his father’s case has gone unheeded, so too have hundreds of others. Baha Mousa was not an isolated case. Over the past ten years, allegations have emerged of other unlawful killings, on the streets or in people’s homes or in British Army custody. Cases like that of Salih Hmood Matrood, an 8 year old girl who was playing near her home in broad daylight when she was allegedly shot by a member of the 1st Battalion of the King’s Regiment. Or 15 year old Ahmed Jabbar Kareem whom it’s alleged was arrested by a British Army unit, beaten and thrown into the Shatt Al-Arab River (a practice the soldiers called ‘wetting’) where, being unable to swim, he drowned. Or Abd Al Jubba Mousa Ali, a school teacher, who, by his son’s account, was arrested in his home by British soldiers, allegedly struck repeatedly with the butt of a rifle, taken away for questioning only to die in custody without any explanation. Or AJ Khalif, who was detained at an army road block, put in a military vehicle for transfer to a British base, apparently injured in a traffic accident on the way, only to be found later shot dead by the roadside. Or the more than 150 other reported deaths brought before the High Court. The Ministry of Defence won’t comment on these claims ´for fear of prejudicing´ any investigation, but it admitted in the High Court in 2013 that proper inquiries have yet to be carried out in 26 cases of alleged unlawful killing.

Allegations of the abusive treatment of Iraqi civilians detained by the British Army have also swelled in recent years. During the British presence in Iraq from 2003 until 2009, thousands of people were arrested, detained and interrogated. And from these, there are now more than a thousand cases alleging mistreatment, some said to amount to torture. Witness testimony speaks of beatings, sexual assault and religious humiliation, sensory and food deprivation, cruel interrogation techniques. Many victims say they were detained in these conditions for years without any explanation other than a standard letter stating: ‘It is believed you pose a security risk’.

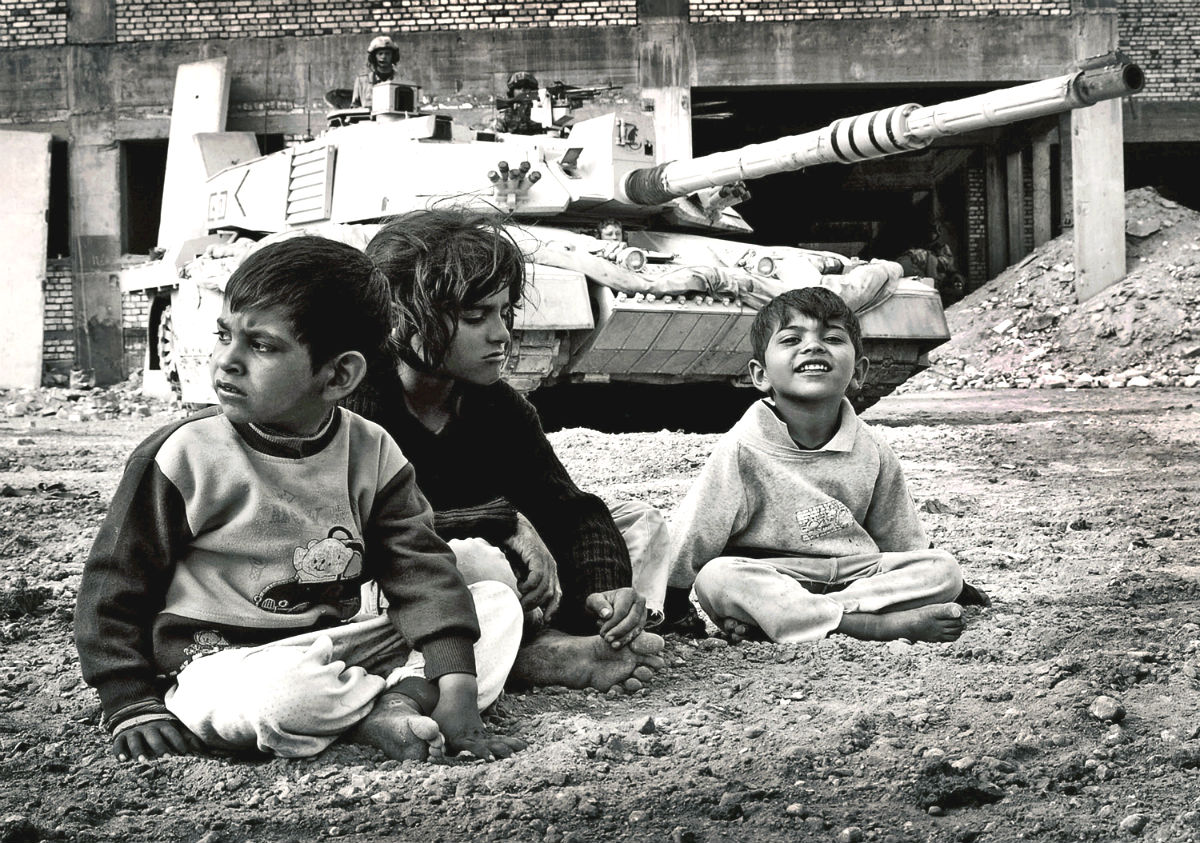

Iraqi prisoners. Photo by nafezaty

The MoD now accept that following the judgment in the Al-Jedda case at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, ‘people were detained without sufficient justification in ECHR terms. That is why we are paying compensation in many cases.’ But most allegations of ill-treatment remain unresolved. The testimony brought to the Court’s attention is compelling and indicates the scope of suffering alleged. Testimony such as that of the 13 year old boy arrested for suspected looting, then stripped naked and forced to adopt simulated sex positions with an Iraqi man detained at the same time whilst the soldiers took photographs. ‘They pushed the front of the other man’s naked body against the back of mine,’ the boy has said in evidence. ‘I could feel his genitals pressing against my backside. I felt so hurt and shamed’.

Another Iraqi civilian tells how he was arrested at a checkpoint in July 2004. Hooded and cuffed, he was taken to an Army base at Shaibah, outside Basra. There he alleges he was forced to strip in front of a medic and a number of soldiers before being taken to a tiny cell. The food was poor and little water was provided. Guards kept him awake during the night by banging on the door. When he was taken for interrogation the questioning seemed pointless. Once he was provoked by an interrogator who pulled out a copy of the Quran. The soldier lifted the ‘Quran up and banged it on the desk.’ It wasn’t the only time the Holy Book was used as a provocation in questioning. The detainee was kept in solitary confinement but never told why he was being held. Three years later he was released without a charge or specific allegation having ever been made against him. No consideration was given for the impact of the imprisonment on his family, his health and his business. The MoD will not comment on these allegations whilst IHAT is investigating them, though the claims are not unsubstantiated.

Lt Col Nicholas Mercer, one of the UK’s most senior legal officers serving in Iraq in 2003, gave evidence to the Baha Mousa Inquiry in 2010 that at one camp he had seen ‘forty prisoners kneeling or squatting in the sand with their arms cuffed high behind their backs with bags on their heads.’ He’d raised a written complaint but had been told that this was all ‘in accordance with British Army Doctrine’. The International Committee of the Red Cross visited in 2003 too and objected strongly about the treatment they saw.

When the hundreds of individual accounts are read together patterns of abuse are evident: the practices used in British detention centres across Southern Iraq, as described by the claimants, have a high rate of recurrence over the five years troops operated in the country. There are multiple allegations of forced nakedness; threats of rape against the detainee or their family members; coercion into simulated sexual positions; sleep deprivation; persistent and prolonged use of hooding with sand or cement bags in suffocating temperatures, even though the practice is known to be highly dangerous; sound bombardment; mock execution; the playing of pornographic videos outside cell doors; and beatings.

If the claims are proven, the patterns could indicate that the British military and government either failed to prevent systems of abuse developing or failed to investigate them properly. They might even provoke the question: were they sanctioned?

But is the evidence enough to pierce the conscience of a nation?

For many years, the British Government’s position was typified by the author of a report commissioned by the Army into some of the early allegations. Brigadier Robert Aitken wrote in 2008, ‘We can be assured that the great majority of officers and soldiers who have served in Iraq have done so to the highest standards that the Army or the Nation might expect of them, under extraordinarily testing conditions.

There is no evidence of fundamental flaws in the Army’s approach to preparing for or conducting operations’. It was acknowledged that some lessons needed to be learned, but any abuses were impliedly the product only of rogue elements, soldiers who had acted unlawfully on their own initiative, ‘rotten apples’.

If anyone has challenged this received wisdom it is Phil Shiner. Over the past ten years he has been responsible for bringing most of the allegations to light. A private lawyer operating out of a small office in Birmingham, UK, he first began to represent Daoud Mousa, Baha Mousa’s father, in his pursuit of the truth about his son’s death. Since then, Shiner has acted for hundreds more claimants, challenging the Government in a series of court cases for its failure to investigate and prosecute those responsible for killings and abuses. His doggedness has turned him into something of a bête noir for the British establishment. So much so, that the Ministry of Defence was reported by the BBC in May as feeling he was ‘dragging the British military’s reputation through the mud’, though the MoD won’t comment on the remark as it wasn’t attributed to any particular official.

The implication, however, that there would be little cause for concern, but for the legal cases brought by Shiner and his firm, Public Interest Lawyers, epitomises the British Government’s unwillingness to get to grips with the allegations, Shiner says. ‘The Ministry of Defence are trying to make it look as though I’m the problem. But that’s a deflection. This isn’t about me or any other lawyer legitimately seeking justice for their clients through the courts.’

‘The real problem is that the government and particularly the Ministry of Defence have consistently refused to do what’s necessary to get to the truth,’ says Shiner. ‘Years have gone by when they should have been dealing with all these claims. Despite all the evidence, they’ve put every obstacle they can in our way. My clients have had to take the Government through our entire legal system, to the highest courts and then on to the European Court of Human Rights to have the accusations taken seriously.’

To add to the barriers, the Government has tried to introduce new rules for legal aid that will arguably prevent claims from Iraq or anywhere overseas. Judicial review of failures to investigate unlawful killing or ill-treatment by British Forces will only be funded if a claimant has been resident in the UK for 12 months when applying for legal assistance.

It’s as though the system is doing all it can to make sure there will be no accountability.’

Shiner says, ‘None of the cases I’ve pursued in the courts, the Baha Mousa Mousa case in particular, would have been possible if this rule had been in place in 2004. It’s as though the system is doing all it can to make sure there will be no accountability.’

The rules were declared discriminatory and unlawful by the High Court in a judgment on 15 July. Lord Justice Moses specifically mentioned that those who suffered serious abuse at the hands of the Armed Forces abroad would be illegally affected by the proposed restrictions. But despite the court’s decision, the rules could still be introduced if the Government forces the matter.

It was in March 2010 that the Minister for the Armed Forces first announced the creation of an Iraq Historic Allegations Team (IHAT) would be established. The team was to consist of a large number of Army Police. Shiner and his firm objected on behalf of dozens of victims. ‘It was a case of the Army investigating themselves again,’ he says.

The court agreed. The investigators had to be independent according to standards set down by the European Court of Human Rights. It then took until 2013 for a team of Royal Naval Police and ex-civilian police to be declared as satisfying that legal requirement. The Team is now run by Mark Warwick, a retired Thames Valley Police Officer who’s familiar with commanding complex case investigations. He and the IHAT team work out of an army base in Upavon, Wiltshire.

The scale of the task that Warwick and IHAT faces is immense. The High Court, when confronted with evidence of the huge number of accusations ‘of the most serious kind,’ described the duty to investigate and prosecute the crimes as ‘unprecedented.’ And the cases referred to IHAT have grown steadily: In 2011 IHAT had 97 separate cases to contend with. Now, it says on its website that it’s dealing with more than 1000 allegations of unlawful killing or mistreatment.

These numbers are bad enough, but the logistics seem overwhelming. Not only does IHAT have to complete the viewing and analysis of thousands of hours of video-taped interrogations carried out in British detention centres in Iraq, tapes that might provide evidence of ill-treatment, it also has to deal directly with the individual claimants and those who may have witnessed crimes. Operation Mensa is an important component of that latter task. The interviewing of the Iraqi witnesses and victims has to be conducted according to standard ‘achieving best evidence’ principles, says Warwick, principles which guide police interviewing of victims and witnesses of crimes in the UK.

Shiner is highly sceptical about IHAT’s confidence in finishing investigations anytime in the near future. ‘By any reasonable standard, the current pace of investigation is wholly inadequate,’ he says. ‘The victims and families could be waiting 15 years for their case to be resolved. And that takes no account of tracking down and interviewing suspects in the Armed Forces.’

Nor does it consider any delay by prosecutors in charging and bringing those suspects to trial.

The man responsible for prosecuting members of the Armed Forces works out of a large comfortable office in the heart of the Royal Air Force base in Northolt, West London. He knows about the danger of delay. Andrew Cayley QC, Director of the Service Prosecutions Authority (SPA), the body responsible for prosecuting all crimes committed by armed forces personnel, used to be the Chief International Co-Prosecutor of the Extraordinary Tribunal in Cambodia.

For four years he was responsible for prosecuting some of those Khmer Rouge members accused of genocide and the worst forms of crimes against humanity in Cambodia during Pol Pot’s infamous rule in the 1970s. Before that, he worked at both the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the International Criminal Court. He also served in the British Army’s Legal Service for a number of years in the early 1990s. His experience in international criminal trials is second to none.

‘Delay is an issue I’ve confronted throughout my career,’ he says. ‘If you look at the international courts, some of the delays there are far too long. In terms of international standards, we’re working much more quickly and efficiently. Of course it’s a concern. But people are well aware of this.’

He couldn’t comment on Shiner’s estimate of how long the Iraq allegations might take to complete. That was a matter for IHAT. At the investigation stage, his team’s involvement is advisory. Every 6 to 8 weeks, members of the SPA’s Iraq Historic Allegations Prosecutions Team, meet with IHAT to review the progress of cases. Cayley says they ‘discuss what steps need to be taken in order to bottom this out as far as we can with the resources we have.’

But resources are limited. The SPA’s Iraq team is currently staffed with five lawyers. None of them are serving Army personnel. One is from the RAF, another from the Navy, a retired Air Force lawyer has just joined and there are two civilian lawyers seconded from the Crown Prosecution Service. Cayley’s predecessor, Bruce Holder QC, decided to bring them in ‘out of an abundance of caution,’ says Cayley. It was decided that there should be a ‘Chinese wall’ to avoid claims of lack of independence, the same criticism that was directed at IHAT when first established.

Whatever manpower is available, the number of prosecutions that have been brought since IHAT began its operations in 2010 remains fixed: none.

But the SPA has to do more than advise on individual cases. Its lawyers also have to think about systemic issues: those patterns which indicate some criminal responsibility higher up the command chain for illegal interrogation or detention methods used as standard operating procedure in Iraq.

‘These are evidence led investigations,’ Cayley stresses. ‘The minds of all of us are open to systemic issues. At the moment I make no comment at all about whether there is any evidence that exists.’ But Cayley is convinced that IHAT is looking carefully. ‘There are policies in place so that if evidence does arise that demonstrate systemic matters, it will be picked up … it is in people’s minds’. And, says Cayley, ‘Trust me. I will recognise it when I see it.’

The need to be alive to allegations that the many killings and cases of inhuman treatment indicate problems at the heart of the Armed Forces and government, was amplified in May this year. Fatou Bensouda, Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in The Hague, announced that she was opening a preliminary examination of the UK’s record in Iraq. New information had been received that ‘alleges the responsibility of officials of the UK for war crimes involving systematic detainee abuse’. A 250 page dossier with bundles of evidence was served on the Prosecutor in January 2014. It had been produced by the Berlin based European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights and Shiner’s Public Interest Lawyers and repeated the many unresolved allegations. There has been a failure by the UK Government to properly investigate and prosecute individual crimes, the dossier said. It alleged that there is credible evidence of ‘widespread and systematic abuse of detainees … ordered, sanctioned or enabled by higher level officers within the military chain of command, and with the knowledge of higher level civilian officers’.

Fatou Bensouda, the ICC Chief Prosecutor, is an impressive figure. Once a senior minister in the Gambia, she joined the ICC in 2004. On the retirement of Luis Moreno-Ocampo, the first Chief Prosecutor, she was appointed to his role and instantly made known her determination not to allow the court to become concerned only with dire wars in the heart of Africa.

Though focus might remain on the worst atrocities found in the Congo or Darfur, she has been quick to react to claims about the situations in Libya and the Ukraine. She could not ignore, then, the accusations against UK personnel. Her predecessor had received initial complaints about the situation in Iraq in 2004, including as to the circumstances of the death of Baha Mousa. But it took him two years to respond. Mrs Bensouda’s announcement took four months.

The ICC’s proclamation provoked a quick response from Government ministers. Dominic Grieve, the Attorney General at the time, denied the need for the ICC to get involved, rejecting claims of systematic abuse but promising complete cooperation.

For her part, Chief Prosecutor Bensouda says her Office is duty bound to assess the British proceedings ‘to see whether they are being undertaken genuinely.’ ‘Undue delay,’ she says, ‘may be considered, for our purposes, an indication of the unwillingness or lack of genuineness to carry out the necessary investigations and prosecutions.’ They will also be looking at any patterns of abuse and seeing if the British authorities are responding to these if they are apparent from the evidence.

Royal Marines OP TELIC. Photo by Thomas McDonald

On 7 July this year, the Ministry of Defence quietly published its first statement on ‘systemic issues’ purportedly revealed by all the information collected from completed investigations so far, including, it says, an analysis produced by IHAT of all the thousands of hours of video footage of interrogation sessions taken in Iraq (which it has called Operation Twickenham). It was released so quietly that even Mark Warwick as head of IHAT didn’t know about it. Although the statement claims the issues mentioned do ‘not necessarily mean that these failings actually occurred’ it would make little sense unless evidence of ill-treatment in Iraq had been identified.

‘If you read between the lines,’ says Shiner, ‘you can see how appalling the approach to detention and interrogation must have been in Iraq. Every issue the MoD’s paper mentions has been the subject of multiple allegations brought by my clients. Just look at all the things it says the Army needs to be concerned about. Why set out all these precautions if there isn’t evidence of wrongdoing in each case? It’s absurd.’

Just look at all the things it says the Army needs to be concerned about. Why set out all these precautions if there isn’t evidence of wrongdoing in each case?

The list of issues to be addressed relate directly to accusations brought before the courts. They include the need for ‘training courses to make clear that captured persons should not be humiliated’, ‘timely provision of water’ and ‘food to detainees’, the need to prevent ‘sleep deprivation’, subjecting ‘detainees to loud noise’, ‘assaults on detainees’, the need ‘to ensure medical treatment is provided in cases of obvious urgent need’, ‘to avoid delay in the reporting of deaths to service police’, and ‘ensure humane treatment’. In each case there is no mention of practices in Iraq during 2003 and 2009, only on how the Army has put in place good procedures since. The interrogation and detention policies referred to are either dated 2011 or later.

‘Why write all this unless there’s suspicion that these needs haven’t been met?’ asks Shiner. ‘And if there is suspicion, why not admit it? Even if they don’t go that far, there’s surely enough here to say: there must be a full and public inquiry into all these matters. The public’s right to the truth must be respected. If not, the British people are just going to be kept in the dark.’

Hussain Dawood Salim knows what happened to his father. Nearly every detail of his arrest and detention and death was laid bare in a report issued by a protracted public inquiry (called the Baha Mousa Inquiry) in September 2011. But he still doesn’t know why it was allowed to occur.

No one has explained to him how it is that his father could be kept in the middle of an Army base, subjected to torture and finally beaten to death without any officer or medic or other soldier intervening. Even now IHAT cannot say why it is pursuing new lines of enquiry. The SPA cannot tell him when or if prosecutions will be brought against those individuals, both officers and rank and file soldiers, named in the Baha Mousa Inquiry report as responsible for assaulting him or failing to protect him. Perhaps in time someone in a position of authority will be prosecuted for this failure. But the signs are not good. Eleven years have now passed since Baha Mousa’s death.

And how likely will it be that anyone high up in government or the military will be held responsible for the systems of abuse that were operated in Iraq over the six years British forces were stationed there? If the ICC take more of an interest than a watching brief, the UK Government might be forced to act. Otherwise individual litigation by one lawyer and his firm is the only significant challenge to the active indifference so far displayed by politicians and Ministry of Defence officials.

If there is to be some reckoning for what happened when British forces operated in Iraq, it won’t be decided in Basra. The geography of justice in these cases may lie now between a bijou office in Birmingham, a functional suite of rooms in the middle of an RAF base outside London, an Army base in Wiltshire, and a sleek architectural monstrosity in The Hague. But true accountability is only likely if there’s a change of mind and culture in Westminster, at the heart of political power in Britain. So long as the Government’s position is to wait until all possible investigations and prosecutions have been completed before considering a public inquiry into what went wrong in Iraq, there is unlikely to be any reckoning. And Salim’s question, and that of thousands of others, will remain unanswered. The battle for the truth and for accountability is likely to last for sometime yet. ‘What my clients want is recognition of what was done to them or their loved ones,’ says Shiner. ‘They want justice. And so should we.’

Photo by Thomas McDonald