Many reviewers of Zero Dark Thirty (2012),Kathryn Bigelow’s fictionalisation of the decade-long manhunt for Osama Bin Laden, concluded that the film condones torture.

Critics suggested that the film was essentially propagandist and an apology for real political torture.[1] Yet other reviewers had more ambivalent views or even read an anti-torture message in the film; as a prominent example, filmmaker Michael Moore claimed the film would make spectators hate torture. How does Zero Dark Thirty manage this “litmus test”[2] effect, to function like a “white-on-white canvas, […] a projection screen for the audience’s perceptions and sympathies” [3]?

The single most contentious issue of this film is its treatment of torture. In recent years, audiences have been treated to a number of shows and films in which torture appears as a convenient dramatic device to propel the narrative towards a solution. The executive producers of the long-running popular? Fox TV show 24 (2001-2010), for instance, admitted to employing torture routinely as a time-expedient shortcut. While Zero Dark Thirty does not use torture as a kind of miracle tool, a truth-generating magic wand, the film’s representation does follow certain movie conventions.[4]

In Zero Dark Thirty, torture affirms the resolve to catch Osama bin Laden at all costs, without having the law “tie one’s hands behind the back.“ [5] In what has been described as a ticking bomb scenario within the omniscient narrator fallacy,[6] the torturers possess almost all necessary information with absolute certainty: they know an attack is planned (the bomb is ticking), and they know their prisoner is the person who has the necessary information to prevent the attack.In a quantitative weighing of evil, it is insinuated that torture – the sacrifice of the humanity of one – is morally permissible, even virtuous, to prevent an imminentattack and save the lives of many.[7] This locates the ethical dilemma with the torturers. The torture is turned into a heavy personal weight for the torturers; the worse the inflicted pain, the greater their personal burden. The graphic messiness of the torture scenes in Zero would then serve to reinforce this Eichmann Syndrome, in which the perpetrator considers his acts as duty and a heavy cross to bear.[8]

Zero Dark Thirty

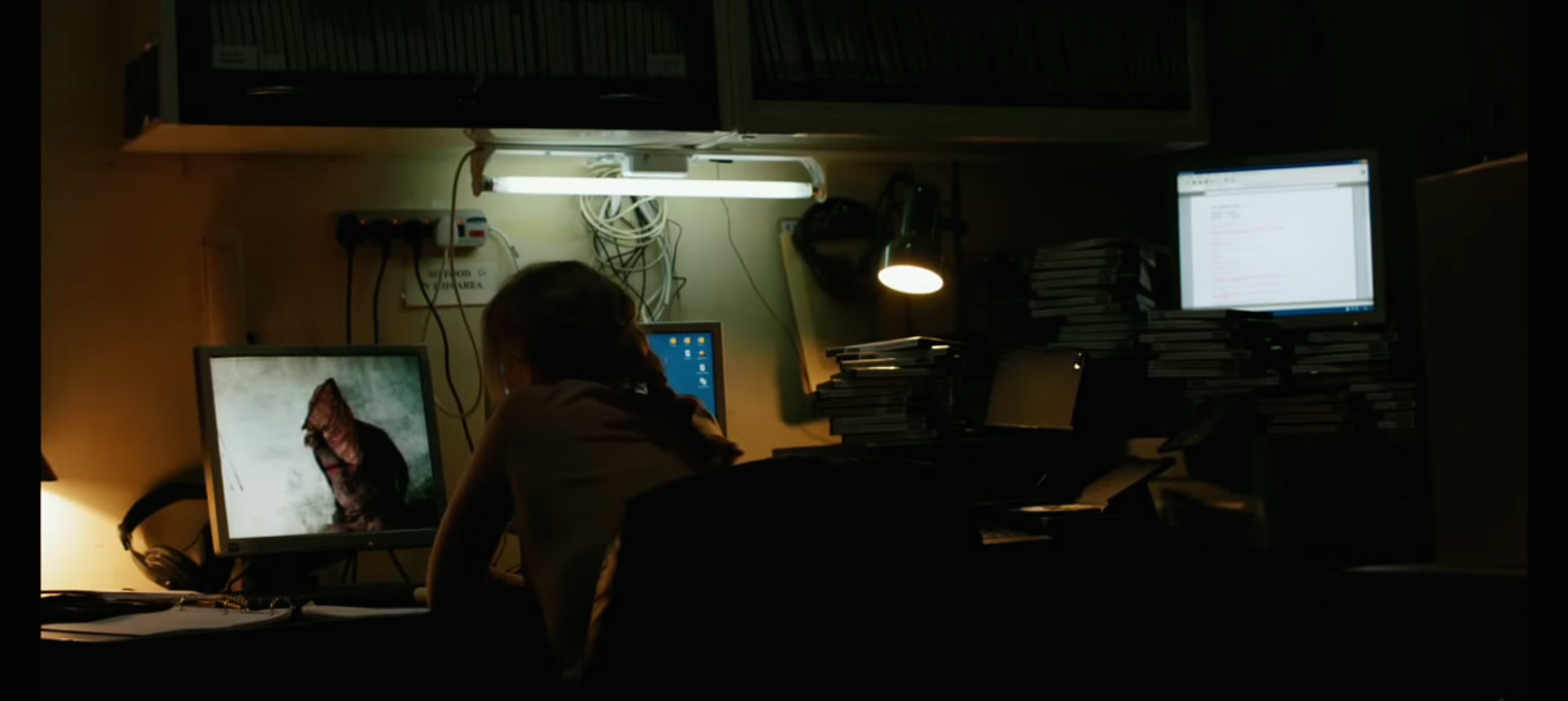

The audience is mostly aligned to the perspective of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) personnel. For instance, like the CIA torturers (but unlike the prisoners), the spectator is allowed to see both the inside and the outside of the prison compounds. The agents, played by familiar and attractive actors, might be more relatable than the little known performers who play their detainees. One of the tortured victims, Ammar, is shown to be an unrepentant and fanatical terrorist, spouting ideological gibberish. His coolly detached torturer retorts with jokes and polished swagger.

A viewer’s pre-existing political vision seems then more decisive in the distribution of sympathy towards the characters.

The story of Zero is presented through the eyes of CIA operative Maya, whose stance on torture changes over the course of the film. Initially reacting on a spectrum between disgust and moderate empathy, Maya eventually resorts to using torture herself. The development, and the audience’s perceived alignment with Maya, is used as evidence by those who argue that the filmadvocates torture. Yet in her proclivity to use violence – in one scene Maya suggests dropping a bomb on account of one of her hunches – Maya also appears slightly unhinged. For her, the killing of Osama bin Laden turns into a personal quest. Nicknamed “the killer,” she has been born, or, as she says at one point, “spared”, to kill him. And although our perspective is personalised, channelled through Maya, the audience is offered little emotional detail so as to feel closer to her, or to any other character for that matter. A style of detached realism, and the absence of any history or personal detail of the characters, results in a disengaged coolness of delivery. A viewer’s pre-existing political vision seems then more decisive in the distribution of sympathy towards the characters.

Yet, the question remains: does this alignment with the CIA necessarily justify the use of torture?

The representation of professional torturers in the film belies the initial accounts that emerged from the torture scandals during the Iraq conflict, namely the notion that the torturers were aberrant “bad apples”, spurned by overconsumption of violent media and pornography.[9] In December 2014, the Senate Intelligence Committee finally released an Executive Summary of the so-called “Torture Report”.[10] This report confirmed that the CIA rendition and detention programme was ordered and sanctioned by a chain of command, countering the narrative that the events at Abu Ghraib, Basra, and other places resembled an (inexplicably sadistic) frat house on spring break.

Moreover, in the words of Mark Osiel, it might be “a mistake to overestimate the gap between the moral universes of [torturing] officers and civilians”:[11] In an essay on the mental state of torturers in the context of Argentina’s Dirty War, Osiel shows that the torturers did reveal an awareness of facing a moral conflict and displayed a strong “sense of moral obligation”. Could it just be the normalcy of the perpetrators in Zero Dark Thirty that feels so terribly uncomfortable to the audience? The torturers in this film are not monsters: they do not exist in a separate existential realm, and neither, perhaps, do the real torturers. For the same reason, it felt uncomfortable when, in August 2014, Barack Obama said: “We tortured some folks”. True, in contrast to then-Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, who in 2004 refused to address what he called “the torture word“ [12], Obama admitted theuse of torture. At the same time, his choice of the word “folks” seemed to scale back the impact. These were just some folks torturing some folks – would such a sentence really succeed in transforming torture into a normal procedure?

Could it just be the normalcy of the perpetrators in Zero Dark Thirty that feels so terribly uncomfortable to the audience?

Another argument why Zero might appear to sanction the use of torture is related to the opening montage. After the epigraph, which announces to the audience a film “based on firsthand accounts of actual events”, Zero opens with a black screen and archived audio recordings of distress calls of people trapped in the World Trade Center towers on September 11, 2001. These harrowing last words of people locked in the burning Twin Towers generate an emotionally loaded atmosphere. As the only contextualisation for the immediately following torture scenes, torture emerges as defensive response to terrorism. Framing terrorism as the justification for, and the cause of, torture conceals the United States’ long history of using torture, the development and export of torture techniques, and the training and funding of torturers. To present torture this way helps to perpetuate an historical amnesia that also characterises public discussions on torture. Equally omitted from the film are the dissenting voices within the government and its agencies, fights about (il)legality of the practice that accompanied the real-life implementation of the CIA torture programme.

The credible threat of, and option to use, torture are depicted as critical tools in the first torture scene. After having been extensively tortured, prisoner Ammar is offered some food and threatened with further torture should he continue to withhold information. The fact that Ammar had been tortured seems important to establish the credentials of his adversaries: they mean business, and Ammar relinquishes the desired information.

The film builds here on the logic and strategies described in a real CIA manual used during the Iraq War, which was based on psychological and anthropological ideas of the 1970s – and, in particular, from a book infamously titled The Arab Mind. The scenarios envisioned here – that a prisoner must and can be reduced to a psychological “complicit stage” through torture – are not backed up by the experience of real interrogators. Army educators and FBI interrogators complain that this kind of 24-logic has been steadily adopted by new interrogators, when, in fact, the lengthy process of rapport-building with detainees, over long periods of time, is confirmed as a more productive way to elicit information. The film shows this threat of torture as blatantly effective in other cases as well. One interviewee, for instance, is threatened with delivery to Israel – implying and assuming the audience’s knowledge regarding Israel’s real use of torture. The detainee immediately cooperates:“I have no wish to be tortured again. I will tell you what I know.” In reality, any testimony obtained through torture is notoriously unreliable. The tortured might well not know anything, might be lying or telling the truth, might never “crack”, or might just pretend to crack. For instance, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, identified as “the principal architect of the 9/11 attacks” by the 9/11 Commission Report, was extensively water-boarded (a technique that emerged as one of the most controversial “enhanced interrogation techniques” from the War on Terror). Despite suffering the procedure a total of 183 times, Mohammed only gave false information.

As far as the case can be made that Zero is critical towards torture, it is not on a fundamental or ethical level, but on a utilitarian level. It is conceded, in convoluted fashion, that torture did not retrieve the desired information to catch bin Laden; but torture in the film appears less problematic in and of itself. Frustratingly, the public debates of real torture also remained focussed on the utility of torture. The 2004 torture debate, after the release of the Abu Ghraib photographs, was essentially repeated in its limited reach when Zero opened in 2012, and when parts of the Senate Investigation were released at the end of 2014. Thus, both the debates on real torture and those on the film’s ideological position remained centred on who gave which information and when. What need to be challenged are the premises of this utilitarian framing. What needs to be made clear is that the scenarios used to justify torture are fictitious, that torture is never the most productive tool to obtain information, and that the acquisition of intelligence is not why detainees are tortured.

The film’s director Kathryn Bigelow has argued that we cannot know whether the U.S would have captured Osama bin Laden without using what she described, rather tellingly, as “harsh interrogation techniques”.[13] (The unknowability defence echoes a similar line of defence from within the CIA, one that comes closest to admitting a problem with the detention program.) Bigelow’s argument, that the audience should be “trusted” to make up their mind about her film independently, seems somewhat disingenuous, as any film necessarily invites a political and moral position through its aesthetic and narrative strategies. Empathy with the victim is certainly not a privileged viewpoint in Zero. Even in her “softest” moments, Maya’s disapproval of torture always resembles disgust at the messiness of it all, rather than genuine compassion. Does this mean then that the film encourages the approval of torture, that the filmmakers meantfor us to condone its use?

I believe that these are the wrong questions. Zero Dark Thirty raises other, more important issues, which relate to the factual torture cases that continue to be sidelined. For instance, what will happen afterwards with the prisoners shown in the film? There are scenes taking place in settings that visually resemble Guantánamo, while Maya and the audience are informed early on that Amman will never get out. If terrorism caused, necessitated and justified the torture, how can it have ended? The death of Osama bin Laden, while closing one particular narrative, neither ended terrorism nor the ineptly named war on it – a fact viewers of the film have been reminded of for over two hours through repeated terror attacks.

When we witness a representation, we have a bodily response that feels true, and this reaction stabilises the rhetorical slipperiness of the representation.

What does it mean to see images of torture? Do we have a moral obligation to witness (also record, screen) pain, or does our passive watching make us complicit in the brutality? Recently, spectacular depictions of violence have included the beheadings of captured journalists and soldiers by Islamic militants, but torture has been utilised as a rhetorical device as far back as ancient Greek tragedies. In her work on these plays, Jennifer Ballengee emphasises the ambiguity in the representation of torture. The body in pain may be read as a tragic victim of sadism, a portrayal of misery as suffering legitimate punishment: “Torture’s rhetorical intent, as it is represented before an audience, demands interpretation; it solicits a verdict.” [14] The audience make this moral and aesthetic judgment following a visceral reaction.When we witness a representation, we have a bodily response that feels true, and this reaction stabilises the rhetorical slipperiness of the representation. Whether as spectators of Greek theatre or a modern movie, the audience thus remains central to determining what pain being inflicted on a body communicates.

As an audience, we are able to distinguish between a film and reality. We can focus on what a film can show and do well, rather than lament its limitations. This seems more important than a continued debate on historical details (as irksome as some alterations may be), on the truthfulness or the objectivity of (any) film. We may use Zero Dark Thirty to explore where this film evokes uncomfortable feelings, tensions which might reflect our own ambivalences, helplessness, and confusions.

Zero is not a film aimed at “setting the record straight”: We know how this story ends.But we should not be mistaken to think we know the whole story, and the real story has not ended yet. What is the point of telling it, if not to turn the story into an experience, and to turn us into witnesses? We have the choice to become participants in transforming this story.

[1] Greenwald, Wolf

[2] (Brody, R., December 12, 2012b),

[3] (Winter, J. & Rothman, L., 2013: 25).

[4] We have become accustomed to such conventions on screen, how, say, protagonists routinely order “a beer” as if there were only one kind, how audiencesknow when someone bleeds from the mouth onscreen it is a sign that they are mortally wounded, and how a character being electroshocked in a movie is seized by violent spasms.

[5] The Israeli Supreme Court Judge Ahron Barak, in a 1999 landmark decision against the use of torture/that torture was illegal, insisted that a democracy needs to fight terrorism “with one hand tied behind its back”, i.e. bound by the rule of law.

[6]Marks, J. H., 2010

[7] cf. Dershovitz, A., 2004.

[8]Hannah Arendt writes about Eichmann’s trickery to position himself as victim instead of culprit: “the trick […] consisted in turning these (human) instincts around, as it were, in directing them toward the self. Instead of saying: What horrible things I did to people!, the murderers would be able to say: What horrible things I had to watch in the pursuance of my duties, how heavily the task weighed upon my shoulders!” Arendt, H., quoted in Scarry, E., p. 58.

[9] Former Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, head of the fifth investigation into the prisoner abuse at places like Abu Ghraib and Basra, characterised the incidents at Abu Ghraib as “Animal House on the night shift”, which was transformed into the “bad apple” narrative, cited in Danner, 2004: xiv; cf. Butler, J., 2010; McClintock, 2009.

[10] The official name is of the report is “Committee Study of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Detention and Interrogation Program“. The focus of the report was to document torture’s ineffectiveness, not its illegal nature.

[11]Osiel, M., 2006: p. 135.

[12] Hochschild, A., 2004.

[13](BBC interview January 2013).

[14] Ballengee, J. R., 2009, p. 144.