This month will see the 70th anniversary of the Nuremberg Tribunal when twenty three leading Nazis were put on trial. Andrew Williams writes about his new book, A Passing Fury,to be published by Jonathan Cape next year, which looks beyond the myth of Nuremberg and to the largely forgotten scheme of justice undertaken by Britain and its Allies after 1945.

Later this month falls the seventieth anniversary of the Nuremberg Tribunal. There’ll be familiar grainy newsreels of Nazi leaders in the specially constructed dock, a pontificating Goering grandstanding before the microphone, solemn faces of prosecutors and judges.

We’ll no doubt be shown films of war and slaughter and brutality and hear pronounced, in some recording (just audible through static), the sentences of death by hanging.

So the myth of Nuremberg will be repeated: this was the moment when a system based on evil was conquered by a system founded on law, when those individuals responsible for the most abhorrent of crimes were brought to justice, were fairly treated, were fairly tried and were fairly punished. And this was the moment when international criminal justice was born, when the precedent was set to end impunity, to make accountable those political and military leaders, as well as the direct perpetrators, responsible for the worst of crimes.

A vast scheme of retribution was planned, delivered and ultimately betrayed

But like all myths, Nuremberg (it’s enough seemingly to say the name to capture the whole sense of justice done after the Second World War) represented only a fragment of the truth. Between 1945 and 1949 a vast scheme of retribution was planned, delivered and ultimately betrayed, by the Allies (the Americans, British, French and Soviets). Nuremberg was but its symbolic core. Around the circus of that great trial (the trial of the century according to some), revolved thousands of investigations and prosecutions with the intent of bringing every German war criminal to account. A failure of nerve and a failure of political will saw this ambition quickly dissipate.

Over the last five years, travelling around Germany, hunting through archives, accumulating mounds of material, I’ve tried to uncover some of this extraordinary and largely untold and much more complex tale of post-war justice. My search was initially triggered by a chance encounter. In 2010, I happened to visit Neuengamme, a small town in the outskirts of Hamburg. I’d never heard of the place before, but whilst passing through the city I read about a memorial there which piqued my interest. It was the location of one of the Nazi’s concentration camps that had been liberated by the British army in May 1945.

My visit was predictably harrowing. Walking about the old barracks and execution cells, the medical experiment centre and crematorium, is a visceral experience. The suffering of the camp inmates is made plain at every step, though it’s in the House of Commemoration, set in a little plantation of conifers in a distant corner of the site, that the sheer scale of abuse is most apparent. There, I was confronted by white scrolls hanging from the ceiling to the floor. Each one had three columns. Names of the camp prisoners who’d died were clustered under specific dates. The record began in 1938 when the camp was opened. It ended in May 1945. Some days, the earliest, had only one or two names beneath. Dates in later years had more than I could count by sight. And one day, 3rd May 1945, at the very end of the war, had thousands written below. Name after name, scroll after scroll. There was no explanation, not that much explanation was needed I first supposed. Though Neuengamme wasn’t a site of extermination like Auschwitz or Treblinka or Belzec, Jews, common criminals, political detainees, Soviet soldiers, French resistance fighters, Dutch underground, people from across Europe had all been subjected here to the most brutal treatment. Their lives were worth nothing. What I didn’t know then was that most of those listed under 3rd May, nearly 7000 of them, had been killed by the British in one of the largely forgotten tragedies of the War.

Despite the unrelenting stories of death and torture and every-day cruelty, I thought I’d found across the camp some sign of a reckoning for these crimes. Near the barracks was a single storied set of buildings, the SS garages, where the camp automobiles were serviced. Signposts pointed the way to an exhibition inside that examined the ‘relationship between individual deeds and individual responsibility’. It happened to be the very question troubling me then, writing as I was about the death of Baha Mousa, a detainee killed by British soldiers in an army base in Basra 2003, provoking a court martial in the UK that saw no one held responsible for his homicide.

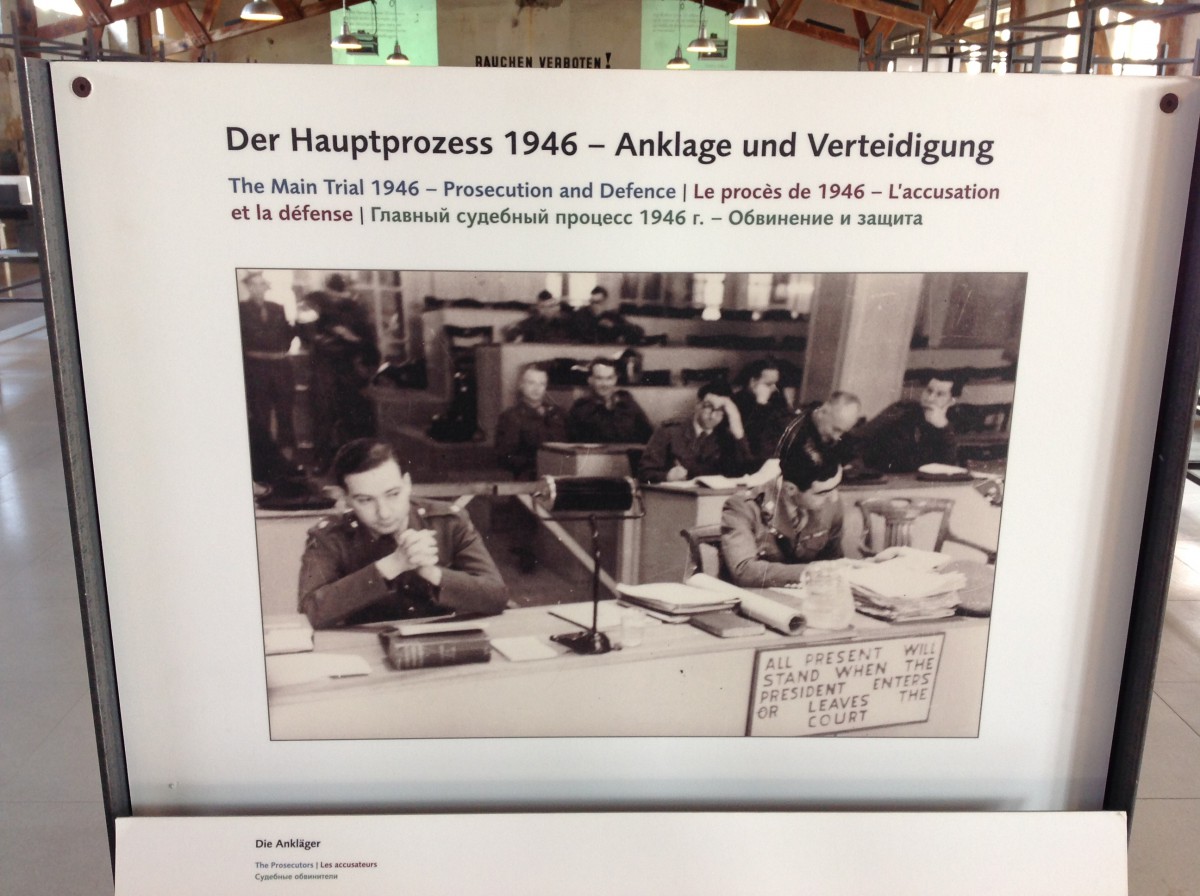

Immediately within the exhibition was a display of black and white photographs. They were very different from all the other pictures in glass cabinets or on walls about the camp. One showed a fresh-faced, dark haired young man in British uniform, sitting behind a desk, his hands clasped just beneath his chin, a textbook and notepad on the table before him. He was looking askance at something or someone out of shot. To his left, also behind the table, was another soldier, who sported a few more medals and braiding and an air of seniority. He had his head down, looking intently at a sheaf of papers.

Neuengamme trial

Photo by Andrew Williams

The caption beneath the photograph identified the man on the right as Major Stephen Malcolm Stewart. He’d been the senior prosecutor at the main trial of the Neuengamme camp SS personnel, begun in March 1946 in a makeshift courtroom within an old building in the centre of Hamburg. The trial had apparently been a British affair, British lawyers, British judges, British guards, and had been held at the same time as the Nuremberg Tribunal, but, said the exhibition literature, had been quite independent of those proceedings.

Of course, I knew about Nuremberg. That tribunal provided the precedent for all modern attempts to bring war criminals to justice, people like Milosevic and Karadic and those who oversaw genocide in Rwanda. But, I had never heard of the Neuengamme trial, let alone appreciated that the British had been responsible for it. Fourteen SS personnel, including the camp commandant Max Pauly, doctors responsible for experimenting with TB on children, and a guard whose duty was to kill those unfit to work by injecting them with phenol, had been tried, convicted, and eleven sentenced to death in May 1946 just at the moment when Goering and the others were defending themselves at Nuremberg.

Neuengamme trial

After I returned from Germany, I was intrigued enough by what I’d found to begin a long investigation into the British led trials after the end of the war. I wanted to know what had happened and why so little was known about them and what they had to say about the quality of justice meted out against the Nazis. I wanted to find out too how those thousands of camp inmates had died on 3rd May 1945, just a couple of days before the end of hostilities.

Over the next few years I came to realise how much had been forgotten when Nuremberg was remembered.

It took some years after the beginning of the Second World War for the Allies to think about retribution.

Though stories of massacre and war crimes were widely known and widely reported, though the Nazi persecution of the Jews had never been hidden, it was only when the tide of the war began to turn in the Allies’ favour did the rhetoric of punishment of the Nazi leadership take hold. Most of the impetus for justice at war’s end was prompted by the exiled governments of occupied Europe, the Poles and the Czechs in particular. They kept informing the British and Americans of the scale of killing happening in their homelands, though with little reaction.

In 1943 the US, Britain and the USSR eventually took notice and publicly declared at the Moscow Conference that there would be a reckoning. Not just against Hitler and his cronies but against every person responsible for committing a war crime no matter how minor. When victory became assured in early 1945 that promise had to be kept particularly when horrific films of the liberated concentration camps and their victims were shown to a shocked public.

After much negotiation, with the British keen on summary execution and the Americans and Russians insistent on a process of public trials, it was agreed to pursue the Nazis by judicial means. There would be two, complementary, procedures: trials of ‘major’ war criminals (the leaders of the Nazi regime like Herman Goering and Rudolf Hess) were to be held in Nuremberg whilst at the same time local courts martial of ‘minor’ war criminals would be delivered separately by the Allies in their particular territories. All those Germans responsible for committing war crimes, whether ordering them or carrying them out, were to be investigated and subjected to a ‘fair trial’ once the evidence was obtained.

Though the four main powers (Britain, USA, USSR and France) were to share responsibility for the Nuremberg process, the minor war criminals were to be pursued by individual states mostly where the crimes had been committed. Poland and Czechoslovakia embarked on a large programme of prosecutions that dealt with collaborators as well as German SS and army personnel and many other previously occupied countries did the same.

As for the British army, it took charge of hunting down and prosecuting suspects in North Eastern Germany, their zone of occupation. Prompted principally by the discovery of the terrible conditions in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, a War Crimes unit was hastily formed and sent out to Germany.

Thousands of SS members and camp guards were rounded up and imprisoned (often in the liberated concentration camps) whilst investigations into their individual guilt were supposed to be conducted. The British alone had 53,000 in custody by January 1946.

But the handful of investigators and prosecutors assigned by the War Office in London were quickly overwhelmed by the task facing them. They were given insufficient resources to undertake the job properly. Lt Col Leo Genn, the officer commanding the No.1 War Crimes Team assigned to investigate the Bergen-Belsen associated atrocities, said he needed twenty times the personnel to interview witnesses, identify the SS members most culpable and prepare the evidence against them, always bearing in mind that they were bound by the principle that guilt had to be proven beyond reasonable doubt. That was a picture repeated for both the British and American teams across Europe. One American news agency reported in August 1945 that the US units were ‘swamped with pending cases’ and that the investigators were so few in number that they were looking ‘forward to almost lifetime jobs simply gathering evidence’.

The trial was ‘fair’ but for the victims it was a travesty

By the time the first cases came to trial, months before Nuremberg began, the British government had already started to lose its enthusiasm for the retribution planned. The Bergen-Belsen trial was hastily put together and was widely condemned for the sluggishness of its proceedings. It took several weeks to reach a conclusion. And even then, a number of SS guards accused were acquitted because of insufficient evidence produced against them. That may have supported the contention that the trial was ‘fair’ but for the victims it was a travesty.

From that moment, the British focused most of their efforts on cases of crimes against their own personnel: service men and women who had been executed or ill-treated by the Germans when captured. Though other concentration camp trials were pursued (notably Neuengamme and Ravensbruck) they attracted little if any public or media interest. Neuengamme, which was concerned with a litany of terrible crimes and the killing of tens of thousands of inmates, barely registered with the press. I found only one report of a few paragraphs in the Times and the Guardian.

The government also began to apply considerable pressure on the investigating teams to finish their work quickly. As early as the autumn of 1945 they were instructed by Sir Hartley Shawcross, the Attorney General, to complete 500 prosecutions by April 1946. It was an arbitrary figure and never achieved in the remainder of the War Crimes unit’s existence (less than three hundred cases were brought involving 900 accused of whom 250 were acquitted). But the demand encouraged minor crimes, which could be easily prosecuted, to be given preference. Gustave Klever, a junior German naval officer, was a case in point.

Klever was 45 years old and stationed in the small port of Cuxhaven, on the northern coast of Lower Saxony, for most of the War. His job was to issue clothing as quartermaster to the garrison there. When the British came in 1945 he wasn’t interned but instead taken on by the occupying forces to help with distributing food and clothing to the many refugees who’d ended up in the town. But after a few weeks a report was passed to the War Crimes Investigating Team alleging that he’d deprived unidentified allied prisoners of war of American Red Cross parcels at the end of April 1945. In fact, he’d been called to deal with a train load of these parcels that had become stuck at a railway station close by. The authorities were worried that the parcels were being pilfered from the wagons. Klever sent most to a nearby POW camp and the remainder (which wouldn’t fit on the trucks) he said should be distributed amongst German refugees from the fighting in the east. This was his crime.

Was this a war crime?

“At the end of April 1945 Germany was facing total defeat. Conditions were chaotic. The accused was a subordinate officer. He arranged for the parcels to be put in safe custody … Was this a war crime?” the British officer defending Klever asked. The court convicted Klever regardless, sentenced him to a year in prison and ordered that he be registered as a war criminal. It seemed absurd, even if it contributed to fulfilling the intention to pursue every person suspected of war crimes however minor.

I found many cases like this. They couldn’t help but dilute the effort to achieve accountability for all the Nazi atrocities. It made me wonder how many escaped justice for want of a sustained determination to seek out and punish those involved in the whole concentration camp network, those involved in perpetrating the Holocaust, those SS members, soldiers and civilians who contributed to the Nazi system of oppression and abuse.

As I delved deeper, it became clear to me that Nuremberg, however vital it was as a precedent, had sucked up the greater degree of retributive intent. And by doing so, it drew attention away from the hundreds of thousands culpable for crimes instituted by the Nazi regime both in the hundreds of concentration camps stretched across Europe and in every occupied country. By 1948 public concern for the whole enterprise was so minimal that the British and Americans in particular were content to draw a line. Over the next few years, those who’d been punished by long imprisonment were mostly released. They were allowed back into German society as part of a political settlement. Though prosecutions of concentration camp personnel would continue sporadically around Europe over the following decades, they were tiny in comparison to those who were known to be culpable.

The myth of Nuremberg as a virtuous endeavour remains strong. There is much to support it.

But for me it only makes sense when read in context: the stories of the perpetrators of atrocity and their investigators and prosecutors and judges provide a much more accurate picture of what was achieved and what failed. That was my intention in writing A Passing Fury. I found some unpalatable truths along the way.

One of the worst perhaps was the truth of what had happened to the 7000 inmates of Neuengamme. Evacuated from the camp by the SS as the Allied forces approached, they were transported to Neustadt Bay and packed into three ocean liners. A Red Cross official in the area was told and immediately informed British intelligence officers that the ships contained concentration camp prisoners. The information wasn’t forwarded. On 3rd May 1945 a squadron of RAF Typhoon fighter bombers attacked the ships destroying each one. The few survivors who managed to jump overboard were reportedly strafed in the water. Many others were executed by local SS and other personnel when they struggled ashore.

No one was held responsible for this tragedy. It didn’t register as an atrocity. Neither Nuremberg nor the whole panoply of trials undertaken by the Allies would address it.

Photo by Andrew Williams