This memoir from a summer spent in Palestine explores the existence and resistance of communities living in the shadow of the Separation Wall. Undergraduate Law student Jaskiran Sandhu wrote this story as the joint-winning response to the annual Lacuna Writing Competition.

Last summer, I saw a revolution on a wall.

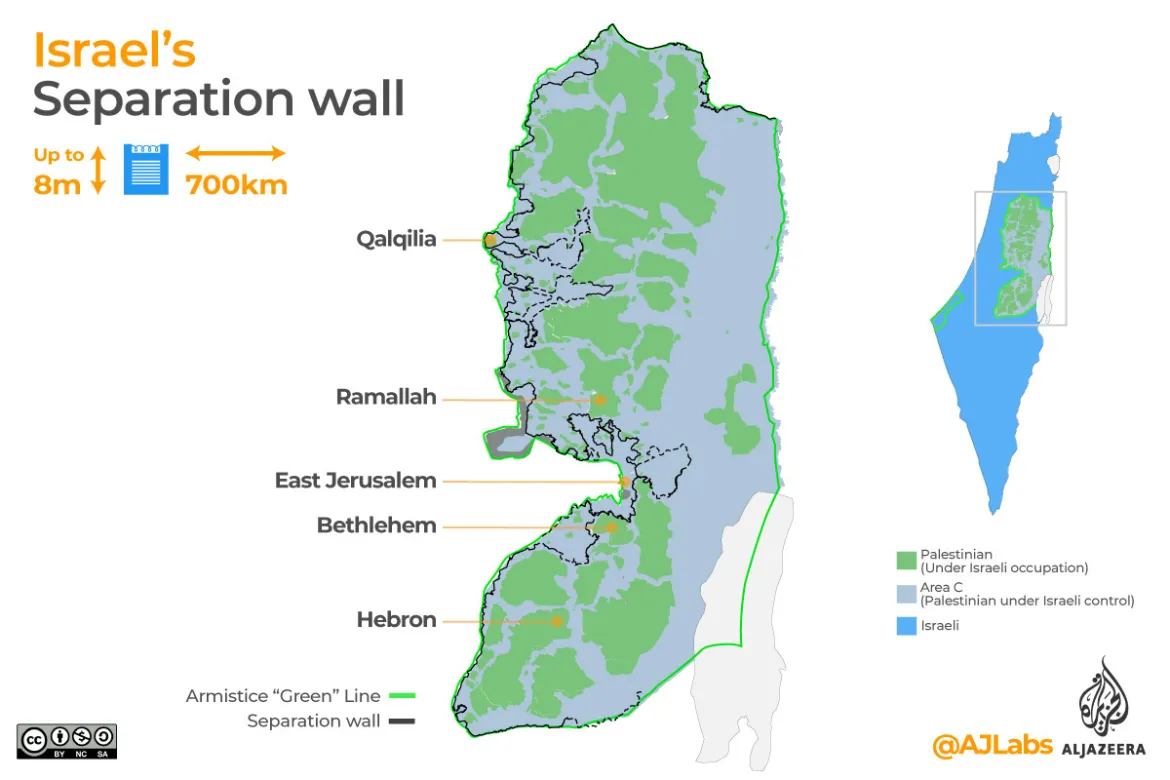

‘The barrier’ stood like a juggernaut, splitting the soil below. Israel’s separation wall, declared illegal by the International Court of Justice, does not run along the recognised ‘Green Line’ between Israel and the West Bank & East Jerusalem. It is built as deep as 22km (13 miles) into Palestinian territory in some sections; splitting communities in half and leaving farmers reliant on Israeli permits to access their own land.

About 85% of the wall falls within the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Once completed, the wall will be more than double the length of the 340km (211 miles) -long Green Line. As a result, the barrier has created a permit regime that has restricted the freedom of movement of Palestinians since 1967 and laid the groundwork for the de facto annexation of the West Bank.

Israel’s separation wall and the Green Line compared – Source: Al-Jazeera

It’s the beginning of August 2023 and I arrive at Ben Gurion Airport in Tel-Aviv in the sweltering midday heat. I am to make the journey from Tel-Aviv to Damascus Gate and eventually to Al-Khalil (الخليل) (Hebron) in the West Bank.

The words of my friends and family ring through my ears, words of warning and fear of “risking my life and going somewhere so dangerous”, as they put it. But at twenty years old, I am as stubborn and determined as I was at five. I am here for a legal internship and to learn Arabic with ‘The Excellence Centre’ in Al-Khalil.

I am here to learn about a part of the world that is very different from my own. I am here to listen to those stories that they don’t publish in the media.

My journey didn’t begin at the airport. It began sitting in a cafe, reading the same book as a woman with big, brunette curls sitting opposite me. As soon as we realised we were somehow in the same place, reading a not-so-trendy book at the same time, we became friends.

This book was “Mornings in Jenin” by Susan Abulhawa. And this friend became not only someone to go through the book’s heart-wrenching story with, but also someone who shared my interest in Palestine and its people’s history of suffering.

Albuhawa’s narrative, originating from the days of The Nakba (النكبة) – the Arabic word for ‘catastrophe’ – explores the perspectives of three generations of a family displaced to the refugee camp in Jenin, where the history began to take physical form and resonate with my heart. The book is a raw, powerful illustration of the human costs of the displacement and injustices the Palestinian people continue to face.

Photo via Northern Lights 119

I began my search to educate and immerse myself deeper – believing that the most authentic and personal way to learn is to experience first-hand. As a law student, I wish to understand the legal and human rights context in every situation, and the legal internship at The Excellence Centre allowed me to combine these intentions.

Jaskiran’s host family and volunteers playing Uno in their garden

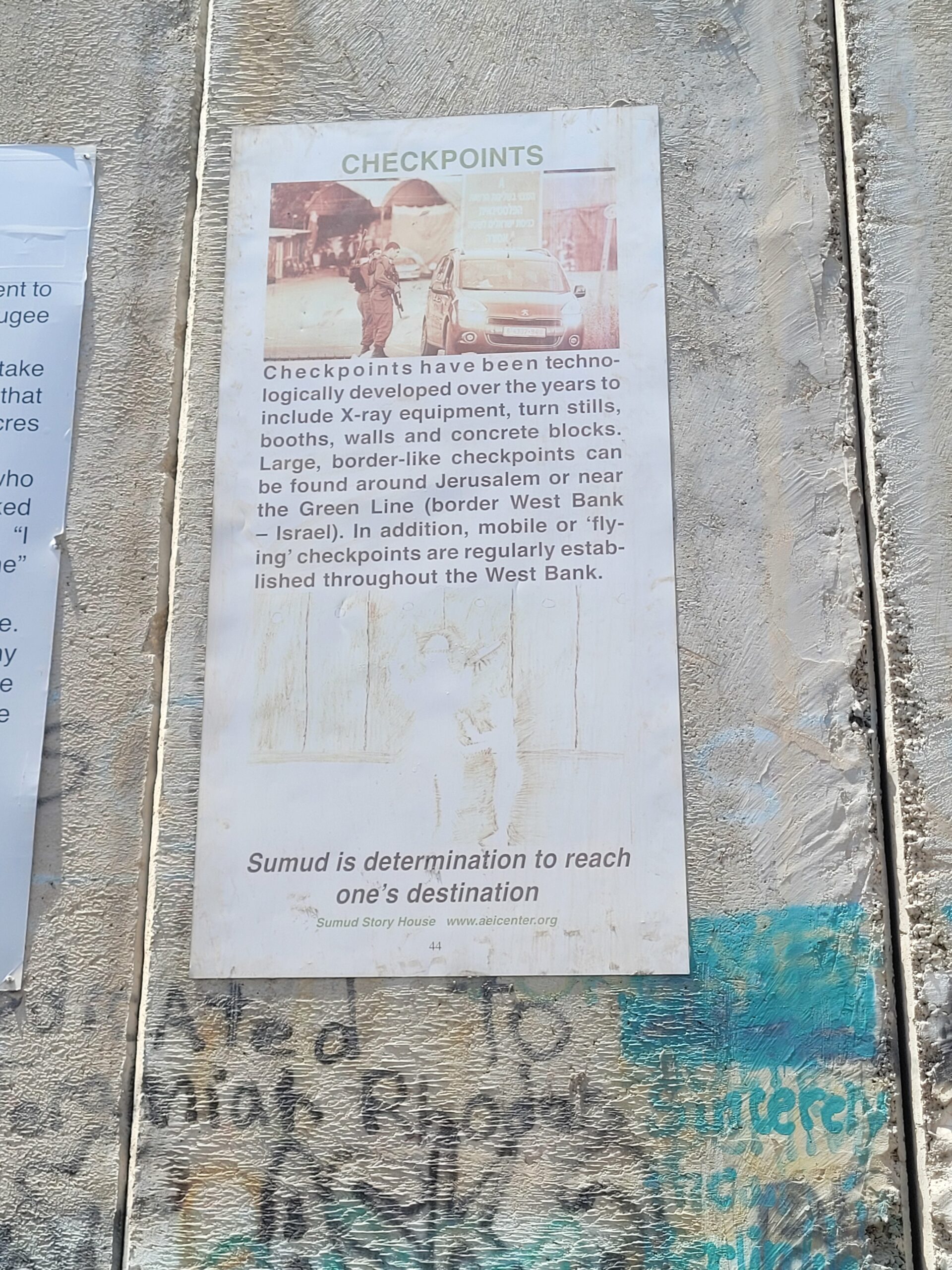

It takes me almost five hours to reach the Centre, due to multiple checkpoints and three different vehicle changes because of significant safety restrictions advising Israeli citizens and tourists alike against crossing into Palestinian territory, “for your own safety”.

The Palestinian number-plated sherut (shared taxi) is to drive me from Damascus Gate to Hebron and the further we drive away from Israeli territory, the more ubiquitous walls and barriers become, until we are driving on a highway that is split down the middle by a wall, Palestinian cars on one side and Israeli on the other.

There are other walls on the side of highways and roads too, blocking access to that land. I consider them innocent enough; to stop cars driving into fields or communities of houses built nearby. Later in my trip, I learn that all those white houses lining the highways into the West Bank are Israeli settlements, built on top of the ruins of Palestinian communities that were displaced and removed.

Israeli settlements along the route from Damascus Gate to Hebron

On day trips with other volunteers from the Centre, we pass through the best-known of all Israeli checkpoints more times than I remember: the Rachel’s Tomb crossing into Jerusalem from Bethlehem. Bethlehem is “Area A” under the Oslo Accords – under the full civil and security control of the Palestinian Authority. It is more a border crossing than a checkpoint.

Our sherut driver drops us outside the opening of the metal revolving doors, restricted from going any further because his number plate says “P” for Palestine. He’s been telling us stories of his children and his home in Bethlehem; how he’d like to visit Jerusalem with them some day. We see taxis and cars marked “IL”, for Israel, speed past us.

On foot from here, through the revolving doors, the inside terrifies me. Everything is metal, the walls, the ceiling, the doors, even the security boxes that blue and white uniformed soldiers sit in, their M16s resting beside them.

No words are spoken between us, but a quick look at our British, American, and European passports separates us to a line at the furthest end of a long row of blockades inside the Rachel’s Tomb crossing.

The lone Palestinian woman to our left shoots us a quick glance, as I remember yesterday’s visit to a hospital in the West Bank. One of the doctors explained how some of their staff have to travel to Jerusalem for training and sometimes patients who cannot be treated in Hebron need to be transported for treatment in Jerusalem. Everyone who travels into Israel proper from the West Bank must acquire a signed and stamped permit from the Israeli government, which can take anywhere from days to months and includes extensive background checks, including that of your father and grandfather.

Even after all this, the soldiers at the crossing may still refuse you at their discretion.

At Tel-Aviv Airport, on my way home to the UK, I will be questioned extensively by an Israeli security officer, asking where my surname comes from, where my father and grandfather were born and any countries they lived in throughout their life, whether I have any Palestinian relatives or friends and the names of the people I met on my trip. To protect those I met, I will have already prepared for these questions with fake names of friends and a fake itinerary of the most popular Israeli tourist hotspots I supposedly visited; all the bars I frequented on my month-long trip and how fun swimming in the Dead Sea was. But my words will come out shaky and breathless.

She will see right through me. I will be separated and have my bag searched and my Palestinian souvenirs will be considered too ‘provocative’- a keffiyeh, a poster of the olive fields, a report on the state of human rights protection and violation in the West Bank by the International Commission for Human Rights in Ramallah – and confiscated. The only souvenirs I will bring back are little coffee cups, a glass-blown ornament, and a few earrings.

Back at Rachel’s Tomb crossing, our passports and our temporary visas are scanned and the barricades are opened. We walk out into Jerusalem on the other side of this metal labyrinth, the Palestinian woman is still standing, waiting to be let in.

Read more: Life in occupied Palestine

Two weeks into my trip, I’ve been a few times now to Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus and home to the Church of Nativity and a population of Christian Arabs. This is where I meet the barrier up-close for the first time.

Revolution and resistance are sprawled across its concrete, from quotes to larger-than-life murals of Nelson Mandela, Iyad al-Hallaq and an Israeli soldier with a KKK hood. This is a ‘wall museum’. The art spans decades of lessons learnt and forgotten about human rights and cycles of oppression and resistance.

Photo via FOR-USA Fellowship of Reconciliation

The wall grows taller and draws in closer the longer I look at it. Maha Saca, the Director of the Palestinian Heritage Center in Bethlehem, tells us stories of her childhood home that they left behind in East Jerusalem when the wall’s construction began in 2002. The Palestinians living in their homes for generations were ousted when Israel annexed East Jerusalem in 1967, being replaced by Israeli settlers. Today, over 700,000 Israeli settlers are living illegally (according to the UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights) in the occupied West Bank.

Maha Saca shows us wedding pictures spanning seven generations of her family: “How can they say this is a land without people for a people without land?” she asks us.

Photo via Northern Lights 119

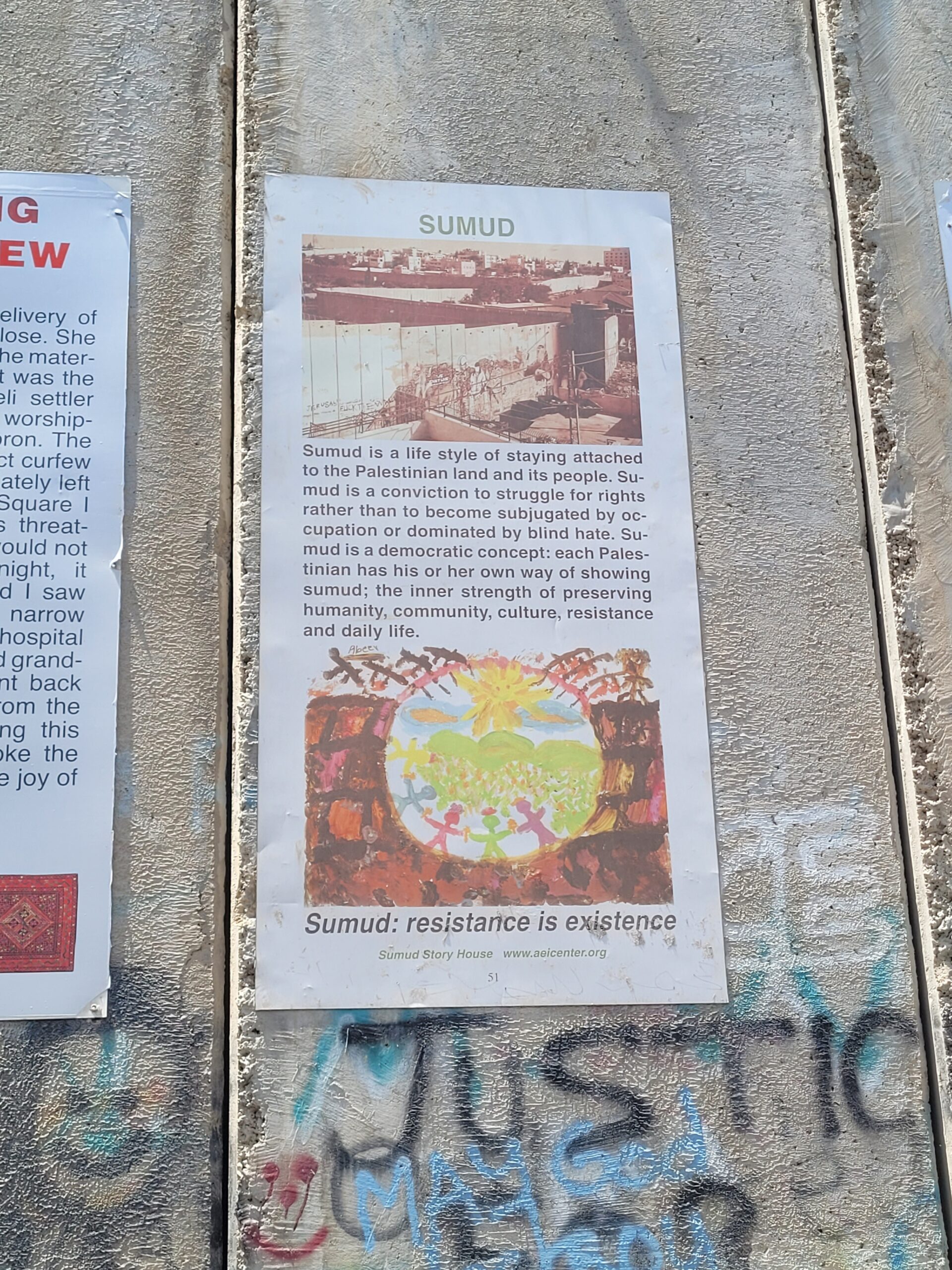

But this was no “land without a people”. Those I met in Al-Khalil and throughout my travels in the West Bank became so closely held to my heart because they were some of the kindest, most generous, most interesting people I’d known in my lifetime.

This is the influence of a people so willing to invite you into their homes for qahwa (coffee) and tell their stories. Not just stories about life under occupation, but also love stories, marriage stories, how to take care of olive trees, why the Levant is the most beautiful place in the world, what school was like that day.

For people who have never experienced Palestine, it is hard to conceive of such stories amidst conflict and suffering. But the universal human experience of family, love, home and quiet joys prevails enduringly. And this is, perhaps, the Palestinian people’s strongest form of resistance: to live their lives in spite of occupation.

As I continue my walk along the wall, I come across a phrase graffitied high on the concrete: “I cannot believe what you say because I see what you do”.

This phrase frames James Baldwin’s seminal essay, ‘A Report from Occupied Territory’, on the segregated Harlem ghetto in 1960s New York. Baldwin describes how white policemen call African Americans “dogs and animals when I don’t see why we are the dogs and animals the way they are beating us.”

At the time of writing, Israel faces allegations at the International Court of Justice of committing genocide in Gaza. Israel’s Defense Minister, Yoav Gallant, has stated that: “We are fighting against human animals” as Israeli forces level hospitals, refugee camps, and residential buildings.

On another trip, we visit Fawaar Refugee camp, the southernmost camp in the West Bank. A man I meet there asks me, in perfectly spoken English, to describe to him the colour of the Mediterranean Sea.

I had been in Haifa just days ago – one of the most beautiful places to experience the Mediterranean. I tell him: cerulean under the blue sky, tangerine during sunset, cool beneath my feet, colours as if seen for the first time. He tells me how beautiful he finds the sea of his country, a sea he has never seen. He closes his eyes, his inner world rich in colour. He opens his eyes, tells me he’s a refugee, born and raised in the camp’s 0.27 square kilometres. The camp is under Israeli occupation, with a large watchtower and checkpoint at the entrance.

This man tells me that it is not the loss of land that destroys a person but the loss of their heart. Their heart, left behind in homes destroyed by that alien arm crane blitzing away brick-by-brick. He tells me he left his heart behind in the daughter he lost while trying to pull her out of the rubble after an Israeli attack on his village many years ago.

I sit in the back of our private taxi, crying as we leave. Our passports are checked and we are allowed to exit, whilst the people who shared their stories with us, wave us goodbye behind the barricades.

Graffiti mural of the crane Israel uses to demolish Palestinian houses, on a section of the separation wall, Bethlehem

Photographs used are by Jaskiran Sandhu unless otherwise stated.

Main image via Northern Lights 119.

Read more: