The April morning is unseasonably warm, so much so that I roll down the windows of the car and let the breeze flap. I cannot fail to notice that the land is disconcertingly flat. From the port at Dunkerque deep into the countryside there is barely a raised speck to navigate.

The scene plays out before us like an infant’s drawing: big blue sky above and scribbled green-brown earth below, square buildings wedged somewhere in between. I had almost hoped for something altogether greyer than this, at the very least had hoped to hear the clatter of raindrops on the soil while being thoroughly soaked to the skin. Anything I have ever seen of this place has been gleaned from monochrome photographs, dimmed by age. The blues and greens come as a surprise.

We drive roughly southeast passing a number of villages that seem to exist only as places to travel through: Les Moëres, Hondschoote, Roesbrugge-Haringe, no more than a handful of people in each. Between them, the road cuts through the ridge and furrow of spring fields. The wire strung from telegraph poles is a constant companion at the side of the road, falling and rising between each stanchion like breath. M reaches out her cupped hand and lets the air push at her palm, looks to me for approval. John Lee Hooker rasps from the stereo, Boom boom boom boom. In this sunlight I might well draw the car to a stop, wander out together to a copse set just back from the roadside, lay down amidst the soft earth and squander an hour or two there. Boom boom boom boom, I’m gonna shoot you right down, right offa your feet.

Someone approaches me from behind in a sleek car, suddenly a looming presence in my rear-view mirror, takes offence at my leisurely pace and swerves out to overtake me. In fairness, there is little danger: one can see for miles ahead that there is no oncoming traffic. And frankly, I am dreamily coasting along in a lost time. M is, too.

Antiques Brocante Decoration, a sign reads outside a large square building. We pull to a halt. Outside there are old cast iron radiators, rusted fixtures, chimineas, wooden barrels, bathtubs, tables, empty cable drums, work benches, all in various states of decay and left to the open air. It’s as though they have been washed up on the tide. Inside is a warren of darkened rooms, each containing shelf upon shelf of items: beer glasses, dining chairs, clocks, dressing tables, mirrors, vinyl records. M is delighted. Like a child, she weaves through the aisles, each time returning with some dusty relic in her hands. Look at this she says, beaming, holding a bell jar out before her. Then, a moment later, she presents a marbled mantelpiece clock. As it is, we take away nothing but the tang of dust in our nostrils.

With his satchel and shining morning face

My grandfather, never a seafaring man, often poured a mid-morning brandy and made claims of the sun having passed the yardarm as a defence. I follow suit, ordering beer at the stroke of eleven in café on the town square in Poperinge. The place is so neat, neither a brick nor a cobble out of place.

Opposite me, M wears sunglasses and shirtsleeves, smears sun cream into her arms. Little rivulets of water gather on the outside of our beer glasses. We could be anywhere. We then slow-step through the town in that stately, sloping way that must rile the locals.

Pop, as resident troops once called it, was one of only two towns in Belgium during the Great War not to have fallen into German hands. Instead it served as a strategic position for British troops just behind the front. The railway line from here towards Ypres was key to the eastward movement of ammunition (and the westward retrieval of casualties). So says a signboard by the entrance to the church. Turning back to the square, awash now with the sound of fountains and conversation, I catch a glimpse of it in Another Time, busily and urgently peopled, abuzz with hearsay. Someone running from one side to the other across the cobbles with important news typed out on foolscap.

On the outskirts, opposite a dog-grooming studio and sandwiched on all sides by houses, is a military cemetery. We should stop by, I say. And we do, slowly navigating our way through the headstones in that careful, reflective manner of walking reserved solely for graveyards. I note the closeness of dates between deaths. It is difficult to do more than this. I want to point out that it’s a beautiful cemetery, motioning to the stark whiteness of the stonework, the little pockets of bedding plants at the end of the rows. But I don’t. We pass a family, French I think, who search for a headstone with the aid of something written out on a slip of paper. M is ready to go now, but I continue to watch them a moment. The father crouches at the grave, resting his elbows upon his haunches, and then traces the inscription on the stone with his finger. The rest do the same.

I remember a set of grainy photographs of Ypres from a school textbook, taken sometime soon after the war, in which silhouetted figures clamber about amidst rubble. As we park up, I describe them to M as best I can. The pictures could easily be copied out by the young school-age reader with tracing paper and a dark pencil pressed firmly into it. The effect would be the same.

Ypres had been squarely in the line of the Germany offensive towards France. At the war’s end, only jagged fragments of masonry were left standing and the centrepiece of the town, the thirteenth century Cloth Hall, was reduced to nothing. But here is a town that looks like a perfect set of teeth: upright, well- spaced and clean. No messy bridges or in-fills. The Cloth Hall has been meticulously restored to its pre-war glory. No one seems to notice anything untoward.

On this afternoon, a cloudless April Tuesday, it seems to matter little anyway. It is strange but I still wish for a downpour. The town square is much like its equivalent in Poperinge, but larger, giving room enough for a steady flow of coaches and cars. We sit in red plastic chairs at its edge eating hot salted fries and sipping drinks. M shifts in her chair to meet the sunlight. I want to talk of the Cloth Hall, the puzzling anachronism of it, but I can’t find the right words. M, in any case, is taken by the fries and holds up each one before eating it, nodding her approval.

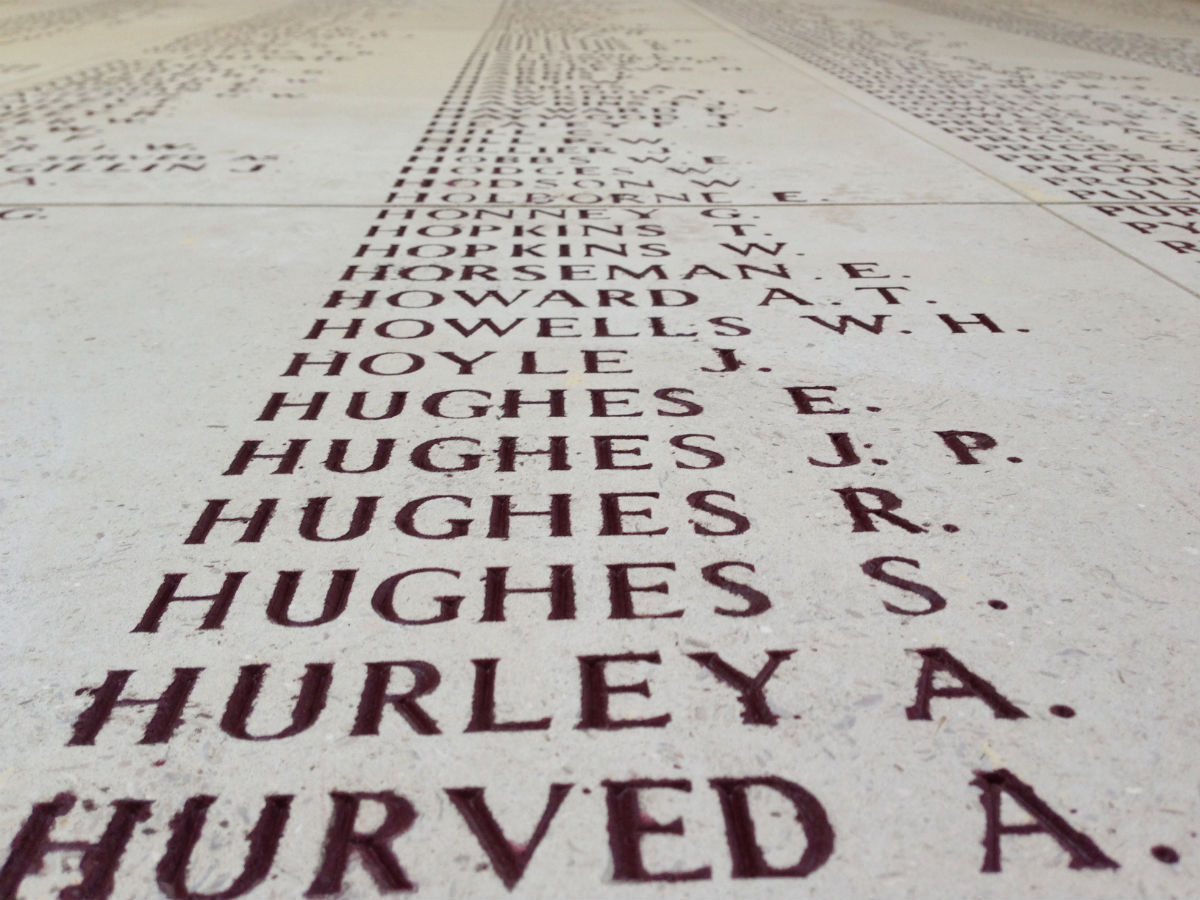

The chirpy chorus of the town square still rings in the ear when one walks eastward along Menenstraat toward the Menin Gate. The grand edifice of the memorial, though, with its clean arches and white stone steps, is a hushed and sober affair. People move around it reverently. Each evening at eight the Last Post is squeezed out on trumpets and it blows away the day’s gathered silences.

I can’t help but be struck by the way Ypres wears its history, less like a wound than an attraction.

I can’t help but be struck by the way Ypres wears it history, less like a wound than an attraction. Or, if that is too strong, then at the very least it is a town serving the purpose of remembering, like a mournful theme park. I am not disregarding the people who come here en masse, searching amid the thousands of engravings upon the bleached walls of the Gate, and whose photographs taken next to the names of loved ones will later sit on mantelpieces in Bolton, Adelaide and Toronto. I think only of how difficult it seems to reconcile the gloomy photographs from that school textbook – charcoal-grey scenes of ragged and stacked corpses, sodden rubble – with the carefully ordered catalogue of loss chipped neatly into polished stone.

Pointing to one of the panels of the memorial M gasps, says, Look, that must be three soldiers from the same family. Atkins, Atkins, Atkins. I can see it in her face that in that very moment she has become the grieving mother, Mrs Atkins. Her face is grave. I too feel the dull ache for the woman’s loss, but the punctuating click of camera lenses keeps bringing me back to the surface of the reverie.

By five, we are back on the road. I am tired, snap at M over something silly, and we drive for some time in silence. I play something doleful on the car stereo to make a point.

And then the lover, sighing like furnace

What a place to fall for. Kortrijk is a hodgepodge city of pre-war jewels and anonymous post-war tenements. Walking around its streets I cannot work the place out, cannot find a common thread to link one road to the next, and quickly give up trying. (Much later I think to myself, with hindsight: actually, is this not what I expected all along, a messy history like a cake badly iced, like something haemorrhaging unruly growths?)

I research before I arrive to see what role the city played in the war, for it is not a name that rings a bell for me. Nor does it seem to occupy a place in the canon, because its name, searched for online, brings up mostly postcard images of its high-sided city hall, and the pretty Broel Towers. (It is a useful experiment actually. Search instead for Ypres and one is greeted by a catalogue of dour-looking wartime images. It is like a ranking system for history.) In any case, I learn that an ungodly number of bombs were dropped on Kortrijk, not only in 1917, but again later. The new buildings that have sprung up turn their backs on what came before.

It is still balmy at seven when we head out. M has a thin cardigan draped over her shoulders and her hair tied up loosely. There is a funfair on the streets, and the city’s open spaces – Grotmarkt, Havermarkt and Stationsplein – are taken over by stalls and great towering rides. One, a large swinging pendulum flecked with bright lights, spans the width of the square in full flight, so that its riders must be able to peer in through the windows of the buildings at the edge. I wouldn’t know for sure, though, and don’t much fancy finding out.

There is too much merriment in the air to think deeply. There are dizzying rides and street vendors selling fresh donuts coated in sugar, for which people are queuing. M pulls at my sleeve to point out a dress in a shop window as we pass it. I pull at hers to keep on walking. After a while we wander lazily away from the centre, down Voorstraat and eventually into Begijnhofpark, where the sound of the fair is faint, almost lost on the breeze. We collapse to the ground like two teenagers, picking blades of grass from the earth. Lying on my back, M sat cross-legged at my side, I talk.

|| What’s your favourite painting? | I’m not sure. Why, what’s yours? | Renowned Orders of the Night. Anselm Kiefer | I don’t know it. What’s it like? |It’s wonderful. There’s a body laid out on the ground, prone, in the foreground. A man, facing upwards – he only takes up a tiny part of the whole frame – and above him it’s just darkness. Huge, black open space. And then amidst all this darkness there are thousands of stars in waves and clusters, picked out in white paint. The whole thing is textured, too, so everything leaps out from the canvas | Where did this all come from? | It just crossed my mind | Oh | Yes | I feel like I should know that about you | Know what? | Your favourite painting | Well, not necessarily. It’s not anything life-threatening. I bet there are things that I don’t know about you | Like what? | Try me | Do I have to? | Go on | Ok, what’s my favourite book? | Angela’s Ashes? | Yes | Bad example. Another | Film | Bicycle Thieves? |Yes | Another | Colour | Purple | Yes | More | See, you’re enjoying this too much. Month | August | Why? | I don’t know. Because of the unerring beauty of long English summer nights? | Ha, obviously. But more specifically? | Because you don’t have to work for the whole month | Exactly | Bloody teachers | Piss off ||

The sun has gone from the sky, taking the blueness with it.

|| It is ridiculous how much you remember, sometimes | People generally, or me in particular? | You | How so? | You remember details that there is really no point in remembering | I don’t choose to | I know | Like what, though? | What’s that thing you do with the old Notts County team? | Which one? | You know exactly what I’m talking about | Division Two Play-Off Final? Wembley. June, 1991? First game I ever went to | Yes, I know. Go on, do it. I know you want to | What? | Just do it | OK, but only since you asked. Cherry, Palmer, Paris, Short, Yates, O’Riordan, Thomas, Turner… Regis, Draper… Draper… Draper – | Maybe I spoke too soon | Wait, Draper and… | Oh, come on. You got ten out of eleven. That’s already a little odd. Anyway, the point is that you remember things like that | That will annoy me now | I just remember things I’d rather not and don’t remember the things I wish I did | What things do you wish you didn’t remember? | I’m sure you know | No, I don’t. What are you talking about? | Oh, come on | What? I don’t know what you mean | Please don’t make me | M, tell me ||

Photo by Andrew Nash

There is a strange cocktail in the air of faintly pulsating fairground music and church bells. I make it eight. Someone’s soles scrape the path and we both look around to see a lady walking a tiny dog. M smiles fleetingly and then her face is serious again.

|| This is precisely what I mean, though. Look how you happily reel off lists of useless information – football teams and song lyrics and lines from poems – and yet at the same time you can seemingly wilfully forget something when it’s painful | But I don’t know what the thing is that I’m wilfully forgetting | Oh come on, it was a whole year of misery for me and you’ve conveniently forgotten | Oh, right. Let’s not talk about that now. I haven’t forgotten, of course I haven’t forgotten, but – | But what? It’s just easier not to think about it, you mean | Well, yes, I suppose it is | But for me it doesn’t ever go away | No, no, I know. I’m not suggesting that. It’s there for me, too, obviously | Not in the same way | No, of course not. Not in the same way, but it’s still there |Where, though? | What do you mean? | I mean, where is the memory of it? Because it’s clearly somewhere hidden away | I don’t know. Perhaps it’s screwed up like a piece of paper into a ball somewhere and tucked away, yes | How convenient for you | M, please. What am I meant to do with it? | Well, sticking with your neat little metaphor for a moment, I think you should keep it out on your desk and read it every day to remember what you did | Oh come on, what would be the point of that? | Then you wouldn’t forget how it feels. You shouldn’t be able to screw it up. I can’t do that | But I’m not proud of it. I don’t see why I’d want to keep looking at it | Because that’s exactly what I have to do. And for me it’s not some shitty little piece of paper that I can just fold away. The memory of it is like, I don’t know, like some big heavy coat that I have to wear all the time, just constantly weighing me down. It’s piss-wet through and all I want is to take it off and put on something dry but I can’t | You can | No, I can’t. Don’t tell me that I can because I can’t. I can’t | Well, I don’t know what to say | Good ||

Wild screams ring out in waves. The bright light of the rides hangs cloudlike above the rooftops. There is suddenly a chill in the air and M holds herself. The quarter-past bells ring.

|| And how would you like it to be? | What do you mean? | Memory. If not the coat, then what? | I don’t know | Well, try | I suppose, if it’s not possible that I can just burn it and forget about it | You can’t | Well, perhaps some sort of briefcase would be nice. You know, something I can lock up and open only when I absolutely need to | Nice | Thanks ||

A cyclist slides by, talking on a mobile phone.

|| I remember having a briefcase when I was young. Mum brought it back from work for me. Someone was throwing it out in the office and she knew I’d get hours of fun from it. Just filling it up with things I found around the house. I must have been – let’s see – about three or four – | Yes, well you would bloody remember that, wouldn’t you | Touché ||

M smiles. Suddenly the ground is uncomfortable, dewy on our backsides.

|| Come on, let’s go. Do you fancy some donuts on the way back? | Who’s paying? | Have a guess | OK, then | Hey, they were some good analogies | I know. Coat, wet through | Yes, coat – excellent. Speaking of which, put yours on. It’s getting cold ||

We walk back into town, buy a paper packet of donuts. I am soon covered in sugar.

|| Johnson! | What? | Tommy Johnson | What on earth are you talking about? | Cherry, Palmer, Paris, Short, Yates, O’Riordan, Thomas, Turner, Regis, Draper and Johnson. I knew it was in there somewhere. Just had to unlock the briefcase! | You’re silly | I know | And you’re covered in sugar | I know that, too ||

Telling M to go on ahead when we reach the hotel, I buy two bottles of beer at the bar. The young man who serves me is friendly, asking me where I come from, why I’m here. I wouldn’t mind knowing the same about him. Ten minutes of conversation pass and, when I finally reach the room, M has taken to the bed and is sound asleep. I run the water in the bathtub hot and deep so that it mists at the surface. The two beers are strong and make me feel heady. Slipping beneath the waterline, I smirk. I know how it feels to be piss-wet through. But I quite like it.

Full of strange oaths

An all-grey morning sky, like a dustsheet laid out. The road from Moorslede reaches Passchendaele and turns ninety degrees left, southward, towards Zonnebeke. For some reason, we do not stop in Passchendaele, instead continuing down the hill before turning off right to Tyne Cot.

It is an oddly placed thing, the cemetery, sitting halfway up a gentle slope. Tucked away behind hedgerows amidst tended fields, it seems a strange setting in which to hear the steady grumble of coach engines.

We stand by the gravestone of Private W. Lucas of the Leicestershire Regiment, killed in action in September 1917. M believes it to be the resting place of her great-Uncle, William. There had been a database of all Commonwealth war casualties displayed on a little monitor in the visitor centre, into which M entered the details she remembered. Four matches had been found, one of which was right here at Tyne Cot.

I feel sick, that sort of hollow-belly sickness where nothing would come up even if I tried. It is not the vastness of the cemetery that gets me, nor the relentless list of names of the dead that poured from a loudspeaker in the visitor centre. That was something altogether different, back there. Then, a group had streamed into the room and filled it with the sound of footsteps and voices. I was standing by a wide window looking out over the fields. There had been an accompanying key printed strategically on the glass, which marked out points of interest among what was once a battle site. History, signposted. But it was difficult to mourn publicly.

It is not the vastness of the cemetery that gets me, nor the relentless list of names of the dead that poured from a loudspeaker in the visitor centre.

No, the sickness came later, in a moment of quietude as we were walking down a gentle hill outside the cemetery walls, when the breeze briefly muted the voices of those inside. I felt like I was walking on sacred earth. Perhaps it had something to do with the lay of the land. A car had driven past and then slipped out of sight behind a tiny knoll in the landscape, taking with it the sound of its motor. Such was the course of the road, the car did not return to sight until it emerged out of the shelter of the little hill a mile or so away. I thought again of Another Time, and of all that could have once lurked in the shadow cast by this slight ridge. Men poised on their bellies, maybe, their voices lost on the wind, all of them waiting for the instruction to stream forth.

Between there and here is now just carefully tilled farmer’s land. This year’s crops are yet to show. I had an urge to pick up a handful of earth and throw it at the air. M watched me do it without saying a word.

We finally enter the cemetery itself and find the grave of Private Lucas using the coordinates issued by the computer. While M dusts dried leaves from the shoulders of the stone, I straighten a miniature wooden cross that has been wedged into the soil. Someone has been here before. We both crouch and take a moment. Not ever having known Private Lucas does not seem to matter. I graze my fingers across the inset lettering, before standing back and reading the inscription once more. M takes a tissue, wets it, wipes the shoulders of the stone.

The graves of Tyne Cot cemetery. Photo by Ben Sutherland

Back in the car, she telephones her mother, struggling to hear at first over the roar of a coach that lurches past the passenger window. No one could begrudge the enthusiasm in M’s voice, given the serendipity of the discovery. After all, this was an accidental pilgrimage. After a short conversation, of which I can understand little from the driver’s seat – uh huh, oh right, yes, oh, well we thought, yes we will, OK bye – she turns off the phone.

It turns out that we had been wrong. William Lucas went by the name James, did not fight in the Leicestershire Regiment at all – even if it was his home county – and was buried somewhere in the Netherlands. Our act of remembrance was misdirected. Our great-Uncle was taken from us as quickly as we found him.

With eyes severe

There are times when one reaches a fork in the road and there is no way of telling the correct route from the wrong one. Not metaphorically: very literally. M was adamant, tilting her head in tune with the map as the car approached a junction: the right way – the correct way – was off to the left. The classic farce followed, in which lefts and rights were pondered for so long that the result was a near collision with a tumbledown barn stacked with hay bales.

We might have laughed at the incident. Twenty minutes later we sit in silence and M has dark make-up smears across her cheekbones. I have squeezed the car keys so tightly in the palm of my hand that a little rivulet of blood has drawn. The only sounds are our breathing and a clicking coming from beneath the bonnet. It turns out it was a left turn after all, and I have apologised. It is not only this that I am asking forgiveness for, but the other thing she seemingly cannot forgive. Both of us are inexplicably angry.

We are somewhere west of the N8 road between Ypres and Veurne up on the North Sea coast, outside an abbey that was hard work to find. The roads here are narrow, caked with dry manure, and largely unsignposted. M had read about a beer made here by monks, a brew revered across the region and beyond. During the war, the monks had gone on brewing in this shaded little spot, when other breweries had been forced to give up their metal vats to German soldiers. A heady mix of good beer and history: I had not needed any more convincing than that. But soon after I pull the car into a parking space in the abbey grounds, feeling relieved to have finally located it, the two of us are arguing in a way that later reminds me of a pan of milk suddenly boiling over.

|| You used to be such a sweet boy | Used to be? | Yes, before. I don’t think you’d ever speak to me in the way you do now | M | What? | I find this so hard to deal with, this prelapsarian idea that you have of me. And, for that matter, this idea that now everything I do is always just a consequence of something that happened in the past. After my bloody Fall. Surely it’s not as simple as that. I’m the same person | I still have that picture of you, from then. You look so young. You had greasy hair and you were scrawny, but you were so lovely. You would have done anything for me | Wait. This is my point: it’s a picture. You have a picture. You look at it and get nostalgic and yet I could have been horrible to you the moment just before it was taken. And right afterwards | How is that meant to help? | Yes, OK, good point. I just mean that, well, you know what I mean | OK | I just don’t think we need to do this again now. How are we going to resolve anything from here? I don’t even know how we got here | That’s because I had the map and you seemingly don’t know your left from your right | Oh come on, don’t be difficult. You know precisely what I mean | You shouted at me | Yes, because you weren’t listening | I was listening, but I was reading the map and concentrating | But I needed to know which way to go before I crashed into that fucking barn | Why are you getting so angry? | Because | Because what? | Because, whenever anything happens like this, it’s never just as simple as dealing with what’s there in front of us. You always see that I’m acting as a direct consequence of before | You are, in a way | No, this is about me snapping at you just now. It’s not about anything else | I disagree | What happened, M, isn’t some monument set in stone. It’s not the bloody Arc de Triomphe, all roads leading to one huge stone edifice. I hate this. It’s more nuanced than that, and you know it is. I can’t go back and do it differently | Exactly. It happened | Yes, but for you it’s so simple. You’ve built it into something hardened over time and now I have to live constantly with this simplified view of it all that I don’t entirely agree with | So it didn’t happen? | M, Let me finish. Yes, it did happen, but not like that. It wasn’t such a clear thing | It was clear. You le– | Stop it. Not every argument we have can end with those words. We have to stop that. Don’t misunderstand me, I don’t think we should forget it all and pretend it never happened, but we have to try and remember it in a healthier way | It’s just so easy for you to say all of this stuff to me, though. You can’t understand it from my point of view | I know. I genuinely wish I could, as silly as that sounds. But what do I do about that? It’s your memory. Equally, you can’t know what it’s like for me | I can guarantee it’s worse for me | That’s not what I’m fucking getting at | Keep your voice down | Well don’t do that, then | Keep it down, there are people around. You’re embarrassing me ||

I take the keys from the ignition with purpose, as though I know what I am to do next. Instead I unwittingly squeeze the metal stem of the key in my palm. M says nothing, stares into the middle distance. When our breath settles, the silence soon becomes oppressive and I am out the door walking away from the car before even I realise. M does not flinch. I turn off up a dead-straight gravel track that hugs the outermost boundary of the abbey. On either side are tall, thickly set trees with thorny shrubs growing at their ankles. Even the sound of my footsteps angers me. After a few minutes the path opens out onto a little circular clearing in the trees, in the middle of which is a row of low stone pews and a pulpit carved roughly into rock. On a makeshift altar are a handful of lit candles and a wizened portrait of Christ in a frame. I sit down on the cold stone pew and draw breath, face the altar table. Blood has mingled with sweat in my hand and there is nowhere to wipe it than on my trousers.

It’s not that I am oblivious to history. It’s just this tendency to gather it up like stray leaves, make neat piles of it and position them at arm’s length

|| It’s not that I am oblivious to history. It’s just this tendency to gather it up like stray leaves, make neat piles of it and position them at arm’s length – how then are we to get at it? We have been Midases of memory – not turning it to gold, but transforming it at a touch into cold grey colonnades and statuettes. Like great heaps of memory-leaves stacked high and bedaubed in neat stone. But if history is a pile of leaves, I want to kick my way through it, not bothering to look out for the dog shit and slugs bundled up within ||

I pull stones from the wet earth. Mud wedges beneath my fingernails. I face the trees and begin to hurl the stones one by one. Each time I miss the trunk I throw the next harder, the next harder still, until I am desperately flinging stones and am soon all but out of ammunition. I want to hear the echoing crack of stone against bark. I skip the low boundary fence and approach the nearest tree, striking it with the outer edge of my hands over and over. The rough bark makes an imprint in my skin. When there is nothing left in me I slump to the ground. There is only the sound of birds flapping like paper somewhere above.

|| Will we always be tied so tightly to the memory of it, so that one sharp yank on the leash takes us right back there? I don’t want to be set free of it. I just want perspective. What does it even mean to us right now? It’s something different than it was yesterday, certainly different to what it will be tomorrow. Give it a year, a decade – then what will it mean? Maybe one day I’ll miss its obdurate presence and will long for its return. ||

There are all manner of things growing here in this woodland. Little flourishes of poppies, buttercups and corncockles. Great knotty greenery all intertwined with itself. I pluck a poppy, dismantle it, scatter the parts around me. The red dye of the petal mixes with the blood and the mud and the bark. It will grow back next year, I think, that flower. It will look almost the same here, but not quite. My hands ache and they are filthy. A piercing pain begins to burn between my shoulder blades from the throwing.

|| I don’t blame her. I get it, I get that it hurts. I understand that it is big and immovable. And no one questions the finer workings of a millstone when it’s round his or her own neck. But – ||

Landscape of memory, Photo by monkeyinfez

Climbing to my feet, I brush myself down and return to the path. I look back to see the outline of my body in now flattened undergrowth. The pews and the pulpit are still visible in the clearing. Now two people are there, lighting more candles. I walk the opposite way. They must have passed by me while I was sitting there, without noticing. I did not see them either. We could not see the wood for the trees, I think, and then chuckle. Where’s M when you need her? And with that, I do begin to worry where she might be.

When I return to the car she is just as I left her. She asks what I have done to myself, for my shoulders have now seized up and I am somewhat soiled. My hands are red and brown. Reluctantly, I tell her about the stone throwing and describe the pain. Before I can ease myself into the driver’s seat she is up and out, gesturing for me to come to the back of the car. She pours water from a bottle onto my hands and washes some of the dirt away. Then, standing behind me, she places her hands on my shoulders, takes her mouth close to fleshy part between the blades and blows. The hot air seeps through my shirt, spreads across my whole back, and the pain eases slightly.

I thought you might have driven away and left me here, I say, only half joking. There is a pause. I considered it, M replies, but you had the keys. She makes as if to leave and I ask her about going to buy the beer that we have come for. It’s in the boot, she says.

A world too wide

Pull over here, M says, spotting an opportunity. A handmade sign hung from a tree by the roadside signals another brocante. We creep reverently up a dusty track, slow enough to announce ourselves.

An old man in a scruffy, buttoned shirt greets us warmly at the threshold of the property, points out three buildings for us to browse in Flemish. It seems all the world’s tat is gathered here. M is delighted. I think: Why have we stopped? We are unrelentingly gathering things up from this landscape to take home.

The first room is filled with teapots, dinner plates, jugs, candlesticks, vases and the like, the second with drill bits, stray castors, planting trays, rusted trowels and brackets. In the third, a tumbledown barn where light floods in like stars through holes in the roof, are countless old bicycles with flattened tyres, a lawnmower and some farming equipment. As we look around, the old man takes to his knees and lowers little plants into holes in the ground. He pats down the earth each time with the side of his hand. His dog joins him at his side, a lumbering old retriever who collapses and lolls out her tongue.

M is almost giddy – she shows signs of that phase that comes at the back end of tiredness, like gallows humour. She picks up item after item and comes to convince me of the need to purchase it. Crockery, decorative bowls, highball glasses, cracked serving dishes.

What an assemblage of items this is. Annexed and left to gather dust, there are things here that must tell a thousand tales. Cups that have been sipped from, bicycles once ridden. How exhausting it must be, I think, to keep them all here like this. He cannot sell many things – the dust gives this much away. Instead, I imagine his hoard becoming always larger, brown boxes of old goods left by passers-by at the gatepost. I imagine a wife, too, scolding him for this ever-growing compendium of junk. In this daydream I picture him, the old man, delicately placing each new item on a shelf, hoping for some chance customer to come and buy it so that he can grin teasingly at the wife, parading the money before her. But there is something about the careful way he has stacked the goods that also suggests he dreads the possibility of each purchase.

I look over to him, lifting little weeds from the soil. He wears a face at once pained and yet peaceful. The dog slaps her tail once or twice on the floor and a puff of dust rises.

We arrange our chosen goods on a table and the old man, creaking from his knees, comes to tot up. I watch the way he writes – slowly – gripping the pencil in his muddied hand, tapping it on the surface of each item as he goes along mumbling his calculations. We buy from him four gold-rimmed glasses, a stack of black crockery, a decanter, a set of teacups and, from the barn, a large metal ammunitions trunk. He packs the smaller items in old newspaper so slowly that I feel he might be about to change his mind and send us away empty handed. Everything is then placed within the trunk and together we ease it into the car. Lacking a common language, I shake the man’s hand – he offers a gentle bow to M – and we bid him farewell. The glossy look in his eyes confirms what I had thought: he wants rid of these items but cannot bear to see them go.

Driving down the track to the road and considering our haul, I notice that everything we have bought is a vessel. We have purchased only things designed to hold other things, and I find this unsettling. M cannot believe our luck. All that for less than twenty euros, she says, proudly.

Sans teeth, sans eyes

This landscape makes one weary after a time. I feel like even the car now labours along these flat roads, and then I realise that it probably does: we are much heavier on our way home. M half sleeps in the passenger seat. The smooth asphalt is kind to her, doesn’t deem it fit to nudge her awake.

There is a simpler route back to Dunkerque. One northward turn on the circular road at Ypres would have quickly delivered us to the main coastal route. But instead I wind through a host of small villages – Elvedinge, Boezinge, Longemarke-Poelkappelle, Vleteren, Proven. I loosely follow the arc of the sun westward and soon meet with a road I remember from before, ridge and furrow on either side. I put a disc into the stereo slot – Ocean Songs, by Dirty Three – and slide the volume up. Strings whine along track after track, accompanied by the laboured trundling of percussion. The Restless Waves, Backwards Voyager. M does not move.

When she finally does begin to stir, glancing from the window and licking her lips, I feel like she is gearing up to say something profound. Memory can both be kicked up like dirt and polished like brass, she will announce. The stories of those who came before are ours – yours and mine (said looking directly at me, then) – to claim as our own or to leave to the seasons. Or: we must remember to forget.

But she says, Let’s stop at a big supermarket and fill up on booze before we go back home. I laugh, change the disc, and clasp her forearm for a moment with my free hand. Big John Lee croaks, Let’s go out tonight, while the moon is shining bright. Absolutely, I say.

Photo by nataliej