I am English. Alan is Scottish. And during the course of our conversation, I am constantly reminded of what it means to live in two increasingly different social and political landscapes.

Professor Alan Miller is Chair of the Scottish Human Rights Commission, and so the most important human rights figure in Scotland. And when I listen to Alan talk, human rights do not sound like the marginalised political punch bag that they are south of the border where I live. Instead, human rights in Scotland seem integral to wider debates about Scottish independence, its changing identity as a country, and Scottish views on austerity and prosperity. And Scottish perspectives on all of these issues look very different from those I experience on a day-to-day basis in England.

Human Rights in Scotland, Human Rights in England

The attitude of the Westminster government looks deeply disturbing to a human rights advocate like Alan Miller:

“The toxicity of the rhetoric coming out of Westminster on a whole range of human rights questions is deeply worrying. For instance, you have attitudes that border on the xenophobic towards asylum seekers or towards those suspected of terrorist offences; seeking to have them deported without a great deal of regard to whether they will be subject to torture in countries they are sent to.”

In England, human rights do seem constantly under attack. When politicians talk about human rights it is usually in derogatory terms, from Michael Howard’s “avalanche of political correctness, costly litigation, feeble justice, and culture of compensation” to Jack Straw’s “villain’s charter’. The Conservatives want to repeal the Human Rights Act, and the other political parties appear reluctant to leap to its defence. Probably because a view has evolved over time, fuelled by a hostile press , that human rights protection works only for unpopular groups like criminals, foreigners, and ‘fat-cat’ lawyers.

In England, human rights do seem constantly under attack. When politicians talk about human rights it is usually in derogatory terms,

In Scotland, attitudes to human rights could not be more different. Politicians with human rights convictions feel comfortable putting them at the heart of their policymaking. Most notably, the Scottish Government states boldly in its campaign for independence that “[Our] vision is of a Scotland, fit for the 21st century and beyond, which is founded on the fundamental principles of equality and human rights…”

Alan sympathises with English human rights advocates, faced with such hostility:

“Sometimes it must be difficult for the human rights community within England, engaging with that Westminster bubble, to be ambitious and conviction-based in linking what human rights really mean to the real lives of real people and getting on the front foot in order to do that. But that really is a responsibility that all within the broader human rights community have, whether academics, practitioners, activists, because we have a shared responsibility in the UK to at least limit the damage being done at this present time.”

And one of the key areas where Alan can see damage being done to the lives of ordinary people is in some of the austerity measures being pursued by the UK government.

Differing Attitudes to Austerity: The Bedroom Tax

For Alan the ‘bedroom tax’ is the worst example of the failures by the Westminster government to take the human costs of austerity measures seriously.

The Bedroom Tax

Since 1 April 2013, welfare reforms have cut the amount of benefit that people receive if they are deemed to have a spare bedroom in their council or housing association home. The measure potentially applies to all housing benefit claimants of working age, and is commonly referred to as the ‘bedroom tax’, but also known as ‘size criteria’, ‘under-occupation penalty’ or ‘removal of the spare room subsidy’.

“It is a measure” he says, “that, in many instances, affects those sections of the community that are least well equipped to withstand its impacts. To these people, it will either cause them tremendous financial hardship or disruption to their personal and family lives and place in the community. And from any human point of view it is simply not a reasonable or proportionate way of making cuts in public expenditure. It just fails on all counts and is a dramatic example of what happens when no proper account is taken of human rights.”

Criticism of the bedroom tax is no longer a minority sport

Criticism of the bedroom tax is no longer a minority sport, even in England. Government claims that that the tax would free up under-occupied homes and reduce over-crowding look increasingly misplaced. A year on, figures suggest that just 6% of tenants have moved. Research shows that two-thirds of households affected by the bedroom tax have fallen into rent arrears, while one in seven families face losing their homes. Local governments are arguing that, with limited opportunities for tenants to downsize, they are having to step in to provide large amounts of support to households in financial hardship.

A recent report by the UK Parliament’s Work and Pensions Committee reinforced a view expressed by numerous other groups that it is the most vulnerable in society who are most affected by this measure, and it is those with disabilities who are suffering the greatest; Between 60-70% of those affected households in England and 80% in Scotland contain someone with a disability.

Some high profile cases have also emphasised the injustice of the measure; in October last year a Glasgow tribunal heard the case brought by a woman with a 3 square metre bedroom who has advanced multiple sclerosis, and sleeps in a hospital-style bed with a tracking hoist and a frame over her bed to assist her movement. She has an electric wheelchair parked beside her overnight. Her husband sleeps in a different room. And yet it was deemed surplus to requirements, a ‘spare’ bedroom. The judge in Glasgow ruled this breached her human rights.

The Conservative Party now stand alone in their defence of the bedroom tax. Even their coalition partners have withdrawn support, saying it has caused “huge social problems”. But in England, the political consensus on the tax only broke down very slowly. It took the Labour Party six months after the tax was introduced to voice opposition , and the Liberal Democrats waited a year. In Scotland, it has been a politically toxic issue from the start, and is a key symbolic issue in the campaign for an independent Scotland. Deputy First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, described it as “one of the worst policies introduced in Scotland since the poll tax.”

The human rights dimension of the debate appears to have played an important role in Scotland. One of the key events was the visit of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing. While the Westminster government were ridiculing and vilifying her investigation of the human rights impact of the bedroom tax, in Scotland, her findings were taken seriously, and became an important part of the wider political dialogue.

Alan explains her impact by saying “The visit of the UN Special Rapporteur was important in reinforcing the work already done by the Scottish Human Rights Commission. The UN Special Rapporteur saying ‘this is a breach of international human rights’ then became a very important public issue. And the introduction of a human rights dimension of it played in the public debate, and combined with the political opposition of the Scottish government and the constitutional discourse in Scotland around independence. And it became very powerful. It was a perfect storm. ”

It is of course difficult to verify the precise part that human rights discourse played north of the border in this complex political controversy. And as the chief advocate of human rights in Scotland, it is no surprise that Alan Miller is keen to emphasise their role. But there is ongoing evidence that human rights are a powerful consideration in the Scottish debate. The Scottish Parliament’s Welfare Reform Committee’s recent report into the impact of the bedroom tax starts in its very first paragraph with the assertion that the tax is “iniquitous and inhumane and may well breach tenants’ human rights.” The contrast with the approach in England couldn’t be more stark: a report written two months later by the Westminster Parliament’s Work and Pensions Committee, although deeply critical of the tax, makes no mention of the human rights dimension at all.

One has the feeling that human rights in Scotland are part of a potent social justice discourse that is largely absent from many equivalent debates in England. That isn’t to say that human rights are always popular north of the border. There were high levels of hostility in Scotland, for instance, to human rights arguments in favour of prisoners’ rights to vote just as there were in England.But human rights arguments do seem to resonate more strongly, and this is in part because there are real efforts to link human rights to the real lives of real people inScotland in broader public policy debates on issues like health and social care. Alan’s experiences have led him to believe passionately that human rights need to be at the centre of these kind of debates. And there are serious dangers when they are not.

The Deeper Dangers of Austerity Politics

The austerity politics of the UK Government may worry Alan, but he has a comparative experience that sends even more shudders down his spine. He is also Chair of the European Network of National Human Rights Institutes and so has regular discussions with his counterparts from 28 countries from across Europe. And from this experience he knows what happens when austerity bites in an even more extreme form than we are currently seeing in the UK:

“In Greece, we have seen the rise of extremism with Golden Dawn and an increase on attacks on foreigners. But why is support for parties like Golden Dawn increasing? It is because of the breakdown in social cohesion and the anti-Europe, anti-government anti-establishment sentiment that has understandably been felt by wide sections of the public, for whom society is no longer working.

If you have a society where people have no means of subsistence, where mothers can’t afford to pay to go into hospitals to have babies, that is not going to work.

“If you have a society where people have no means of subsistence, where mothers can’t afford to pay to go into hospitals to have babies, that is not going to work. And in its place, and in place of rule of law and social protection you have anarchy, you have lawlessness, and you will have resort to individuals and communities fending for themselves and it becomes the jungle. We should never be there, but that’s where we are.”

But, perhaps perversely, it is because of this dark place in which some countries now find themselves, that Alan perceives human rights being taken more seriously than they have been before by a range of important actors.

“Among the decision-makers and policy-makers at the highest level, the way this is beginning to come home to them is from a security point of view. What we are seeing in Greece for example is the rise of extremism, social cohesion being dramatically challenged. There is an inability to manage incoming migrants who are moving through economic pressures of their own, coming from North Africa and elsewhere. And there is now a recognition that human rights are part of the solution and prevention of these situations developing. And if for no other reason, that is why it is now entering discourse.”

So can human rights really play a serious role in actually preventing breakdowns in social order and community cohesion? Alan is quietly optimistic that they can.

A Vision of Prosperity: Moving Human Rights Upstream

Whether it is the imposition of the bedroom tax or an austerity programme in Greece leading to social disintegration, the need to think about how we can avoid such situations happening in the future appears uppermost in Alan’s mind. He argues that “we should have a governance framework where these kinds of policies never happen in the first place, and our society is managed, according to principles and values that prevent it.”

“There are a clear set of decisions that we have taken in the UK that have fuelled the human crisis that we are now seeing. First, some other countries do not have the same level of financial crisis because their financial sectors were much better regulated and so they didn’t provoke the same extent of financial crisis which we are suffering in the UK and in other countries. And then in identifying how to govern a country that is facing financial hardship, we need to look at it as a whole, from raising of tax, gathering revenue, to budgetary decisions about what should be the priorities for public spending. And throughout these processes priority should be given to the protection of those who are most vulnerable.”

For Alan, human rights can play an important part in this vision of governance. But he recognises that there is a need to move human rights ‘upstream’ if they are to play a serious role in these types of discussions: “Traditionally human rights have only entered the debate in terms of monitoring the impact [of spending cuts] and trying to provide a remedy to individuals. But we need to go to where these decisions and policies are made relating to budgetary decisions, tax revenue, tax collection, resource allocation and ensuring that right up the food chain, human rights are imbedded into key decision making processes. And it is not just among governments that this is necessary, but also among international financial institutions like the World Bank and the IMF.”

I ask Alan whether human rights, and human rights advocates, are really prepared to play this kind of role. And he admits that there is a need to develop new skills and approaches: “[They] have to step up and have to get out more and engage with other disciplines and expertise and enter into these arenas, so that human rights is not just in the court room, its also in boardrooms of organisations … But it would be a mistake not to go to the heart of the matter where human rights really are at stake, because many of the important decisions that are being made, are being made at a macro-economic level.”

For an Englishman who is used to politicians lining up to bash human rights and debates about whether to repeal our national human rights law, this all seems rather fanciful. It seems impossible that politicians would allow human rights to play a part in actually steering the way a country is governed. But Scotland is a very different political landscape, and it has just produced its first National Action Plan for Human Rights (SNAP).

Alan explains that “at its heart [SNAP] is a commitment from very wide parts of Scottish society including government, civil society, and public authorities to apply a human rights based approach through all of governance and decision making in Scotland. It’s a very pragmatic roadmap for the progressive realisation of internationally recognised human rights and a process of collaborative implementation and independent monitoring. There will be annual reports to parliament, there will be indicators developed. It will be overseen by the former Auditor General of Scotland.”

Alan sees SNAP as having a potentially far-reaching effect “Human rights need to be integrated at all levels of decision-making and people need to be empowered to better understand and affirm their rights in their interactions with public authorities, whether its health boards, or the care sector. Policy-makers and decision-makers at a local and national level, need to see themselves as much more accountable to those to whom they provide services.”

“Human rights need to be integrated right up to the decisions being made about the annual budgets, allocation of resources, and the national performance framework. What are the priorities, what are the measurement indicators that Scotland should be ensuring to capture the country’s progress? And we will be linking all that into the universal periodic review process of the United Nations where Scotland will open itself up to being measured in terms of what progress it is making in terms of that roadmap.”

This is bringing human rights ‘upstream’ from the river estuary to the mountain spring. Of course, much depends on the practice that actually develops. Will the commitment from the Scottish Government to SNAP translate into real commitment, new decision-making processes, and improved human rights outcomes for the people of Scotland? Will the spring water remain pure when it flows into murky political processes, fiscal fights and bargaining with vested interests? But, the vision offered for the role human rights might play is extraordinary. And it could not be more different from human rights in England, still flailing around in the estuary, trying to avoid being washed out to sea.

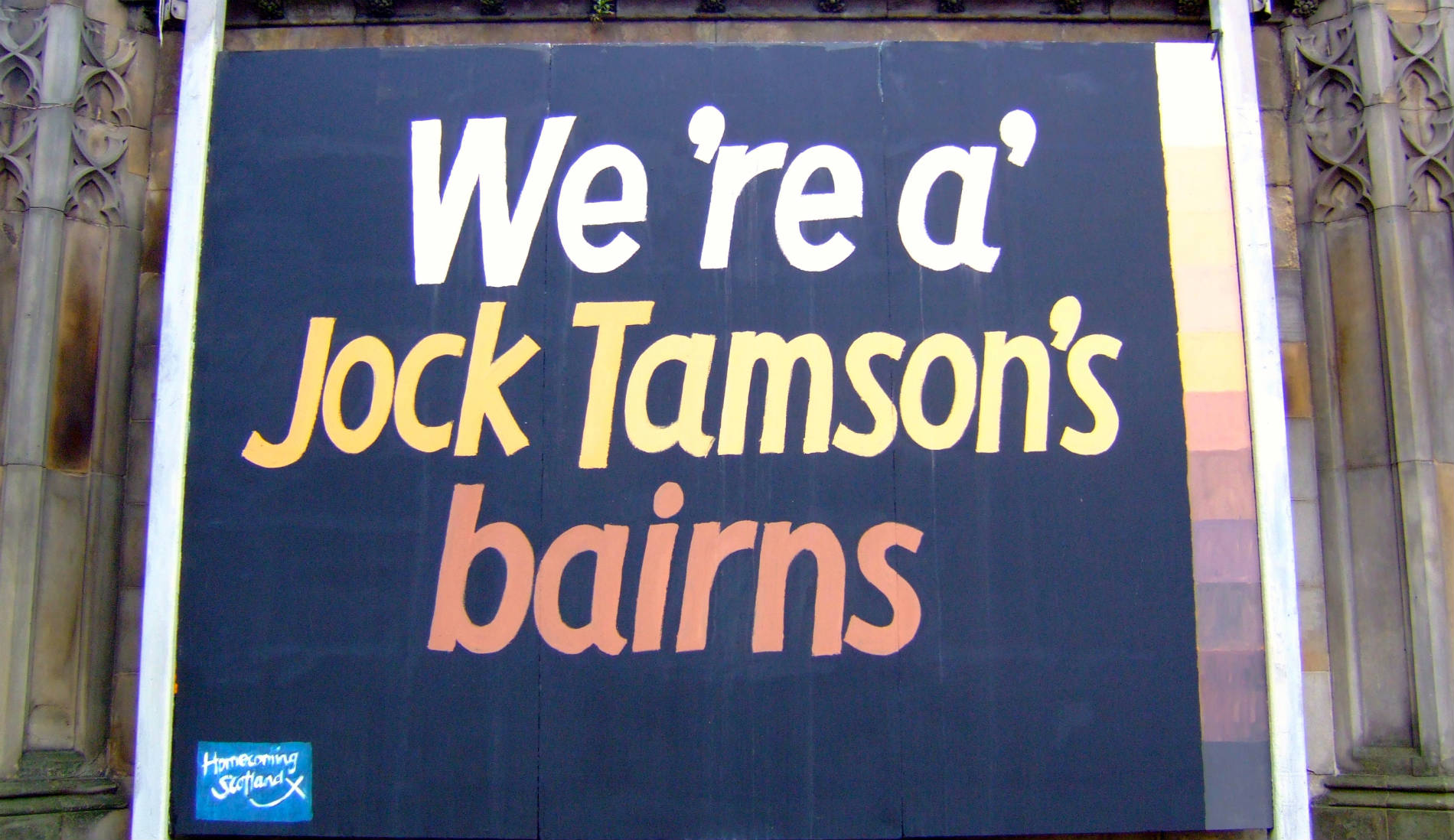

Perhaps Scotland’s National Action Plan for Human Rights can also be seen as part of a wider trend; a country which is involved in a serious internal debate about its vision of future prosperity. The debate about independence in Scotland has combined with a strong social justice discourse emanating from a Holyrood Parliament playing an oppositional role to Westminster’s austerity politics. And it feels like it has created conditions under which people can discuss freely fundamental issues about the country they want to live in.

For instance, there is a serious debate about whether future prosperity might look more like the ‘Nordic model’ of the Scandanavian countries to Scotland’s east, as opposed to the American free-market economic model imported from its west. In a nutshell, this debate explores the attraction and feasibility of Scotland attempting to change the nature of employment, so it can pay more taxes in order to obtain better public services and a more cohesive society.

In Scotland, it feels like competing visions of future prosperity are really being debated, considered and, in the end, voted upon.

As with attitudes to human rights and austerity, visions of prosperity look very different depending on whether you live north or south of the border.

Photo by byronv2