The pain of grieving a loved one is intensified when those mourning are also cut off from the welfare and benefits payments they need to survive. With personal experience of this, Kai Charles explores how UK welfare policy and the legacy of Austerity Britain hurts the poor, disabled and marginalised.

Three days after my eighteenth birthday, my dad died. His death came after a decade of deteriorating health and brought a series of devastating consequences. My family, ever small, shrunk to two: myself and my mum. As a family surviving partially on the benefits my father received we found ourselves navigating the wasteland of grief without income, support, or guidance.

Poverty had hovered near since my early childhood. In the months after his death in 2019 money leaked from us, what savings my mum had managed to maintain throughout his illness dropping daily. That spring, the hills that surround my hometown of Malvern, were unbearably beautiful. In my room the light was broken, so by the flashlight of my phone, I filled sheets of scrap paper with frantic financial plans.

By 2020, we were eating one meal a day: lentil soup shared with our elderly rescue dog, Beano. My mum was forced to reapply for benefits, moved from the combined package of support she had received prior to dad’s death to a period of no support to Universal Credit. We were living on £348 per month.

The house was bitterly cold, and I held Beano close for warmth. Poverty is a slow sort of grief.

Our story is far from unique. Our situation is the culmination of years of neglect under a policy that shaped my life with my father and continues to shape my life without him.

HOW HAVE AUSTERITY AND UNIVERSAL CREDIT DIMINISHED SUPPORT AFTER BEREAVEMENT?

I was ten in 2010 when austerity was introduced by the new Prime Minister David Cameron. Austerity was justified through a combination of faulty economic research and rhetoric and the demonisation of those reliant on state support. Branded with the slogan “The age of irresponsibility is giving way to the age of austerity,” its announcement, framing it as a necessary response to the 2008 financial crash, ushered in over a decade of brutal cuts to healthcare, education, social housing, and the benefits system. As a disabled teenager with two disabled parents, austerity would impact almost every aspect of my life over the following decade and a half.

The key economic policy of the Conservative era, austerity’s specific cruelties are often obscured within labyrinthine bureaucratic systems. For those grieving, austerity stripped back what little support existed. Gutting the benefits system by £37 billion over the next decade and demonising its recipients, austerity is the bedrock of cases like mine. When you frame a group as parasites rather than people, it becomes terribly easy to abandon them at their most vulnerable.

‘To experience trauma whilst in the grip of poverty/Is to break your leg and crawl onwards without rest or splint.’ read the first lines of a poem I wrote two years after my dad’s death. Life under conditions of austerity was a series of dulling indignities punctuated by great, gasping horrors. Bleeding feet from shoes that did not fit, walking over the same threadbare carpet on which I had been born eighteen years prior. Not enough cash for a toothbrush. We were disposable. The world thought little of the grief my mother and I bore.

We weren’t alone in this experience. In 2022, a survey by the UK Bereavement Commission found that 43% of respondents faced financial hardship following bereavement.

In cases where the deceased was cared for by a relative or friend, the bereaved carer faced a double loss of income: the disability benefit received by their deceased loved one and the Carer’s Allowance they received.

This often led to loss of housing, food poverty, and debt. It was clear that people were not receiving the support they needed in the aftermath of death.

The household income of those in receipt of benefits dropped by up to £4000 during the austerity era. This loss in income intensified the effect of bereavement on low-income families. When it is already a struggle to put food on the table the loss of benefits and income that comes with loss hits harder, the more depleted a family’s budget the greater the impact of the bereavement. Rather than offering increased support in cases of bereavement loss becomes just another means through which a household is brought further into poverty.

“Oh, absolutely,” Anna*, a benefits adviser working with young people in Pontypool, south Wales, replies when I ask if austerity has impacted support received after bereavement. “Universal Credit changed things completely,” she says, “you have bereaved people trying to survive on this small monthly payment. People fall into debt. They can’t manage it.”

When I returned home from my first term at university the house was cold. I had been considering dropping out. Grief combined with my intensifying chronic health issues leaving me isolated, hungry, and almost entirely confined to my rented room. I asked mum if any support could be found to help with heating and food, but she explained that a widow’s pension was not available since she and dad were not married. Terrified what the future might bring, I decided to stick with my degree simply for the maintenance loan. My own experience led me to explore how austerity has affected others.

Between 2010 and 2015 the poorest tenth of the population saw a 38% cut in net income. Today, more than a decade after Chancellor George Osborne’s initial budget, austerity has brought the benefits system to its knees. Underfunded and incentivised to reject new claimants wherever possible, it holds little space for those who are particularly vulnerable.

Every Thursday morning, in the small Midlands town of Malvern, Elaine Lawson sees the impact of austerity first hand. Elaine is one of a group of volunteers, community support workers, and advisers who come together to provide tea and advice to struggling people. “It’s just a really nice space. Some people don’t even come there for advice, just to meet others and have a chat,” she tells me. “But it’s hard when the services that people are relying on are just falling apart. Volunteers are trying to hold everything afloat.”

TENANTS’ SUCCESSION RIGHTS AND THE DEMISE OF SOCIAL HOUSING

Jerome* was a friend of Elaine’s. At 18 he lost his mother. Two weeks after her death, he received an eviction notice, and he was homeless by the month’s end. “Putting him through that was hideous; the timescale was just insane,” says Elaine.

Jerome fell prey to a painful combination of social housing scarcity and succession rights reform. Succession rights refer to passing on the tenancy of a home to a successor after a tenant’s death. Before 2011, council housing tenants could pass on there tenancy to any family member who had lived at the property for at least 12 months. But this changed with the Localism Act 2011.

A contemporary of austerity, the Localism Act addresses the distribution of power between central government and local councils. As part of its reforms, it weakened the succession rights guaranteed to social housing tenants. In its wake, the conditions required of a potential successor became harder to meet.

Now, only a spouse or partner has the right to be named a successor. And although local councils could allow a successor who was not a spouse or partner at their discretion, in a climate defined by scarcity, councils were keen to reclaim properties as quickly as possible after a primary tenant’s death.

Read more: Alternative voices on austerity

While the Localism Act itself was not explicitly related to austerity, its impact on succession rights and social housing were arguably motivated by austerity budget cuts. “I think the change to succession rights reflected aspects of the Coalition Government’s housing policy,” says Wendy Wilson, former Head of Social Policy Section at the House of Commons Library and author of the House of Commons brief on succession rights. “The Affordable Homes Programme was halved as part of the government’s austerity measures—it’s possible to see the change to succession rights as one way of bringing more social homes back into the allocation process and to promote a more efficient use of council housing stock.”

Wendy’s insight reveals the painful choice faced by councils across the UK, who are caught between a rock and a hard place. Throughout the 2010s, extensive budget cuts to public services and welfare provision drove demand for social housing. The failure by successive governments to meet this need through the creation of more homes, combined with a reduction in existing properties through right-to-buy schemes and demolitions, created disastrous conditions. Social housing providers are increasingly incentivised to evict existing tenants in order to prioritise particularly vulnerable people who have spent years homeless or in temporary accommodation.

“The context is relevant,” says Wendy, “Social housing is a scarce resource. As of March 31, 2024, 117,450 households in England were in temporary accommodation, having been placed there by councils after applying for assistance as homeless.”

When a tenant dies, councils are split between the need to free up housing stock for those on the ever expanding waiting list and the responsibility they have to the current occupant. Over time this has led to a situation where surviving family members or carers are rapidly evicted.

While understandable given the limited resources available, the eviction of residents without alternative housing options can fail to account for the vulnerability that grief presents.

Forums are littered with desperate posts written by people facing eviction. “I’m so lost and scared to inform them as I’ll be homeless,” reads one post from a woman sleeping in the council house she had shared with her mum during the last months of her life. Due to her mum’s illness, she hadn’t thought to inform the council that her daughter had moved in with her. “I’ve only just accepted the fact she’s gone honestly,” she responds to one commenter. In another post, a 19-year-old girl who had been sharing a council house with her mother for 17 years writes: “I just wanna stay in my own home, it was bad enough losing my mum”.

“I can see it from both sides,” says Elaine. ”These systems are just completely overstretched, but it is ruthless. A death happens, and people are just left in the worst situation.” Elaine sounds exhausted. The situation can feel impossible.

Austerity and punitive welfare policies force public services to exist in impossible conditions. No matter the decision made, a vulnerable person will be harmed. The issue of death and social housing cannot be resolved until the issue of austerity’s impact on social housing stock is resolved. Until that time, councils will remain conflicted, rushing evictions of grieving people to make room for vulnerable trapped on an ever-growing waiting list. This does not mean measures could not be put in place to offer some protection to the grieving.

The UK Bereavement Commission recommends that landlords, whether private or social, be required to give at least six months’ notice for evictions after a tenant’s death. Another suggestion, raised in a letter to The Guardian, is to make bereaved carers a priority category for social housing, increasing their chances of being offered alternative accommodation if evicted.

Even where alternative housing is offered, issues can arise. Back in Pontypool, benefits adviser Anna explains: “In my area, there’s a real lack of one-person accommodation. When you have a person who’s already lost income due to the death and is now moved to, say, a two-person property, they then have to pay an unoccupied room charge. This can lead to them being unable to afford the rent and, as a result, falling into debt or facing eviction.”

In both the benefits system and social housing, austerity has caused a chain reaction that leaves grieving people in a punishing situation. Without major investment in these services and a change in government approach, we will continue to see people failed in the aftermath of devastating loss.

WHEN GRIEF COMBINES WITH RAPIDLY DETERIORATING LIVING CONDITIONS

In the wake of my father’s death, grief itself became a luxury. As my family fell towards poverty, I set aside my mourning to manage the financial and social practicalities of his death. This experience is all too common.

When a person has to manage grief while struggling to meet basic needs, finding space to mourn becomes impossible. Grief is “not only emotionally painful but also profoundly disorientating,” explains Philosophy Professor Matthew Radcliffe, author of Grief Worlds. Facing financial upheaval in these circumstances can lead to people either suppressing grief, adopting unhealthy coping mechanisms, or struggling to navigate a complex system where limited support can be hard to access.

People who are homeless after eviction, struggling to eat due to loss of income, or facing both challenges are trapped in a vicious cycle where grief combines with rapidly deteriorating living conditions. “It’s when everything starts to spiral,” Anna says. “It’s a massive impact on someone’s mental health. Many don’t have the capacity to improve their financial situation after a death.”

On top of this comes the cost of the funeral, wake, and burial. “They won’t even collect a body without a downpayment,” Anna explains. While a limited fund is available to help with funeral and burial, the maximum amount, £1,955, doesn’t cover even the most minimal funeral and can only be accessed if all surviving family members meet strict conditions.

A mother-of-two, featured in the UK Bereavement Commission Report, faced the agonising consequences of these costs. Using the money that would have ordinarily gone towards rent and food to pay a £1,000 deposit to a funeral director, she was unable to keep up to date with rent payments. Within months she and her children were facing eviction.

When my dad died, the one thing that kept me above water was the community that supported us. Raising the money needed for a funeral and wake, the early solidarity carried me through the gruelling weeks and months that followed.

My dad was well-known in our town, a long-term activist and busker who’d lived over seven years in a tent in the hills that surrounded it. He seemed half man, half local legend. At his funeral, people filled every seat, standing three rows deep around the back and sides of the crematorium. Not everyone has access to this level of support.

Across the country, Death Cafes aim to remedy this, providing, at the very least, a place to share grief. Where they don’t exist locally, Zoom has allowed people from around the world to meet online. While these cafes cannot provide financial support, the emotional connections they foster can help isolated people navigate the challenges of grief.

Other support groups include community gatherings like the one in Malvern, where Elaine volunteers—spaces where people can access advice and guidance, alongside cups of hot tea. When I ask Elaine what she’d like to see in the future, she suggests better education on the practicalities of death and dying. Many people are completely unaware of the impact that loss can have in terms of income, housing, and funeral costs. “Just a bit of time to prepare could change things massively,” she tells me.

In the UK, grieving people face a harsh reality: overstretched services cannot meet the needs of a growing number of people in poverty, and public bodies often fail to recognise how death affects a person’s ability to handle everyday challenges. The result of this is a response to grief that punishes rather than supports.

If grief and death are said to unite us—experiences as universal as they are devastating—the cruelty of indifference shown to low-income people in times of loss highlights the depths of dehumanisation to which the poor, disabled, and marginalised have been subjected in austerity Britain.

If we do not confront the legacy of this policy and the damage it has caused to an already insufficient support system, we risk the wholesale normalisation of the abandonment of grieving people.

*Names changed to protect anonymity.

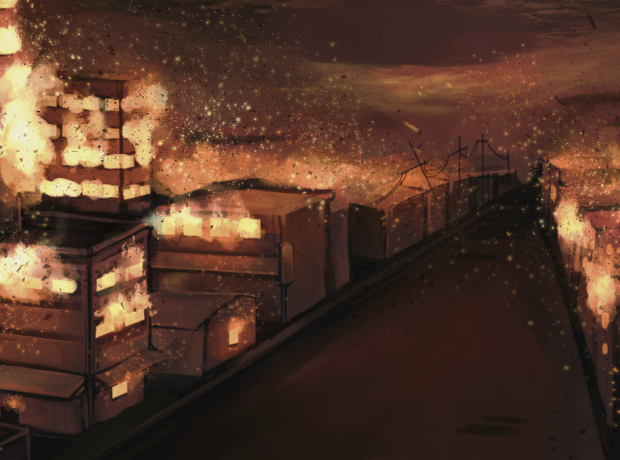

All artwork by Jiraporn Puengprayotekij.

Read more: