WOMAD presents an incredible menu of music and food from every corner of the world. There is a dizzying array of Cambodian rock and roll bands, Malian blues bands and Palestinian electro hip-hop bands. And within all of this stories of campaigning and struggle. The festival has been the perfect place for Indian human rights charity Action Village India to run their fundraising Madras Café, where they share the stories of their projects and serve mouth-watering dhosas, bhajiis and thalis for people who would sneer at the thought of a chicken vindaloo.

Poetry Madras Cafe WOMAD

The queues went out the door for the famous food, but one thing the eaters were not expecting this year was a poet standing on a rickety plastic chair bellowing out human rights poetry through a microphone. They were there for bhajiis, not poetry, but because of the crowd that WOMAD draws, the Lacuna team and I were able to engage these diners in key discussions about human rights in India whilst they sipped masala tea and ordered more sweet meats.

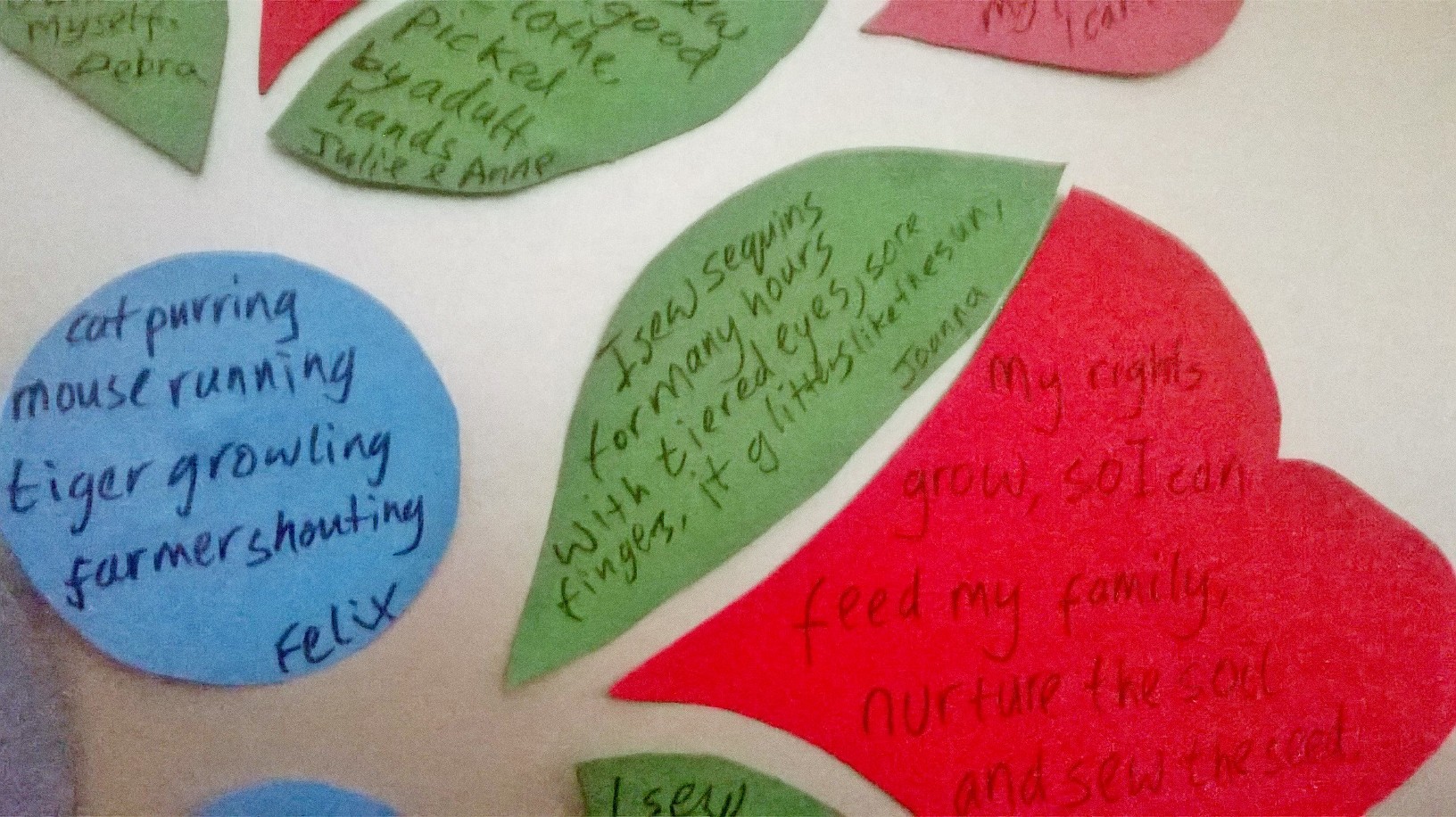

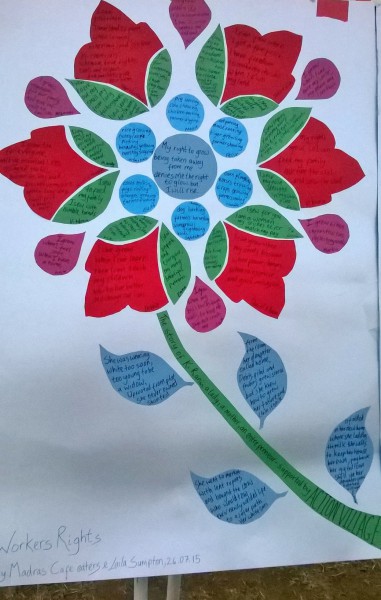

Over two days I worked with the Madras Café customers to create two poetry mosaic boards, using traditional Rajasthani designs from Mughal tiles. We filled each coloured piece of card with a fragment of poetry that explored their understanding of human rights. I needed their words to build both the poem and the mosaic and depending on how keen they were to speak with me I used different writing prompts on different sized pieces of card. The trick of engaging people in poetry, who have not come to a venue with poetry in mind and perhaps have not written a poem since school, is to make the prompt as accessible as possible.

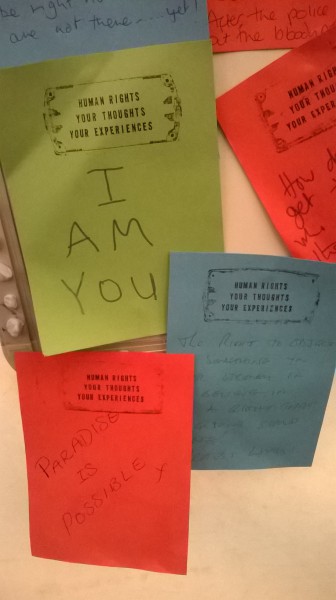

The first day of mosaic building used a flower design and focused on workers’ rights in India, with children writing some fantastic Indian farmyard kennings. Adults responded to a range of prompts such as ‘I sew to’ and ‘I grow when…’ causing people to think both practically and creatively about what helps and hinders people grow and develop. The next day focused on the theme of protest, and for this I created a lotus flower and a peacock mosaic. I used prompts such as ‘I march for…’ and ‘I stand for’ asking contributors to think about what motivates them to take a stand whilst letting them know about the campaigns that Action Village India are supporting in India.

I also created some hastily and simply written pieces which were a half-way house between poem and case study, looking at the story of how AVI supported a fishing community to campaign for their right to fish their waters titled ‘Sea vigil’ and how micro-finance loans helped widows become self-sufficient and gain their independence titled ‘The story of K Rani’.

Poetry Madras Cafe WOMAD

The mosaics drew in bystanders, intrigued by the small messages in each tile of the mosaic. I was amazed that people came back with new ideas to add to the poem later that day or brought their friends and family to the tent to see their contribution. Around 60 people contributed poems to the human rights poetry mosaics, mostly whilst queuing for food. They would read what had already been written and with prompts and support from myself, add a new angle to the different fragments of the poem. Often I would ask our contributors to think of more vivid and emotive language, moving their statement about human rights into a more creative and poetic comment. We had to be careful not to veer too much in this direction though as the last thing myself and the Warwick University Lacuna team wanted was a group poem which depicted only suffering, pity and victimisation. The work of Action Village India would not fit with this: they support local campaigners and human rights defenders at the community level to protect their rights to land, education and gender equality.

It is always inspiring when someone who initially denies all ability to write creatively, creates a small poem and can see their work supporting the bigger picture the mosaic was building. People might have come to the Madras Café for bhajiis, but quite a few left with poems and a renewed appetite for campaigning.

Read the poems here