I’ve been an environmentalist for more than 15 years. I’m also pragmatic about any individual’s ability to change a massive and hugely flawed system. I do passionately believe that individuals can make a difference. But I would argue that this requires imagination more than mass movements. We need to think about operating both at the margins of the system and within the ‘crawl spaces’ that exist today. I also see that the only way to mend our damaged environment is to mend ourselves.

If the fossil fuel era has been about anything, it has been about acting, doing. Whenever we have a problem, we do something. When are we ever encouraged to pause and reflect? When do we apply a filter to our thoughts that allows us to sort the good ideas from the bad? Rarely. When activity serves as the sole measure of success, reflection loses its value. In political or activist circles, not ‘doing’ is likely to bring an accusation of failing to deal with a problem.

Yet I would argue that our societal and environmental predicament is precisely the result of too much doing: of billions of people acting unwisely and far too often. It is this fixation with activity for its own sake which has led to the squandering of our energy reserves and to the wrecking of a good proportion of the planet. Why this fixation with activity? In anticipation of something better, of course. If Western culture stands for anything, it is doing to achieve, to get somewhere else, to move forward, to progress.

Our societal and environmental predicament is the result of too much doing

The cult of progress is, of course, based on an increasingly debatable assumption that the future is going to be ‘better’ than the present, and very much better than the past. The future discounts the present and the past, an idea that lies at the heart of economic theory and accounting practice. It’s as if any present or past good will never be as good as what will follow in an imagined future. In spite of plenty of evidence to the contrary, this is the assumption that our society is expected to place at the heart of its collective life’s work. Progress thus becomes the clarion call of those who would benefit from our ever-increasing activity and, with it, our ever-increasing dislocation from the rest of nature and the things that actually make us human.

In the unfolding era of scarcity, and with the real prospect of both economic and environmental collapse, I would suggest that we will need to be much more careful in our thinking, and much less prone to simply acting. We need to be careful about how we respond to the challenges the future throws at us. It is too simplistic, for example, to believe that a mass movement for this or a mass movement for that will be the catalyst for changes we might wish to see. Mass movements are simply another form of doing. They utilise the same reductionist thinking that has arguably created many of the problems we have to grapple with today. Mass movements, if they are to last, also require leadership. Call me a cynic, but it seems that leadership, at least on this scale, always fails. Perhaps we need smaller-scale, more human-centred responses?

In pondering all of this, and what an alternative might look like, I find myself increasingly drawn to the word refuge and the idea it embodies. The concept of the refuge – a place to reflect, collect our own thoughts, sift and hang on to the good whilst shedding the bad – could be a powerful antidote to the increasingly illusory idea of progress. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word derives from the Latin word refugium; re meaning ‘back’ and fugere meaning ‘flee’. In other words: walking away.

That’s walking away rather than giving up. The concept of refuge encourages walking away from a broken system and back to the things we enjoy and feel comfortable with. Things that do us good and things that make us human. Above all, fleeing from the things that make us unhappy and insecure. In a world that dances ever closer to the edge of the abyss, be it through financial meltdown, climate catastrophe or the implications of increasing resource scarcity, refuge potentially provides us with an idea that helps us to abandon this mindless pursuit of limitless growth, dressed up as human progress.

Living without reflecting is like driving without looking

Living without reflecting is like driving without looking. Refuge, on the other hand, encourages a collective dropping of the shoulders, breathing more slowly, counting our blessings, sifting carefully the good from the bad, doing things more thoughtfully, waking up and smelling the roses, or the coffee, depending on your preference.

In musing upon the word refuge, and thinking about how, practically speaking, such a concept might manifest itself in reality, I am reminded of the role of monasteries in the ‘Dark Ages’ that followed the disintegration of the Roman Empire in Europe. Damaged by centuries of war, rising costs of maintaining the empire, infighting, civil unrest and corruption at the top of society, the Roman Empire passed away into history. This is a history that resonates loudly with what we are increasingly experiencing today. Ask any Greek, ask any Spaniard, ask the countless hundreds of thousands of Americans living in trailers. Ask anyone in a queue at a food bank.

Photo by Ivan Walsh

Barbarian armies swept in to territories previously held by the Romans, razing cities to the ground and squabbling over land and resources. Whilst cities lay in ruins, monasteries, often because they were remote, developed. Monks relentlessly copied Greek and Roman manuscripts, as well as holy books, thus keeping the nucleus of a future civilisation alive; sifting the good from the wreckage. Whilst not perfect, and prone to some of the same problems and excesses of the system they followed, they did a vital role in bridging the gap between the past and the future.

When a monastery was founded, many people gravitated towards it to enjoy both its spiritual and material benefits. In many cases the monasteries created the nuclei of new towns and cities. Monasteries became stopping-off points for travellers, fortresses during conflict, centres for distributing food in times of famine, hospitals during epidemics and neutral grounds for opposing parties to discuss grievances and make agreements. All of this was in addition to their primary role as bastions of knowledge and skills, and custodians of faith.

As well as preserving knowledge, the monasteries also became the catalysts for new ways of living. They were the inventors of rudimentary machinery, they developed alcoholic drinks and a wonderful diversity of cuisines, they researched basic science, they encouraged new patterns and methods of agriculture and land development, and they established networks of connections with one another. All of this laid the groundwork for a new European culture which emerged from the rubble of the collapse of Rome.

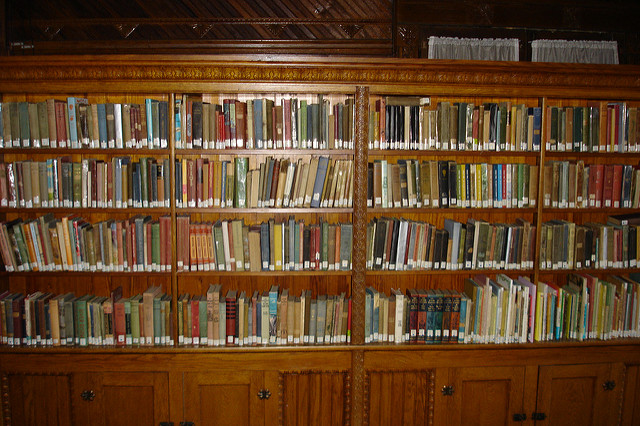

We have countless centuries of collected knowledge. It’s a library. Photo by WordShore

Today, the idea of the refuge encourages us to look back before we look forward. We have countless centuries of collected knowledge. It’s a library. It’s worthy of investigation. It has value. Like the monks that pored over manuscripts for days, weeks and years on end, the time we put into (re) learning from the past will sow the seeds of how we might live in the future. We need to be creating communities that look to the past and then to themselves for solutions.

The whole point of beginning to develop human-scale ideas is that no one person has all the answers. I certainly don’t. All I have is a belief that if we turn away and look inwards we’ll start to address what we actually need. Of course I have some views about what might constitute ‘refuge’. Some are ideas already in use to some extent. Allotments, community-supported agriculture, urban agriculture, small local breweries, artisan bakers, farmhouse cheese making, artisan butchers, small-scale bicycle makers, localised energy production, craft woodworkers, cob builders, timber-framed house builders, small scale clothing makers, local currencies, up-cyclers and many more. Each one addressing real human needs. Each one a result of reflecting upon the weaknesses of the prevailing system, the strength of more traditional methods and the necessity to put human fulfilment and, in many cases, some connection to nature back at the centre of how we spend our time living and working.

It would be easy to dismiss, for example, the growth in interest in allotment gardening here in Britain, or the re-igniting of interest in craft-manufactured bicycles, as quaint anomalies. They aren’t. They point to a growing disquiet with what industrial society has endowed us with. The idea of working in, or on, such a refuge gives us the opportunity to develop a unifying narrative in response to this growing disquiet.

No one person has all the answers

So where might we start? If you like, we start with our own personal monastery; the ‘space’ to reflect upon what we actually think our refuge might look like. It could be a metaphorical space. It could be a physical space. We might pose questions such as: What do we actually need? What fulfils us? What skills do we have to offer? What do we think is worthy of investigation? How do we go about reimagining some aspect of the best of the past? Do we do it on our own or with others? We need to be honest with ourselves: this is partly about seeking out truths and dispelling the myths we have had sold to us. We, all of us, have an inkling of what is wrong. We need to go about this with confidence. Arguably no one else is going to do it for us, no political leader, no mass movement.

I have my own ‘refuge’. I’m using my near decade and a half of environmental doom-gathering to formulate an idea. I’m spending a lot of time reflecting on the writing of thinkers like John Ruskin. I’m pondering what human fulfilment actually means. I’m wondering if our environmental predicament isn’t simply a result of a bigger human predicament. I find myself asking what place there is for truth or even beauty in what we do today. I’m trying to connect this idea of refuge to the way I spend most of my time.

My work life is mostly spent with bicycles. I’m grateful to be able to work with something that generally brings pleasure and is a blessing rather than a curse when we consider the many other ways in which we transport ourselves. I’m not blind to the shortcomings and impacts of an industry which is in general large and globalised. But I carry with me handed-down stories of the way in which my trade operated in the past and what place the bicycle occupied in society. There’s a historical perspective which is worthy of investigation. I’m reflecting upon what role the bicycle might actually play in our unfolding future. It’s currently a work in progress, but the idea of refuge – of walking away – encourages a very different approach to how we go about interpreting the future.

An earlier version of this article was originally published as part of the Dark Mountain Project.

Banner photo from public domain