At the height of the Covid crisis, unprecedented death tolls pushed some countries to the limit. What can we learn from a pandemic that has now claimed the lives of 2.3 million people around the world? How should we manage heavy death tolls in future emergencies? And after seeing some countries resort to burying their dead in mass graves, is now the time to call for an international right to an honourable burial?

New rules and restrictions have been placed on funerals since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, sparking protests in Ecuador, Brazil and Sri Lanka. Around the world mourners have been understandably upset about social distancing rules limiting attendance at funerals and forcing many farewells online. But it was when governments were perceived to be disrespecting the dead and their grieving families that outrage and protests were sparked.

Issues with the mismanagement of dead bodies in Ecuador first emerged with reports that corpses were being left on the streets. Images later appeared showing people sifting through unidentified bodies piled inside open containers outside city hospitals. In one case, the family of an elderly woman was sent ashes after they were told she had died, only to later find out she was still alive and in hospital.

Brazil has had one of the highest Covid-19 death tolls of any country, and in the worst hit part of the country’s remote Amazon region the disease, at its height, overwhelmed the public health system. In the city of Manaus, which has the highest death rate in the Amazonas state, the authorities resorted to stacking coffins in mass graves.

The locals called the graves “trincheiras” as they were reminiscent of the trenches of the First World War. These mass graves were stopped after protests in Manaus but they persisted in Sao Paulo.

Authorities had to perform night time burials to prevent the city from being “the Brazilian version of Guayaquil,” a reference to the Ecuadorian port city where the burial system failed so badly that bodies were left on the streets for days and families were forced to bury their loved ones in cardboard coffins.

In Sri Lanka, where around 10% of the population follows Islam, Muslims were outraged by mandatory cremation orders, which disregard Islamic rites requiring burial and strictly prohibiting cremation. The policy also goes against World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines which allow for both the cremation and burial of bodies in relation to COVID-19.

Amnesty International, along with Muslim leaders and activists, called for the government to reverse the policy, saying: “At this difficult time, the authorities should be bringing communities together and not deepening divisions between them.”

Could failings in the law lie at the heart of all these conflicts?

Currently all policies relating to the “rights” of the dead are governed by non legally-binding “soft law” instruments. The WHO guidelines on the Management of Dead Bodies in Disaster Situations is an example of this.

When a party violates these guidelines there is no legal recourse or damages. Instead, it simply represents a ‘non-observance’ of a principle. Observance is voluntary and there is no mechanism to enforce it.

Given that soft law instruments are relatively ineffective against such grotesque indecencies, perhaps a different approach would fare better – one that empowers individuals with definitive rights and enforces violations with strict penal sanctions.

Calls for these rights are unprecedented as many organisations such as the Last Rights Project have been imploring governments to sign this type legislation for years. It turns out that the mismanagement of dead bodies is not just a contemporary issue owing to a singular pandemic, but in fact a perennial problem which has been swept under the rug.

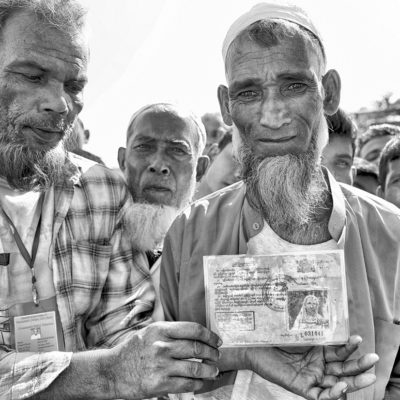

In the case of the Last Rights Project, they have been crusading for a “new framework of respect for the rights of missing & dead refugees, migrants and bereaved family members.” The framework they proposed, the Mytilini Declaration spells out the international obligations of governments in regard to deceased migrants and refugees.

Stipulating the steps they must take for the search, investigation, identification, tracing and burial of the dead. Although no governmental body has yet to sign the agreement, it goes to show how a general right (the right to an honourable burial, or any equivalent) could have a broader scope of applicability.

For instance, this right could offer protection against the mandatory cremation order as well as address the mismanagement of deceased migrants. These circumstances would otherwise be inapplicable under the WHO guidelines as they fall outside the narrow definition of a “disaster”.

Of course, enacting such a right would have its own difficulties. From a policy standpoint it would place strain on the government’s resources to ensure proper enforcement and monitoring. This would be especially difficult during times of emergency, since the government must balance the needs of the living with the rights of the dead. This standard may be too high for developing countries and even some economically wealthy countries. So, the law must be pragmatic enough to account for these realities, but not too ambiguous to defeat the original purpose altogether.

Despite these drawbacks, there is good reason to push for an international right to an honourable burial (or any equivalent). After all, it already exists to an extent. Examples of this could be seen in Article 130(1) of the Fourth Geneva Convention, where it states that deceased prisoners of war should be… “honourably buried, if possible according to the rites of the religion to which they belonged and that their graves are respected, properly maintained, and marked in such a way that they can always be recognized.”

Detaining authorities must also forward a list of graves to the Information Bureaux which would include all the “particulars necessary for the identification of the deceased internees, as well as the exact location of their graves.” The Geneva Convention is signed by 196 different countries so there is at least recognition of an obligation towards the dead.

If, even in war, this imperative is honoured why can’t we honour the same for citizens, for migrants and for refugees alike?

Article 9 of the ECHR, which addresses freedom of thought, conscience and religion, provides that the “Freedom of worship also applies to the manner of burying the dead inasmuch as it constitutes an essential aspect of religious practice (Johannische Kirche and Peters v. Germany (dec.)).” This provides a strong foundation for developing more defined rights associated with burial.

Ultimately, the creation of this right would ensure the deceased person was treated with respect and that their families would not endure further suffering. And for those nearing death, it could also provide a moment’s comfort, knowing that their religious rites, customs and cultures would be honoured after their passing.

Main image by Isaac Quesada.

Read more:

Will Covid strip what few rights the Rohingya refugees have left?

Will Covid strip what few rights the Rohingya refugees have left?

How Europe is using coronavirus to reinforce its hostile environment in the Mediterranean

How Europe is using coronavirus to reinforce its hostile environment in the Mediterranean

Coronavirus reminds us that America doesn’t like Black people

Coronavirus reminds us that America doesn’t like Black people