Covid-19 is killing Black Americans at three times the rate it’s killing white people, and racist attacks – by both the public and the police – are leading the news agenda. Kathryn Graves explores how the pandemic has exposed the institutional racism that defines the second-class status of Black people in the USA.

Black people are dying

When my father, a commercial airline pilot and essential worker, informed me that he would indeed be working at least through the month of April, I felt a palpable tightening in my chest. The sheer nature of my father’s job necessitates sharing an enclosed space with dozens, if not hundreds, of different people every day, significantly increasing his likelihood of infection.

When I later received a phone call from one of my close friends, a fellow PhD student now resigned to working from home, she was close to tears. Her father, a mechanic, was also deemed essential, and would continue to go to work for the foreseeable future. As the daughters of Black men working essential jobs during a global crisis, our fears aligned – fears that our fathers would join an ever-growing statistic of Black people getting sick and dying of Covid-19, in a country that has shown it could care less.

Across the US, African Americans are contracting the virus and dying at rates astronomically disproportional to their white counterparts. 70% of Chicago’s first reported cases were Black, even though Black people only make up 30% of the city’s population. In the state of Wisconsin, the 6% African American population made up 40% of Covid deaths, and the trend hardly stops there.

Read more: George Floyd – Why the sight of these brave, exhausted protesters gives me hope

A recent Mother Jones report found that of the 28 states that provided useable racial breakdowns of affected communities, the vast majority demonstrated a measurable disparity between the percentage of Black people in the population and the percentage of Black people either infected or dead. It takes only a cursory glance at the steep socioeconomic inequalities between Black and white communities to piece together how this is could be case.

As Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, cardiologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, writes: “Being able to maintain social distancing while working from home, telecommuting, and accepting a furlough from work…are issues of privilege. In certain communities these privileges are simply not accessible.”

Consider “certain communities” here as shorthand for “poor, predominantly Black communities.”

Black people additionally tend to live in food deserts and high crime neighbourhoods with densely packed housing, all of which are risk factors, and all of which contribute to the number of Black people contracting the virus.

Anti-lockdown protesters during the coronavirus pandemic in Huntington Beach, California – by Russ Allison Loar

Nonetheless, the Trump administration has been urging states to end stay-at-home orders, with conservative pundits concluding that this crisis has turned out “not to be quite as dangerous” as was initially thought. How could this be, when so many were and are still dying? One need only look to the signage of those protesting the stay-at-home orders to discern the answer.

Brandishing statements like “I want a haircut!” and “Sacrifice the Weak, Re-Open TN [Tennessee],” these predominantly white protesters have demonstrated a clear disinterest in flouting risk and returning to work themselves – and a clear desire for those who provide them services to do so.

With Black Americans vastly overrepresented in the service-sector, many without healthcare, their lives are on the line – and for pundits, protesters, and the president alike, that’s a minimal cost to reopening the economy. The bottom line is, it doesn’t matter how many people are dying when those people are primarily Black.

Despairingly, this deference to white privilege and supremacy comes as no surprise to the Black community. Many view the societal response to the virus as another manifestation of Black second-class citizenship, reminiscent in some ways of President Bush’s fumbled humanitarian response to Hurricane Katrina. On her pop-culture podcast “The Read”, co-host Crissle West punctuates the stark outlook in her plea for Black Americans to do everything possible to stay home: “…If it gets that bad and you can’t breathe on your own and you have to go to the ER, who do you really think they’re going to give a ventilator to?…you can’t trust these people to actually value your life on the same level as a white person’s life.”

Workers wear protective visors as they sanitise New York subway cars during the Covid pandemic – by MTA

Black people are being profiled

The murder of Ahmaud Arbery by two armed white men earlier this year again reminded us that, for Black people, even the most mundane activities – from running outdoors to entering an apartment to leaving an Airbnb to sleeping in a common room to grilling in a park to walking in a white neighborhood to holding a toy gun – could result in harassment, police brutality, and death. The Covid pandemic has accentuated this injustice to an almost satirical degree, with Black people being profiled and harassed by police for not following safety guidelines, and also for following safety guidelines.

Amy Cooper, wearing a face mask and choking her dog, confronts Christian Cooper in New York’s Central Park

Just this past week, two incidents, both caught on camera, exemplify the harassment and abuse of black people in America: the first by a passer-by in New York’s Central Park, the second by a police officer in Minneapolis. When bird watcher Christian Cooper, a black man, asked dog walker Amy Cooper, a white woman (and no relation) to leash her dog – as per the rules of the area of the park they were in – Ms. Cooper took affront, warning Mr Cooper she was calling 911 “to tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life.”

Later that same day, George Floyd died in Minneapolis in a way that exemplifies the impact a call like that made by Amy Cooper can have. Mr Floyd, 46, was arrested by police responding to a call about someone trying to use potentially counterfeit money in a shop. Video footage then shows a white cop pinning Mr Floyd to the floor with his knee on his neck as Mr Floyd repeats “I can’t breathe,” just as Eric Garner did during his fatal arrest in 2014.

In New York City, the US epicentre of the disease, police were observed on separate occasions punching a man in the face and knocking another unconscious while enforcing social distancing rules by breaking up gatherings in predominantly Black and Hispanic neighbourhoods. However, this violent approach to public health seems reserved for people of colour, as elsewhere in the Big Apple, crowds of mostly white residents and tourists sunbathed and gathered in parks, many not wearing masks and yet undisturbed by the NYPD. Where there was police involvement, it was to hand out masks to park visitors.

Meanwhile, In Wood River, Illinois, two Black men were followed by a police officer from a Walmart store into the parking lot for “acting suspiciously.” The suspicious act? Wearing protective masks. The officer demanded the men’s identification, citing a city ordinance prohibiting face masks – an ordinance, which, incidentally, doesn’t exist. This incident underscores a broader concern, that Black men are inherently viewed as more suspect when wearing masks (and especially homemade mask substitutes like handkerchiefs).

More broadly, these instances collectively illustrate that the coronavirus as a lose-lose situation for Black people who exist in public. This pandemic has created bold new ways to police and marginalise Black bodies.

Protesters wear Black Lives Matter face masks at 38th Street and S. Chicago Avenue in Minneapolis on Tuesday after the death of George Floyd – by Lorie Shaull

Black people are being watched

Despite seemingly substantial reporting across the news spectrum on the ways in which Covid-19 is ravaging the Black community, some officials argue that reports are often woefully incomplete, missing crucial race and ethnicity data.

Scott Pauley, spokesman for the Centers for Disease Control, emphasized in a recent statement the need for “supplementary surveillance systems” to better capture this information and track the disease – a sentiment widely shared by those in healthcare and data science communities. Aside from proper screening protocols at locations like schools and workplaces, academics and tech giants like Google and Apple are developing “contact tracing” apps that track the spread of the virus by tracking individual behaviour.

Grocery shopping during the Covid pandemic in Virginia – by Ronnie Pitman

These apps make use of Bluetooth capabilities and GPS information, and may eventually involve scanning people’s social networks to track interactions.

Any American citizen would justifiably be apprehensive about the numerous ways in which these dependencies on big data could compromise privacy. For Black Americans, this apprehension is underscored by a long history of being over-surveilled in this country.

From the lantern laws of the slavery era to stop-and frisk policing policies in the 21st century, Black people have been perpetually under the intrusive gaze of those in positions of authority – a gaze with the power to limit access to resources like welfare and strip individuals of their dignity and autonomy. Now, as big data emerges as a key player in the fight against Covid, African Americans may be experiencing understandable PTSD. How might this data be weaponized against us? How will it impact the already abysmal treatment of Black people by non-POC healthcare professionals?

Read more: An open letter to the Desi community on colourism and anti-Blackness

The effects of Covid related mass surveillance and data collection has yet to be quantified, but this much is true: with it comes no guarantee of benefit for the Black community.

Black people are American citizens

Amidst all the conversation surrounding this pandemic, there flows an undercurrent of curiosity as the United States struggles to maintain. What will remain of this country, on the other side of Covid? Surely some of the institutions that once upheld this nation will crumble under the weight of an emaciated economy.

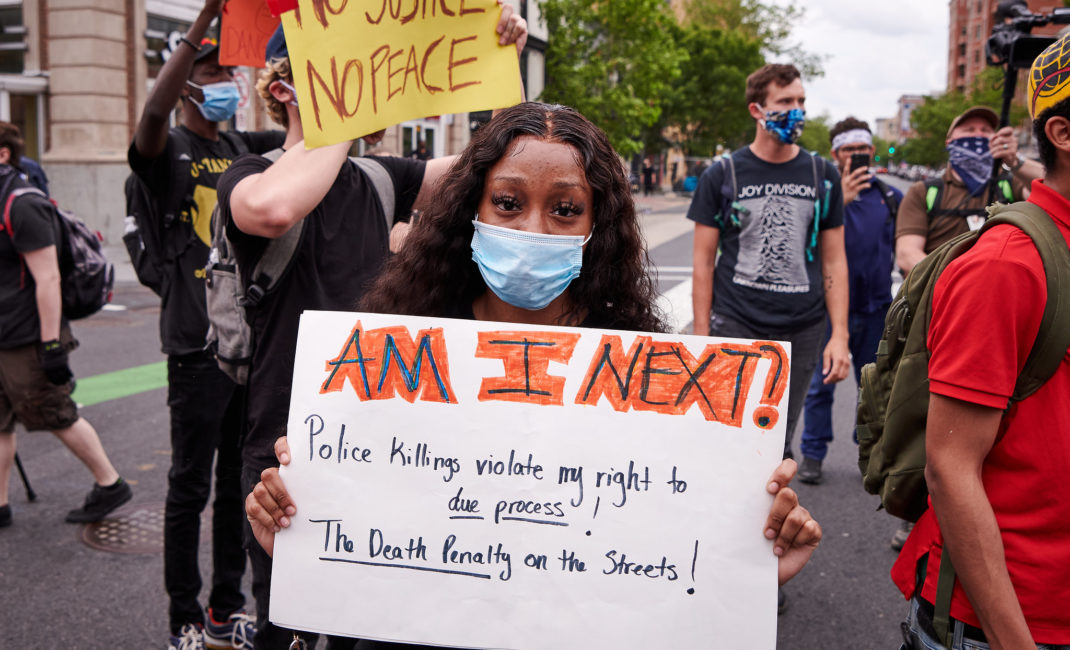

Protesters at a Black Lives Matter march in Washington in response to the killing of George Floyd – by Geoff Livingston

More importantly, what will become of the American people? Throughout the past couple of months we’ve heard heartwarming stories of landlords forgoing rent for struggling tenants, people delivering groceries to those most at risk, and teachers checking in on their beloved students (from a safe distance, of course).

But as the racist sins of this country are laid bare, the occasional kind gesture is simply not enough. Employers must practice empathy and compassion and remember that by forcing their employees to return to work, they are literally endangering human lives.

Read more: George Floyd’s death is the same old story – but in the new normal of Covid-19

Cops must face their implicit biases and resist the temptation to over-police blackness. Tech giants must systematically assess potential ethical violations before unleashing unbounded surveillance on the most vulnerable populations. If Black Americans are to achieve full citizenship, America must begin the process of dismantling the racist systems this pandemic has so thoroughly exposed – for my father’s sake, for mine, and for all Black people in this country.

Main picture by the Metropolitan Transportation Association of the State of New York.

Read more:

- Am I a person or a colour? By 14-year-old writer Vallentina Mujaji

- US police shootings: The stories behind the statistics

- Benjamin Zephaniah: “All the books have to change. The way we educate has to change.”