The #FreeHer campaign by the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls is reimagining approaches to equality, community and justice for imprisoned women and mothers. Beatrice Spadacini explores the work of grassroots abolitionist activists and their fight to defund America’s repressive criminal justice system, invest in community infrastructure, and combat its treatment of minority women in prisons.

On a sunny spring day in Washington DC, hundreds of women set out on a protest march from the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal church, the oldest Black church in the nation’s capital.

Danielle Metz, a member of the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls (National Council) joined hundreds of other women, accompanied by their families and allies, to deliver an urgent message for President Joe Biden before Mother’s Day: stop building new federal prisons for women and girls and invest money in communities instead.

For Metz, like for many other women attending this march, the issue is personal. At the age of 18 Metz was a single mom eager to find a partner to help her raise her son. The man she fell in love with and eventually married turned out to be the leader of a powerful drug ring in New Orleans, Louisiana.

When the police caught up with him, Metz was accused of supporting her husband’s cocaine distribution enterprise and was given three life sentences, plus 20 years. The fact that she had no prior conviction and was peripheral to her husband’s business made no difference. When Metz went to prison at the age of 26, she left behind two children: a seven-year-old boy, and a three-year-old girl.

It was the early 1990s, when the so-called “Crime Bill” was passed by then President Bill Clinton and politicians wanted to show they were “tough on crime.”.

Danielle Metz

“Women have been languishing in prisons for decades,” says Metz, who was the last woman to receive a commutation of her sentence – an official forgiveness – from President Obama in 2016 after spending 23 years and eight months in a California women’s prison. “I am now free, but I feel guilty because my friends are still inside. That is why I do this work, because I have been on the other side of that story.”

President Biden was a Senator for Delaware when the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 – aka Crime Bill – was passed. All the women participating in the march felt strongly that President Biden has a moral obligation to rectify the harsh sentencing that in the 1980s and ‘90s disproportionately impacted communities of color across the US.

Formerly incarcerated women from all states marched to Freedom Plaza, an iconic square surrounded by federal buildings and fancy hotels. Their children, husbands, sisters, and mothers walked beside them.

Locked up, but not forgotten

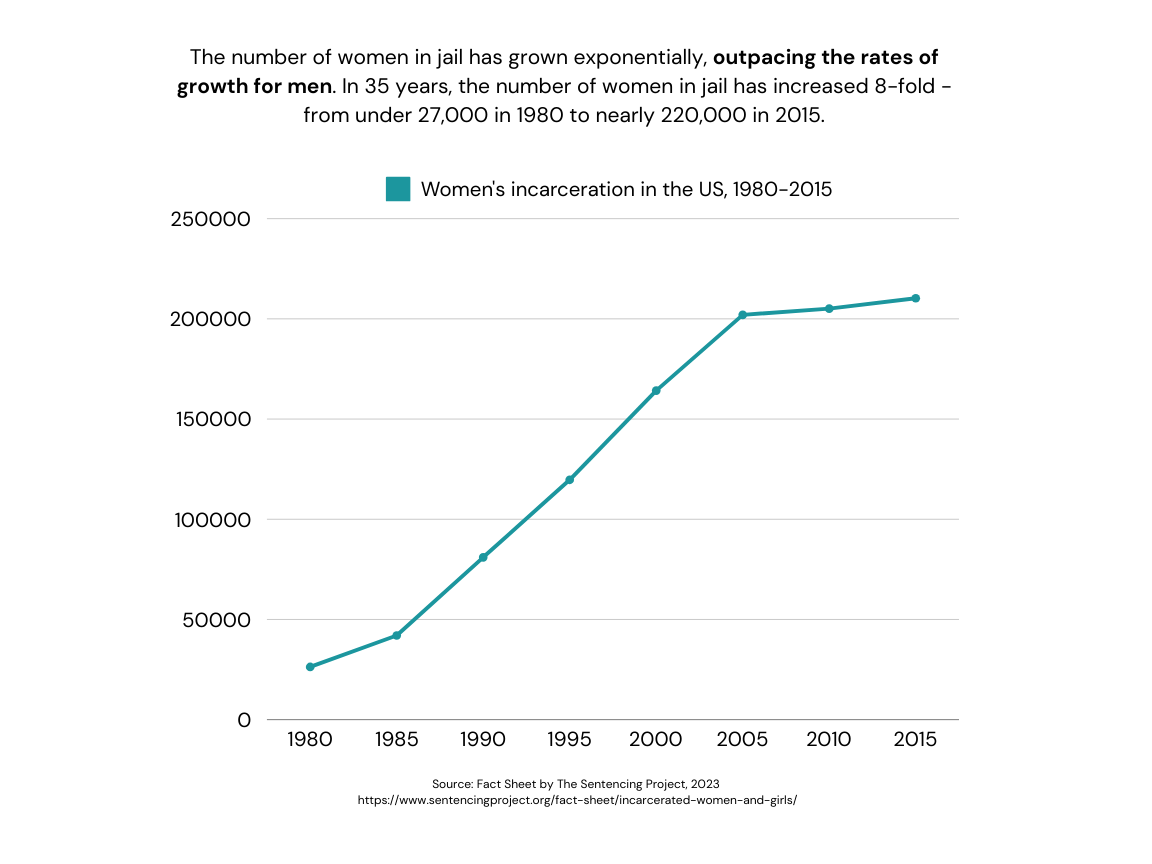

The march drew attention to the almost 200,000 women who are currently locked up in US prisons and jails.

Research on the global prison population shows that the US has the highest incarceration rate of women in the world. Despite being home to 4% of the world’s female population, the U.S. accounts for over 30% of the world’s incarcerated women.

Though President Biden has reduced a higher number of sentences for non-violent drug crimes than any of his predecessors, activists say he should do much more.

Read more: Banned books behind bars

“We have sisters who have been in federal and state prisons for 30, 40 and 50 years,” said Andrea James, Founder and Executive Director of the National Council, during her opening speech as she read out loud the news that President Biden had just pardoned 11 people and shortened prison time for five.

“But what are we talking about here? We got thousands of women buried in prisons across the country that need to come home! Free the long timers! Free the elderly! Free all the women who have been raped in prisons!”

Sexual assault inside prisons and jails is a risk for both men and women, but especially for female inmates as reported by The Appeal, a US news organization. In her remarks, James was also referring to a soon-to-be- closed women’s federal prison in Dublin, California, where employees were found guilty of sexually assaulting inmates.

Michelle West, one of the longest serving first-time female offenders with a double life sentence, is among the women scheduled to be moved from that facility. Her name was on many placards carried by the women at the march.

Female incarceration harms communities

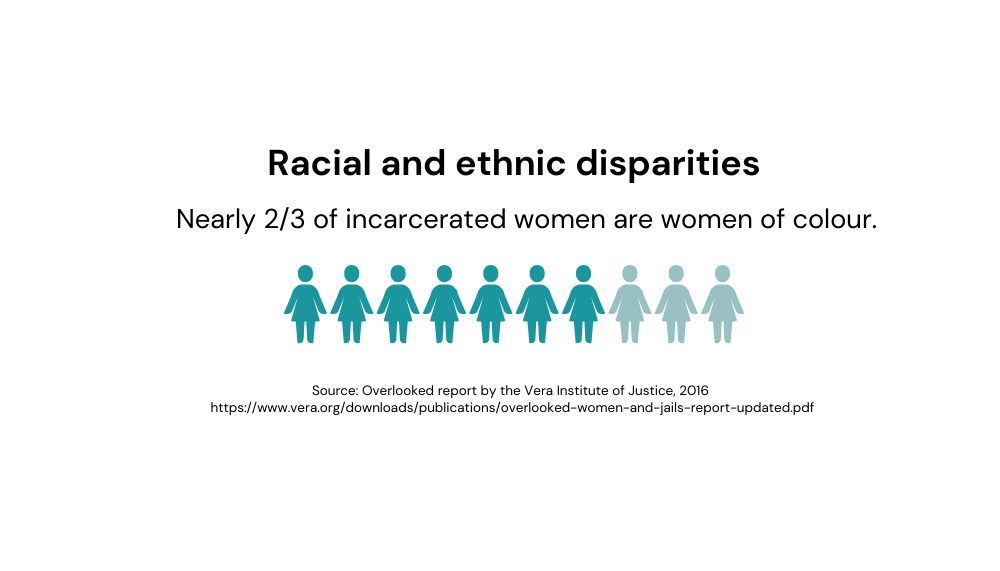

A report on racial disparities by The Pew Charitable Trusts, states that as of the year 2000, Black people made up almost half of the prison population while representing only 13% of the US population. In local jails, according to the Vera Institute for Justice, two out of three detained women are women of color, primarily Black and Hispanic.

Over half of the women held in American jails have not been convicted of a crime and are waiting for a court date.

In the US justice system, the “bail” is the amount of money that the judge sets for the defendant to be released from custody while waiting for a trial. Many women in US jails do not have the means to pay for bail, and almost 80% of them are mothers. Most are single parents and the primary caretakers of their children.

When Betty Washington was incarcerated in 2011 she was charged with conspiracy of bank fraud. Her name was on her husband’s bank account, but she was unaware of his business dealings. When she was sent to prison, she left behind three children in the care of her own mother. Originally from Montgomery, Alabama, Washington was sent to an out-of-state federal prison in West Virginia.

Women’s prisons are fewer and farther apart than men’s prisons. The distance made it impossible for her children to visit her. The separation was especially hard for her youngest daughter, who at the time was only three years old.

Betty Washington

“I remember when I came home, my youngest daughter asked me if I was still her mommy,” says Washington who is a nurse by profession and one of the winners of the prestigious Soros Justice Fellowship for her advocacy work with ageing prisoners.

“We need to start looking at clemency more. Some of the women in prisons have been incarcerated for decades,” she adds.

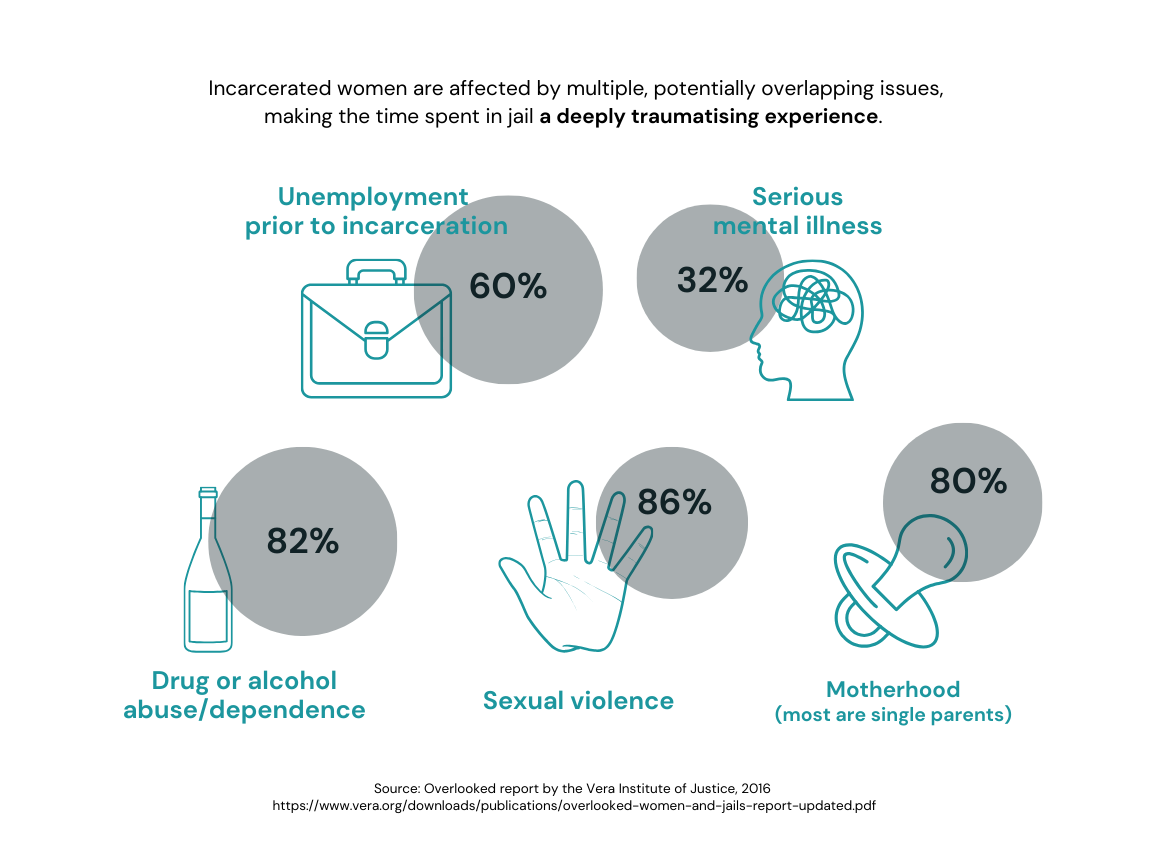

Clemency, which is defined as an act of leniency or forgiveness, is one of the asks of the National Council. This is urgent, they say, because a lot of incarcerated women were given harsh sentences during the war against drugs in the 1980s and ‘90s. Research shows many have a history of trauma.

Data in the Prison Policy Initiative report Women’s Mass Incarceration, The Whole Pie 2024 indicates that many of the women in state prisons suffer from addiction, mental health problems, and have experienced homelessness in the year prior to their arrest. Parental neglect and sexual abuse in early childhood are common factors that can lead to destructive coping mechanisms.

Representing All Incarcerated Women

Despite the seriousness of the topic, the mood at the march on April 24 was festive and music was blasting for several hours in between speeches at Freedom Plaza. The playlist was energizing, and the celebration was in stark contrast to the violence unleashed by police on pro-Palestinian students simultaneously protesting across US college campuses and universities.

Activists took to the stage in between tunes like Gloria Gaynor’s classic I Will Survive, and Shackles, by Mary, Mary. One of the women I met was Ashunte Coleman, co-founder of LIPS Florida, an organization that supports the reentry of trans women back into society.

“As a Black transgender woman, I came here to represent my sisters in this fight. The hashtag #FreeHer is about all of us being free. We are there too,”

said Coleman, who is originally from Mississippi but is currently living in Florida. Her work is inspired by the challenges she herself faced as a formerly incarcerated trans person.

Ashunte Coleman

“When I came home from prison, I went back to the streets to do what I was doing before I was incarcerated. There were no programs so, I created one that helps trans women like me transition back into society. We currently serve about 20 women. We assist with stipends and referrals, and cover hotel costs for a few days because housing is one of the greatest challenges that trans women face when they come home.”

Inside prisons and jails inmates are assigned a number, a practice that contributes to dehumanizing people. One of the ways that members of the National Council remember incarcerated women is by stitching their names on colorful handmade “clemency” quilts.

The idea, inspired by the AIDS quilts of the 90s, is an effective way to capture individual stories and remind people that every incarcerated woman is a human being that deserves clemency. “The quilts show what is going on. People don’t know that many women are buried inside prisons,” says Sharon “BigShay” Smith, another founding member of the National Council who spent two years in a federal prison.

As an abolitionist organization, the National Council, seeks to end the incarceration of women and girls. The alternative to locking women and girls up, they say, is to reimagine communities.

For Metz, whose personal story is now a documentary film entitled Commuted, all communities must have access to public health services. Inspired by that notion, after coming home from prison, Metz earned a degree in addictive behaviors and counseling and is now a lead community health worker in her home state of Louisiana.

Read more: