Once a vast source of joy and enrichment and a crucial resource for communities in Jordan, the marshes of Azraq have dried up. Journalist Melissa Pawson meets Khadija, Karam, and Jad – three Azraq residents with bittersweet memories of the marshes as well as hope for the return of Jordan’s wetlands.

Find 7iber’s Arabic version of this article here. النسخة العربية من هذا المقال موجودة هنا على موقع حبر

Khadija Samdeh Shishani’s house sits beside a verdant oasis. The oasis is in a reserve next to Azraq town, located in the middle of Jordan’s expansive Eastern Desert. It is peaceful, quiet. Too quiet.

Before the 1990s, Shishani says that, during migration season, the sky would be bursting with birds, the air resounding with their calls.

“Across all of Azraq, ‘waa, waa, waa’,” Shishani says, mimicking the bird calls. “It was incredibly beautiful. I can still hear the sound in my memories.”

In the last 30 years, those skies have emptied and grown quiet. Most of the birds disappeared when the water disappeared, explains Shishani.

Khadija Samdeh Shishani said she learnt to swim in Azraq’s pools, and hopes that the water will come back one day – photo by Melissa Pawson.

Azraq, meaning “blue” in Arabic, was named for the colour of the town’s historic marshes, which were made up of two large pools and several seasonal pools. The marshes once stretched from Azraq castle to the current Azraq Wetland Reserve, an area of around six kilometres which was home to countless birds, fish, amphibians and water buffalo.

Residents used to swim, fish and wash their clothes in the fresh, glittering water. The pools were fed by several natural springs, and when the floods came at least once a year, the marshes would expand, and new pools and streams would appear. Those who still remember the marshes say it was like paradise on Earth.

Most of the site has now been reduced to dust.

When the water went, the community went with it

Photo by Mike Bishop via Flickr

Most of Azraq’s residents belong to three distinct communities. There are the Bedouins, a historically nomadic population who are thought to have roamed the Arabian Peninsula and Levant for thousands of years. Then there are the Chechens, a non-Arab Islamic population who were expelled from the Russian Empire and settled in Jordan under Ottoman rule at the beginning of the 20th century. And the Druze, a monotheistic group from across the Levant which historically lived between Syria and Jordan.

All three groups found themselves to be Jordanian citizens when the borders were drawn by the British and French authorities under the Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916.

Karam Tarabiah is from the Druze community. Sitting beneath a grapevine in his uncle’s garden, he explains his ancestors’ connection to Azraq.

Karam Tarabiah in his uncle’s garden. He said he remembers the very last of the marshes in Azraq – photo by Melissa Pawson.

“In the winter, they would walk from Jabal Druze [in Syria] to this area because it was warmer… They were coming here in the 1800s. So, when the border was drawn, the people who were already here became Jordanian,” he says. “If there was no water, they wouldn’t have come here. The water here is so important.”

The marshes from the 60s to 80s hanging on a wall in Azraq Lodge, near the wetlands – photo by Melissa Pawson.

Tarabiah, 40, was born during the marshes’ final chapter. “I remember the last of it,” he says. “But it started drying out before I was born. We saw it drying out with our own eyes.”

During the first decade of Tarabiah’s life, he says the pools got smaller and smaller. All the fish began to gather in the remaining deeper pools, where clean water still flowed. “The fish went to the spring,” he says. “Our family started going to fish in those pools because there were a lot there… They took the last of the fish and they sold them.”

While his family benefitted temporarily from the last abundance of fish, Tarabiah says that in the long term, their livelihoods suffered from the loss of the marshes. With no fish to sell, his grandfather only had his farm to rely on. The surface water of the marshes and streams had gone, and the groundwater was receding fast – so his well had to be dug deeper and deeper in order to irrigate his crops.

“His well was just four metres deep” says Tarabiah. “Now, that well is deeper than 80 metres.”

Just 10% of the original marshes are left, now concentrated in Azraq Wetland Reserve, which is fenced off and managed by the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature. The current wetlands are fed by fresh drinking water pumped in by the Jordan Water Authority, since the last natural spring stopped flowing in 1992.

Azraq Wetland Reserve – photo by Melissa Pawson.

The site remains a key stopover for migrating birds on their way to Europe, Asia and Africa, but numbers have plummeted in the last 40 years.

Read more: Climate change: IPCC report reveals how inequality makes impacts worse – and what to do about it

One of the main reasons for the loss of water in Azraq and across Jordan – one of the most water scarce countries in the world – is the excessive pumping of groundwater (freshwater present in layers of earth underground) since the 1980s.

The country’s population has grown steadily from around three million people in the 1980s to just over 11 million today. During that time, people from Kuwait, Palestine, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, Sudan and Syria have all sought refuge within Jordan’s borders. The country’s population rise has contributed to a rapidly increased need for water in industry, agriculture and for domestic use.

Shishani is from the Chechen community, and says that her siblings all moved away after the marshes dried up.

“Life was beautiful for us before. But they sold their land and went to the cities,” she says. “They went to live in Amman, Zarqa, and Irbid. They spread out.”

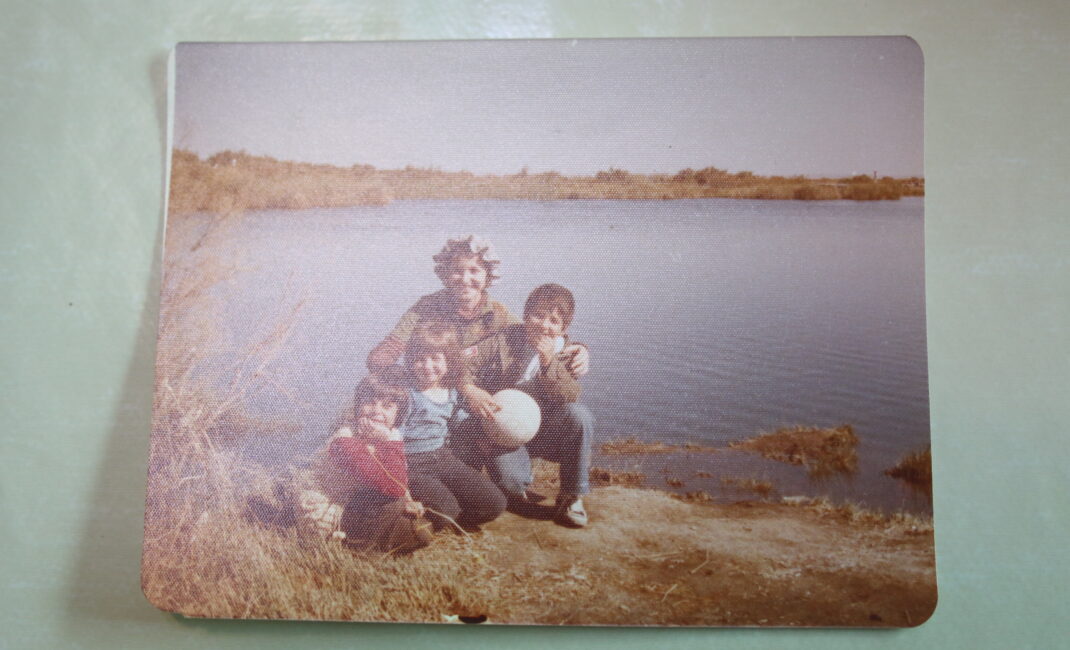

Shishani with her siblings by one of Azraq’s pools in the 1970s. (Used with permission from Khadija Samdeh Shishani)

She says she’s certain that they would have stayed, had the water remained.

“Life would’ve been much better here, of course,” she says. “We hope the water will come back one day.”

Shishani was born in Azraq in the late 1950s, to parents who had travelled to Jordan from Russia. She said the marshes were a community meeting point for the first 30 years of her life.

“That place would bring us together, and we would feel a warmth among us,” she says. “People would give and share and swap things. If I had buffalo cheese, I would give you cheese and you might give me homemade bread. We would eat together. It was so lovely.”

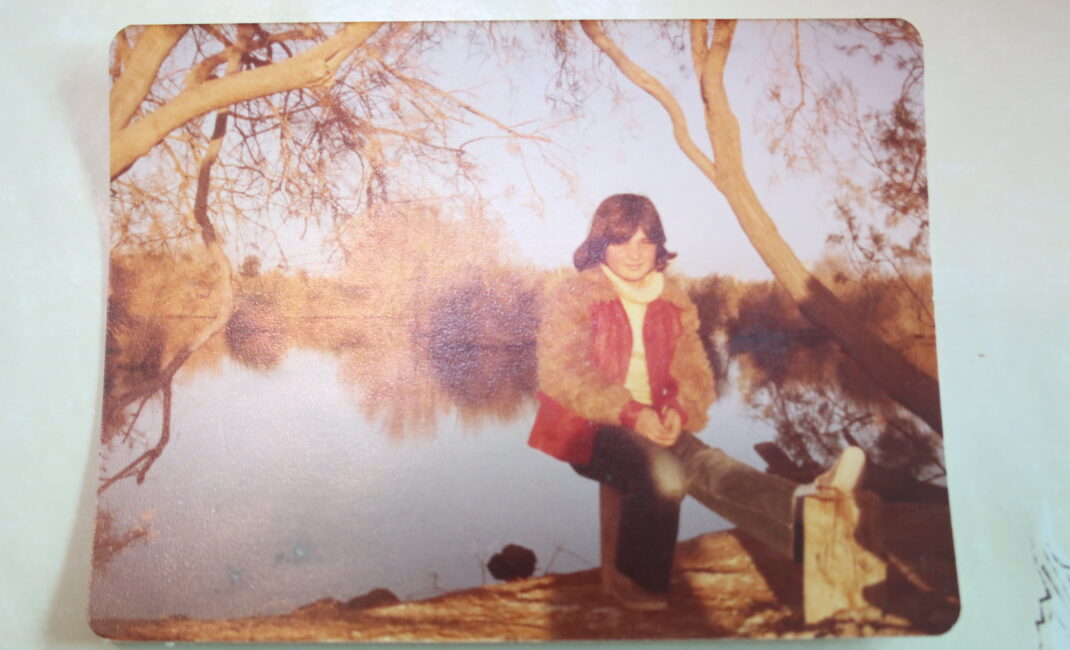

Shishani’s sister by one of Azraq’s pools in 1974. (Used with permission from Khadija Samdeh Shishani)

Shishani and her female friends could often be found swimming in the women’s pool in the marshes. “We lived in it,” she says. Laughing at the memory, she recounts the trouble that would ensue if any men came to spy on them or to fish there: “The big fish were in the women’s pool, but it was forbidden for the men to go there.”

Sometimes, young men would come to the pool to try their luck, says Shishani. But the women would shout and send them away, and then go and tell their brothers. The brothers would then go to the men’s families: “‘Your son was watching the girls while they were swimming!’”

The water buffalo, brought by the Chechens when they came to Jordan over a hundred years ago, were also central to their community traditions in Azraq.

“For weddings, we would tie the horns of the buffalo and give them as presents to the grooms,” Shishani recalls. “They knew their own names,” she said fondly of the buffalo.

A small population of buffalo remains, but they cannot live in the dry climate that has overtaken most of Azraq. Because of this, the buffalo now live in the wetland reserve, where they support the ecosystem and keep plants from overgrowing. Shishani says she misses them, and often goes to visit them. “If they don’t have water, the buffalo can’t live,” she says.

Shishani says the loss of the marshes has drastically impacted her sense of community. “Now, there’s a distance between people.”

Cracked earth at Shaumari Wildlife Reserve in the Azraq area – photo by Melissa Pawson.

Jad Alyounis was born in Azraq in 1960. From the Druze community, Alyounis says he too learnt to swim in the pools, and spent his childhood in the marshes. “Before school started, I would go down to the oasis and just watch the wildlife there… It was a paradise for me,” he says. “Some people tell me they used to catch me there naked there and bring me back to my mum,” he recalls.

“If I could show you what is in my mind’s eye, you would not believe how pure and clean the water was,” Alyounis says. “Streams running like a mirror, beautiful.”

Alyounis lived in Azraq until the late 1970s. In the late 1980s, he left Jordan for the UK, and returned for just a handful of visits over the next 24 years. He says when he came back in the early 2010s, he found the landscape entirely changed.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was a shock. To have seen it that way and to see it now, it’s literally a disaster. I was angry for what they have done. Horrible. It was just dust.”

Azraq has suffered from over three decades of intensive water extraction from its aquifer –one of 12 groundwater basins which are increasingly relied on to meet the country’s needs.

The aquifer is currently being pumped out to Amman and surrounding cities at more than twice its safe yield. This means the water is being extracted faster than it can be replenished, and will eventually run dry if pumping continues at the same rate.

In their 2023–2040 National Water Strategy, Jordan’s Ministry of Water and Irrigation notes that actual groundwater abstraction is estimated to be as much as 40% higher due to the illegal drilling of wells by farmers and residents. They also note that over half of all water resources are lost to “leakage and illegal use” across the country.

This paints a dire picture, with some studies predicting that 90% of Jordan’s low-income population will experience “critical water insecurity” by the end of the century.

Jad Alyounis said when he came back to Azraq after 24 years away, he was shocked at the disappearance of the marshes – photo by Melissa Pawson.

Could the marshes be brought back?

Like Alyounis and Shishani, Dawoud Iseid learnt to swim in Azraq’s marshes. He says this childhood inspired him to embark on his career as a hydrogeologist. He now works as an environmental consultant, and has worked on numerous governmental and NGO projects researching and monitoring water in Azraq.

He says he thinks it would be possible to recover the marshes in their entirety, but big changes would need to happen – not just in Azraq, but in Jordan and internationally.

Azraq Wetland Reserve – photo by Melissa Pawson.

Iseid says he believes the government’s water policies are too short term, and influenced more by politics than by science.

“There is enough water, but there is not enough management,” he says. Iseid adds that he is particularly worried about a new well field being drilled in the north of Azraq, which would mean “serious damage” for the area.

“They’re going to get water from the lowest point in the aquifer,” he says, explaining that this means saline water will start seeping into the freshwater layers, and could contaminate the water source. “I keep talking about it, but nobody listens,” he says.

But Iseid believes there are reasons to hope. “Instead of doing this, my proposal to the Ministry of Water is to do managed aquifer recharge sites,” he says. The recharge project would mean digging away the top layer of clay in a new or existing water pool, allowing some of that water to filter down through the more porous layers of earth and top up the groundwater beneath, before it evaporates from the surface.

Recent flooding has filled up some of the old pools in the mudflats. Residents say they haven’t seen flooding like this for thirty years. Behind it is the recharge pilot project overseen by the Ministry of Water – photo by Melissa Pawson.

Omar Salameh, spokesperson for Jordan’s Ministry of Water and Irrigation, says the ministry is “exploring the possibility of extracting 15 million cubic metres per year” from the new well field in the north of Azraq. He added that the ministry has a long-term plan to reduce the groundwater depletion “by regulating the drilling of unlicensed wells and preventing the drilling of illegal wells,” and that they are building new dams in the desert in order to increase the country’s water harvesting capacities.

But Iseid thinks the ministry needs to be doing much more recharging and much less pumping from the aquifer.

“The only solution for Jordan is to do small scale projects everywhere,” says Iseid. “Seriously, everywhere. Every drop matters… If we do [the full recharge project] in this area, around the mudflats, we will see the impact in around 5 to 10 years. You will start to see [water] seepage in the old springs.”

The effects of rare flooding in the last days of May can be seen across Azraq. Muddy pools cover the usually dry mudflats, and everyone is talking about the water, remembering when this used to be a regular occurrence.

Iseid says Azraq hasn’t seen this kind of flooding in 30 years. He says much of this water will evaporate, but could be used strategically to support the wetland reserve instead, for example.

Azraq Wetland Reserve – photo by Melissa Pawson.

For Shishani, the flooding has brought some hope. “The recent rains were so abundant, it was unbelievable.” she says. “If it rains a few more times like this, maybe the marshes will come back.”

She gestures around her house, glancing over at a collection of antique water collection pots, and then outside at the still empty sky. “Nothing is left of the past, other than my dreams,” she says.

Main image shows water in Azraq following recent flooding in the historical marsh area, raising hopes that the marshes might return – photo by Melissa Pawson.

Find 7iber’s Arabic version of this article here. النسخة العربية من هذا المقال موجودة هنا على موقع حبر

Read more: