In this touching story, Emma Tetsill outlines how the government failed care home residents like her grandad and suggests statistics distract from the real human stories of the pandemic. In light of the UK Covid-19 Public Inquiry and its assertion that ‘Every Story Matters’, Emma’s story is a sobering reminder of the tragic human cost of the pandemic and government neglect.

12 December 2020

“What do you want for Christmas, Grandad?” I ask, peering through the open crack in the care home window. I was within five feet of him, but the protective glass barrier obstructed any physical contact, ensuring we stayed ‘socially distanced’.

“A monkey up a stick” – his answer every year. I resorted to a Google search when I first heard him say it and found a vintage toy that literally is a wooden monkey twirling between two sticks. It encapsulated the selfless, immaterial, and content person he was.

“You’ve got one though. I bought you one last year!” He always asked for one and finally, I delivered. The smile on his face when he opened it is one of my most treasured memories of my grandad.

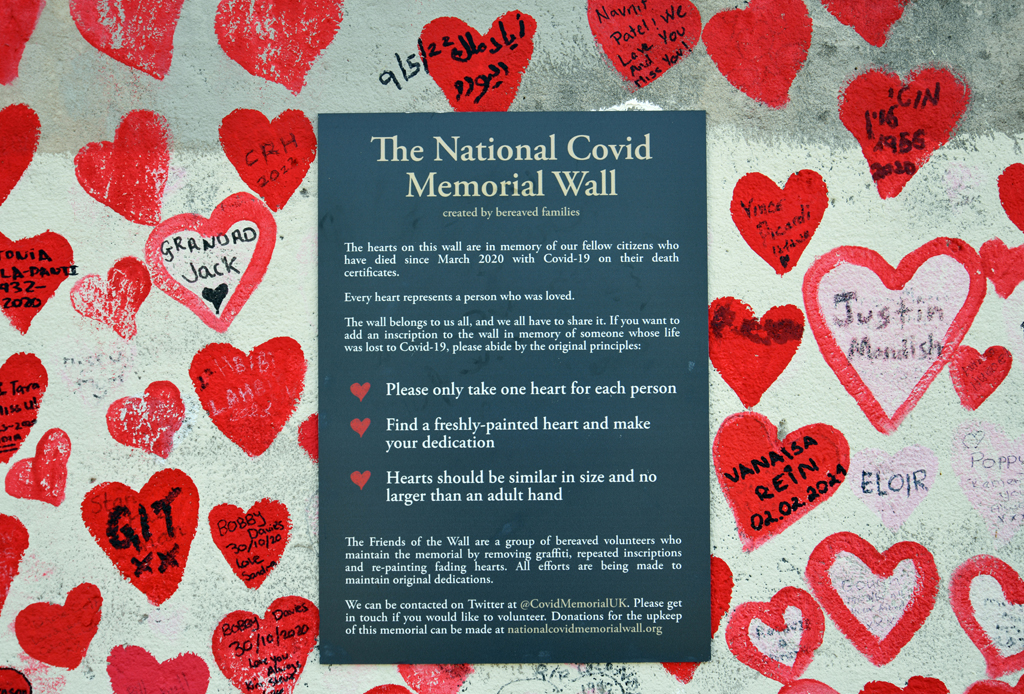

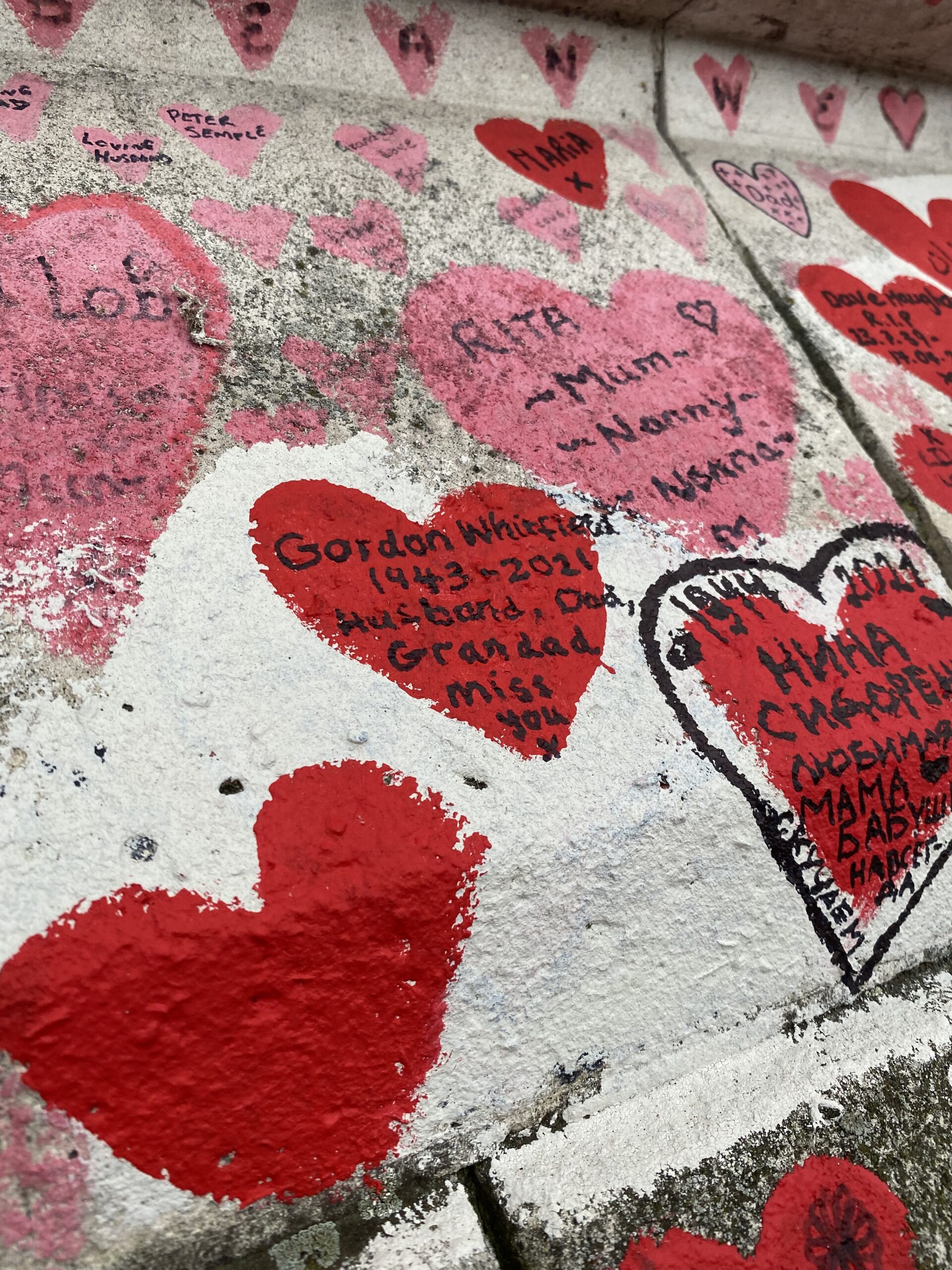

Gordon James Whitfield (1943-2021). I stare at my grandad’s name in fresh black ink on the National Covid Memorial Wall in London. A lump forms in my throat as his smiling face pops up in my memory – the face that lit up every time he saw us pulling up at his care home. I turn to my mom and see her wipe away a tear. Her dad. I pull her in for a hug.

My grandad was one of 1,350 people who died of Covid on the 21st of January 2021. He was a 77-year-old care home resident and had “underlying health conditions”– one of the many “vulnerable” people in the UK government’s eyes.

But he was so much more – a devoted husband, dad and grandad, whose ideal afternoon consisted of drinking tea, eating cheese and onion crisps, and watching the snooker. When he was living at home, he spent hours tending to his cucumber and tomato plants in his greenhouse and never missed a Saturday visit to the local tearoom. Yes, he had multiple sclerosis and was in a wheelchair, but in no way did this define who he was.

He was mentally the strongest person I have ever met, never put off from doing something that seemed out of his reach and never complaining about the pain he was undoubtedly in.

I was extremely close with my grandparents. Being from a small family, where my parents are both only children, at Christmas it was always just the eight of us (both sets of grandparents, my sister, mom, dad, and I) sat around the table. Sure, it was quieter than most, but I wouldn’t have had it any other way. My grandad and my nan would be at all my dance shows, on the other end of the phone congratulating me on every school achievement or wishing me luck for every upcoming exam and offering me all the chocolate in their treat cupboard every time I went to their house. I was blessed to have them both in my life.

As I grew older, of course, so did they and after my nan’s dementia diagnosis in September 2017, both my grandparents moved into a care home. My nan passed away in September 2019 and grandad continued to live at the care home without her.

Photo by Images George Rex via Flickr

When I first heard about Covid-19 in March 2020 and how it was more severely affecting older people, I began to worry about my grandad contracting the virus. Cases were spreading quickly, and care homes were very much becoming a hotspot, with people being discharged from hospitals and sent to care homes without being tested first. Luckily, the care home my grandad was in managed to avoid cases during the first wave of the pandemic, but it became clear that it was only a matter of time before that luck would run out.

On 2 December 2020 the Pfizer vaccine was approved in the UK. It was a huge day for the entire country, especially for families like ours who hadn’t been able to properly visit our relatives in care all year. Fitting in the top two “at risk” categories, we were confident that according to the government’s plan, grandad would be one of the first to receive his vaccine. Wanting to play a part in the vaccine rollout that was so fundamental to reconnecting our family, my mom signed up to be a vaccinator.

25 December 2020

“Merry Christmas, Grandad!” I exclaimed. He was waiting in his usual spot in front of the floor-to-ceiling window between the living room and car park.

“Merry Christmas to you too” he replied, beaming from ear to ear at the sight of us.

That smile.

“We wish you could come to ours for Christmas dinner, Grandad”

“Why can’t I?”

Grandad didn’t have dementia, but he struggled to grasp the concept of the pandemic and we had to remind him what was going on and why we couldn’t see him properly most times we visited. Grandad used to sleep most of the day and with the care home’s two TVs rarely showing the news, it was easy not to know what was going on in the outside world. I came away after seeing him each time with a sense of jealousy that he was completely unaware of what Covid was. I had to snap myself out of that. He had it far worse than we did in lockdown – he hadn’t seen his family for months, he hadn’t seen anyone for months, he couldn’t even leave the home.

“Mom has become a vaccinator Grandad, she’s going to help protect people so we can see you again”

“Is she?” A man of few words, but by his facial expression it was clear he welcomed the news.

“Yes, hopefully you’ll get yours really soon too!”

But it was January 14 before my grandad received his first dose of the vaccine. Six weeks after approval when he was in the highest priority group.

And tragically, it was too late. The luck had run out. On the afternoon of January 18, we had a call from the care home. My grandad had tested positive for Covid. He had been showing symptoms of what the nurses thought was a water infection, but a Covid test confirmed the worst. He had caught it from a carer.

Three days later, he passed away. It was all so quick and so cruel.

I take peace from the fact that Grandad didn’t really know what Covid was and so wasn’t scared of it. I take peace from the fact we were finally allowed to see him the day before he died, since the care home’s ban on visitors carried an exemption for the family of terminally ill residents. And that was what he was at this point, terminally ill. Covid took a swift hold on my grandad placing him in a deep sleep and so unable to take on any fluids, his passing was inevitable in those final 36 hours. He didn’t open his eyes during our visit and even if he had he might not have recognised us dressed head-to-toe in PPE, but we were there, by his side after months of our absence. I also take peace from the fact he is no longer in pain with his MS.

But what I can’t take peace with is the inequality of it all. Two years on, we are still left with burning questions: what if he’d had the vaccine sooner, what if care homes had been treated fairly, what if the government had really placed care home residents as a top priority? My family don’t know whether a first-dose vaccine would’ve saved Grandad – we never got to find out.

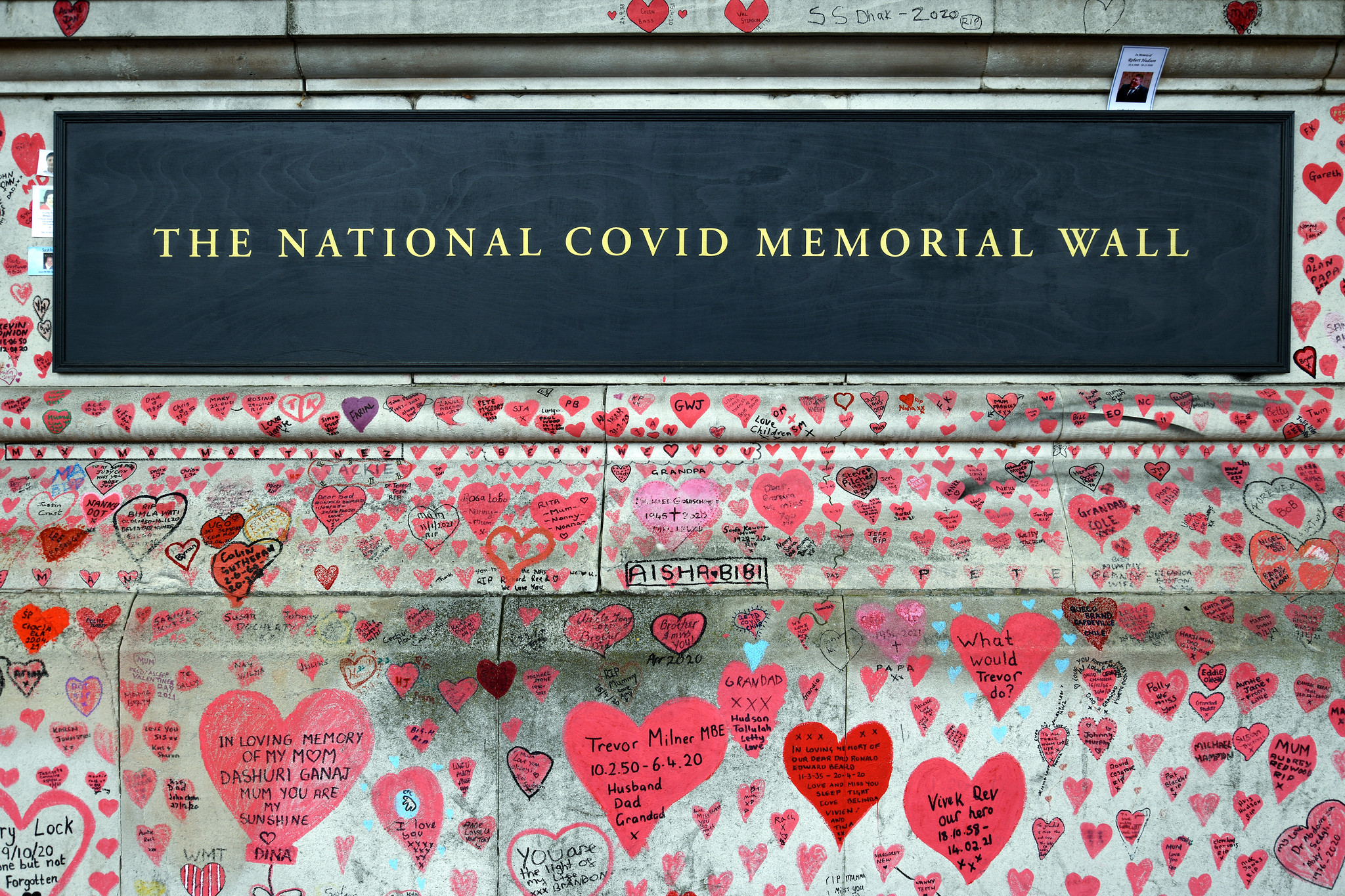

One red heart – one person – one story

Staring at my grandad’s name on the memorial wall, I take a step back and dozens of names stare at me, another step back and I see hundreds, then thousands of tributes along the wall each encased in a red hand-painted heart.

“Miss you Dad xxx”

“Love you Gerry xxx”

“My Nanny Kath love you forever”

The wall spans for a third of a mile on the Albert Embankment along the River Thames, positioned poignantly outside St Thomas’ hospital and ironically in the foreground of a vaccination centre.

There’s an aura here. A moment of serenity. You can hear the birds chirping and the wind filtering through the leaves of the trees that line the river. You would be forgiven for thinking you weren’t in central London.

There came the visual reality. We are not alone. My grandad is not alone. He is one of two hundred and twenty-five thousand, and eighty-one people. Two hundred and twenty-five thousand, and eighty-one people have died in the UK within 28 days of a positive Covid test. That’s the combined capacity of London’s Wembley Stadium and Manchester’s Etihad Stadium. Crowds of people – gone.

But a number is emotionless and can be too easily dismissed. We cannot see real people through a number. We cannot see the families who are left to grieve through the loss of a loved one, through a number.

As shocking as the statistics were to start with, death figures were soon just a slide on the government’s daily briefing. Or a number rolling across a news ticker.

There was little appreciation for the people behind these figures.

Yes, it was a way of coping at a time that was so abnormal from life as we had always known it. But the result was a dehumanisation of the lives we have lost.

What’s more, often deaths were reported with qualifiers that those who died had “underlying health conditions” or were over “70 years old”. Perhaps reporting deaths in this way offered a layer of protection for people who didn’t meet these characteristics, that they would be ok. I have heard all sorts over the past two years such as, “Covid is only severe for the elderly who will die soon anyway” or “old people die each year from the flu, what’s the difference?” and “we should just be getting on with our lives.”

But a life is a life. One is not more or less valuable than another. A 70-year-old may have had 30 years more to live that the virus has taken away from them. But this way of classifying vulnerability has, subconsciously or not, made us view lives differently as if some are more important than others.

Image by duncan cumming via Flickr

Care homes were failed

My grandad was a care home resident – a member of the most forgotten group during the pandemic. The extent of the pandemic’s impact on care home residents and staff go far beyond my grandad’s story. The Channel 4 drama ‘Help’ gives a sense of what care homes had to deal with, especially in the early days of Covid. A lack of PPE, a shortage of staff with many carers off with Covid themselves, and residents “de-prioritised” when it came to hospital admissions. But what makes care residents lives any less valuable or any less worthy of care?

Amnesty International have stated that ‘government decisions put tens of thousands of older people’s lives at risk and led to multiple violations of care home residents’ human rights.’ It is perhaps ironic then that the memorial wall sits directly across the Thames from the Houses of Parliament, staring over the water at the building where life-changing decisions were made.

Many insist the government did the best they could in difficult circumstances, while others say they were “grossly negligent”. Perhaps the findings of the Covid-19 Public Inquiry will reveal the truth. But in my family’s eyes, the biggest failure was the delay in getting care home residents and staff vaccinated. The care staff at my grandad’s home were left completely in the dark for the whole of December 2020 about the vaccination programme despite its approval at the start of that month. The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation emphasised from the vaccine’s approval date that those in care homes should be prioritised, but the government said this wouldn’t be possible straight away because the temperature the vaccine needed to be stored at made it difficult to transport. But surely the government knew this? Why wasn’t there already a plan in place to overcome the logistical hurdle of getting the vaccine into the arms of the most vulnerable?

The reality

Right now, our fight isn’t against the government, it is against the virus. It’s easy for those who haven’t been directly affected by Covid to be dismissive of it, thinking it’s not that serious and won’t affect them. I hope my story can serve as a reminder to do what you can to protect yourselves and your families.

This is my grandad’s story, but every person who has lost their life to Covid deserves to be remembered, not as a statistic, but for what they brought to the world. The memorial wall in London has restored some humanity to those statistics but not everyone has had the chance to see it for themselves.

So, the next time you hear a newsreader quote the Covid death toll, please take a moment to pause. There are real people behind those figures. Respect is the least they deserve.

Image by Images George Rex via Flickr

For my Grandad and Nanny Whitfield. I miss and love you both so much. Rest in peace x

Main image by Aurelien Guichard.

Read more: