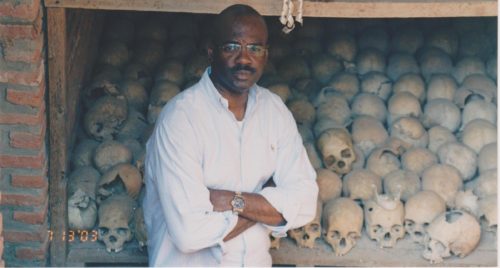

After the Rwandan genocide saw the murder of up to one million people, prosecutor Charles Adeogun-Phillips was tasked with delivering justice to the victims. Here he talks about his 12 years leading genocide prosecutions at the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, how he coped with the crimes he tried and what he learnt about humanity.

In 2001, at the age of 35, you were appointed senior trial attorney at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). Entrusted with the weighty responsibility of ensuring justice for the victims and dealing with deeply disturbing evidence, were you ever so overwhelmed that you felt like giving up?

Yes, but I made a conscious effort as a prosecutor to interact with the victims and witnesses and many a time I found myself championing the cause of those who had lost virtually all the members of their family.

So even though the humanity in me may have wanted to give up, or be fatigued from the sheer scale of work, the passion to champion the cause of victims of such heinous crimes kept me going.

Every time I went back to the beautiful Rwandan countryside, I would see my witnesses and people who would help us prove our cases before the courts. That encouraged me. You see, one of the drawbacks of the ICTR was that the trials were taking place so far away from where the crimes occurred. Many of our witnesses would be flown to Tanzania to come and testify, and they would be returned to Rwanda, and they were never able to follow up. So when they saw me, they’d ask: ‘Whatever happened to that defendant? Oh he was convicted! How many years did he get?! Twenty five years? Oh good!’ Just seeing them respond like that was very uplifting and that really energised me to forge ahead.

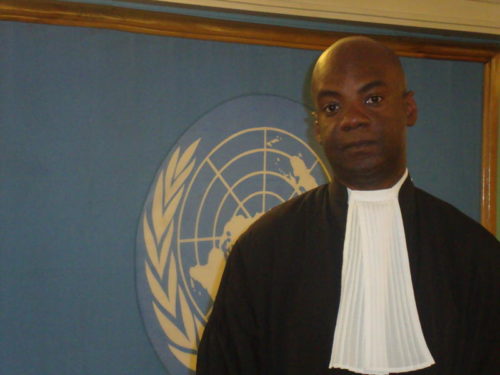

Charles Adeogun-Phillips at the Special Tribunal for Lebanon

What do the abhorrent stories of the Rwandan genocide tell us about the nature of humanity? And, having been immersed in these stories, how have you managed to come out the other side unscathed?

I’m not so sure I’ve come out of it unscathed. Clearly the events in Rwanda were the worst examples of man’s inhumanity to man. I did 12 trials in 12 years and for each one I had to give an opening speech. I remember a particular opening speech that I gave at the commencement of the Ntakirutimana joint trial in 2001, when I said:

‘I wonder what it is in a human being that sustains such frenzy? You know, to wake up in the morning with a machete in your hand and to go hack-hack-hack-hack for a hundred days back-to-back and to never stop and ask yourself ‘What am I doing?’

I just wonder, what is it that sustains such frenzy in a human being? Is it hatred? Is it incitement? What is it?’ And the answer we got from many of those who in later years pleaded guilty and came back to testify for us as insider witnesses was that, they were so convinced that they were doing the right thing at the time, based on the propaganda. How can you kill your neighbour you’ve lived with for so many years and believe you’re doing the right thing? Such was the nature of the direct and public incitement on the citizens of Rwanda.

And how did that affect you personally?

Anyone who visited the churches in Rwanda where some of these massacres took place and saw the corpses of men, women and children, twisted in pain, and lying in their hundreds beside the altars, will never forget those sights. Indeed there was so much in the human catastrophe that occurred in Rwanda that defied belief – parents betraying their children, doctors murdering patients and bishops and pastors taking part in the slaughter of their parishioners and members of their congregation.

It is no surprise that more Rwandans died in churches than anywhere else. The Church has always exalted the virtue of obedience, and many of the survivors who testified in some of my trials testified that many of the massacres happened because they blindly obeyed the authorities, regardless of who they were or how evil they were. A disturbingly large number of priests and pastors assisted the killers. They betrayed the hideouts of their Tutsi colleagues and refugees to the killers. They refused to provide a sanctuary for those who were hunted. Many of those responsible for the killings and desecration of churches were members of the congregation. The victims and survivors of these attacks testified as to their shock and bewilderment at the behaviour of people in whom they had trusted and thought of as ‘good Christians’.

The failure of the churches in Rwanda to take a collective stand against the genocide and the overwhelming evidence of the direct participation of many clergy in the massacres is one of the most disturbing aspects. I must admit that it tested my faith as a Christian.

I think many years later I realised that maybe I may have been damaged mentally or emotionally. But at the time, I really didn’t have time to think about it. I just plodded on with the work, and it was one trial after another trial, after another. But what was frightening was the resolve of some of the Hutus in exile, several years later, to come back to Rwanda. They were almost boasting that, ‘If I don’t go back, my children will go back and take over the country’. That worried me because I thought, several years later, where is the reconciliation in all this? Why are nerves still so frayed? When the first thing they say is that they can’t wait for the day when they go back and take revenge… Yeah, that worried me.

You had to speak with victims, and hear their stories. How did you maintain a professional distance?

Charles Adeogun-Phillips

Well, I had a challenge with one woman who had provided a statement to the effect that she wasa witness to the rape of six other women who were hiding with her during the genocide. Overcoming what was widely regarded as a ‘culture of silence’ amongst victims of rape or other forms of sexual violence was one of my major challenges as a genocide prosecutor. Culturally, African women are often reluctant to discuss matters pertaining to rape and other forms of sexual assault. Being a victim of rape or sexual assault and being part of a society that refuses to recognise you as such must be extremely hard. In this regard, I often found that many survivors of acts of rape were reluctant to testify about their experiences as victims of violence as they feel degraded and ashamed or fear they will suffer social ostracism from their husband and/or family if they disclose what has happened to them.

In the landmark trial of serial rapist, Mikaeli Muhimana, which I led before the UN genocide court in 2004, the woman had provided an extensive witness statement chronicling, in great detail, how she witnessed several Tutsi women who sought refuge along with her inside a hospital ward, being raped, before being killed with machetes. She only survived because she lay soaked in blood among several bodies, pretending to be dead. I wanted to meet with her in person and question her about some grey areas I had identified, prior to shortlisting her as a potential prosecution witness.

Speaking through my Tutsi female legal assistant who also doubled as my Kinyarwanda interpreter, I asked: ‘I can understand how you faked your death, but how were you able to survive not being raped by the defendant and his men?” In response, she said that she, too, had been raped but had left that out of her statement, firstly because she had been interviewed by a team of mostly male investigators, but, more importantly, because she had not mentioned the rape to the man she had later married, having lost her entire family during the genocide.

The woman offered to amend her witness statement to indicate the fact that she had been raped on the condition I guarantee that her husband would never become aware of the rape before, during or after her testimony. As much as I needed her testimony this was one undertaking I refused to give. To give it would have meant placing the future of an African woman who had avoided the stigmatisation of rape and managed to re-build her life in complete jeopardy. I wasn’t willing to shoulder such responsibility and I guess that’s a very clear example of when your humanity really overrides your status or standing as a prosecutor.

A drowned boy, an apology, an attack on ‘activist, left-wing human rights lawyers’

How does an ICTR prosecutor maintain a healthy balance between personal life and professional life?

With a lot of difficulty especially when you have a young family. It is however very important to learn to take time to switch off and focus on other things which you enjoy doing. The challenge is knowing when the time has come to do just that. This is because, international criminal trials can be very protracted as they can go on for several years.

The witnesses are numerous (the average case has 20 to 25). At the higher end, there are probably 90. You are also dealing with a maze of evidence and documentation. So even when you don’t hear it, you read it. You view it in pictures.

When you’re dealing with witnesses the wounds are still there. You see the slashes on their foreheads, you see the cuts there, you see the one who’s lost a limb, and you’re confronted with it.

You’re not only hearing a story, but you’re actually seeing the injuries. And sometimes you just have to shut down at the end of the day.

I became an international prosecutor at 31, I had been married for just over 18 months and my family was very young and my children literally grew up on the job. My first, my eldest son, was six months old when I started doing this work, and his two sisters were born on the job. You need to be able to shut down when you leave the office and remind yourself that you have loving children at home to go back to. But on the other hand, you almost feel guilty that they are so well clothed and that they have security around them because you’ve just been talking to a woman who was unable to protect her own children, through no fault of her own. You transcend those emotions. There’s guilt, anger sometimes, but you know you have to stay focused and get the job done.

After the trials ended, you later had the opportunity to find out more about the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). What do you think about a report by Human Rights Watch that claims the unwillingness to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the RPF is one of the ICTR’s main weaknesses?

Yes, there are allegations of atrocities committed by the RPF. I was appointed as Head of Special Investigations and I was looking at what the other side had done. It is clearly a failing of that institution.

But I’ve come to realise that, in practical terms, there is, whether you like it or not, an apparent conflict between the need for peace and the need for justice. Those two things don’t necessarily work together, even though people like to pretend they do. The reality of it is that you have to give up one for the other.

We could see this in Liberia and we’ve seen it in other jurisdictions. I guess the sense of the international community is that you can’t pursue both at the same time. Rwanda has taken great strides in economic and social development and I don’t think anyone is interested in ruffling feathers. I personally was disappointed that we weren’t able to do it ourselves in the face of the evidence that we clearly had. I thought maybe we should have done one or two sample cases to be fair because there were allegations on both sides.

Criminal justice demands a balance of the rights of the accused, the rights of the prosecution, and the rights of the victim. How can international criminal law maintain this balance?

Charles Adeogun-Phillips

That is actually a huge challenge. Unlike ad hoc tribunals, where the victims didn’t have a role, at the ICC victims actually have a voice, and that is important. But I think the jurisprudence of the ad hoc tribunals have gone to great lengths in upholding fair trial rights of defendants. Some of the defendants in these ad hoc tribunals get away with murder in the sense that they have a right to representation even when they cannot afford it. I think the international criminal tribunals are clearly the best examples of the guarantee of fair trial rights of accused persons. The trials are slow because they are complex, and people have argued that the length of time, and the length of pre-trial detention in some cases, have affected the fair trial rights of the defendants. But if you understand the complexities of international criminal trials being conducted far away from the original crime scene you then realise that a length of pre-trial detention of a year or a year-and-a-half is not actually unreasonable in the context of those cases. They are very complex trials.

Alleged war criminals facing trial are often very rich people, able to pay large sums of money to lobbyists who campaign in their favour. Due to the influence of these lobbyists, such alleged perpetrators are sometimes presented to the world as victims of miscarriages of justice. How do you feel about the role played by lobbyists?

It’s true that the perpetrators are drawn from higher echelons of society with access to a lot of resources. But the other point is that the crimes themselves are not seen by the perpetrators as crimes but as the result of political squabbles and differences. We saw that from many of our defendants at the ICTR who put up all sorts defences to genocide. They never saw it as genocide in that sense, it was ‘us against them’, a political difference that got out of hand.

As long as the main actors in this sort of crime are drawn from the higher echelons of society lobbyists will always have some role to play. We saw it in South Africa with the Gupta family and one of the biggest PR firms in London being hired to put a spin on things. That can only work in borderline cases. In other cases the crimes are so heinous that no amount of lobbying is going to absolve them. But political indifference is just as influential as lobbying. Look at Sudan, where the international community has paid only lip service to justice and accountability for heinous crimes. Nothing really comes of referrals to the Security Council. The usual phrase is: ‘Member States are encouraged to co-operate with the International Criminal Court’. That’s where it ends. The major drawback of these tribunals is their lack of law enforcement powers and the fact that they depend almost exclusively on the co-operation of the international community to be able to get anything done, even just to get access to a territory. I think that really is what must be addressed and that’s another reason I would opt for domesticated trials.

For societies that are victims to the most egregious crimes what is the solution? Prosecution? Or amnesties leading to reconciliation? And also, do you think state representatives like presidents and prime ministers possess the moral right to grant amnesties in the first place?

The Gacaca system of justice that was introduced in Rwanda in response to the sheer number of perpetrators involved in the genocide is still one of the most impactful experiments in terms of domestic answers to widespread international crimes. I don’t think it has been replicated anywhere. That’s one positive story out of Africa. Another is the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa where Madiba Mandela had decided that he wasn’t going to take the prosecution route but rather have a truth and reconciliation commission, which worked in those circumstances and was tremendously successful. There have been so many experiments that have been deployed from full international ad hoc tribunals to hybrid tribunals in Sierra Leone where there has been a mixture of local and national jurisdictions, in East Timor as well and in Cambodia to a permanent international court. The future of international criminal law lies in strengthening domestic jurisdictions to be able to take on these cases, for the simple reason that you can build local capacity. The problem with doing it ‘internationally’ is that you go out and you build the capacity in the Hague, or in London, but you don’t build the capacity in the country where the crimes occurred, which is really where it’s needed. You need to build the capacity of judges, prosecutors, defence counsel, victim support, etc. So I am all for domestication of cases involving international crimes with the sole view of actually aiding reconciliation, because justice is not only done but it’s seen to be done. That was the drawback in Rwanda. We were sitting so many miles away from Rwanda, the average victim didn’t actually know what was going on. So domesticating trials ensures that justice is done and is seen to be done, aiding reconciliation but more importantly building local capacity and building the local jurisprudence. That should be the future of international criminal justice.

Having studied at Warwick University and then SOAS, how did you train yourself for the ICTR?

The most fascinating aspect of this work was that there was no precedent to go by. None whatsoever. So we literally built the body of law known today as ‘international criminal law’.

The last war crimes tribunals were the Nuremberg trials and we initially tried to replicate Nuremberg by having 28 accused persons charged in one indictment. We very quickly realised that it was impracticable. Where do you put 28 people in the courtroom, let alone their own counsel and co-counsel? The elements of the crimes and the participation were not like the Nuremberg cases where the elements were the same and the perpetrators acted in concert.

We had to build this area of law, both substantive and procedural. The issue of sexual consent, for example, was rendered immaterial where women were seeking refuge because when the circumstances are so coercive you can’t talk about a woman consenting. She’s seeking refuge from her captor and she’s being raped every day by the man who provides her with refuge. Things like witness protection measures and the use of pseudonyms were all novel to this area and are still in existence to this day. So being part of building that whole body of law was very fascinating and a great privilege.

Can you describe a time when emotions were running high and the atmosphere in the courtroom became heated? How did you handle situations like that?

I was leading a rape victim through her evidence before the tribunal in the Mika Muhimana case. And there was a panel of three judges: Judge Rachid Khan from Pakistan, Judge Lee Muthoga from Kenya, and, I think, Judge Emile Short from Ghana. And whilst I was leading this witness she was explaining how she had been raped and the circumstances and trying to describe the room and how things happened. The suspect, the accused, was sitting in the courtroom and the victim was being confronted by this man. So I had to be very gentle in leading her through it. And one of the judges, one of the male judges,became impatient. He turned on his microphone and said: “Look witness, what the prosecutor is trying to find out from you is, where did the action take place?!”

I stood very quietly and let him finish and turn off his microphone. I then said: ‘I accept, My Lord Your Honour that you’re trying to be helpful but I certainly see nothing ‘actionable’ about a rape and I really would not like to describe what happened to this witness as the ‘action’. So if you’ll just be patient and allow me,I will guide this witness through her testimony, difficult as it may be asshe’s being confronted right here by the man who raped her. I am deliberately going slowly and easing her into the conversationbut please be patient.’ Of course, in his own mind, he was being helpful to me in trying to help the witness get through her testimony as quickly as she could. But his choice of words was most unfortunate for a woman who had been through such a heinous crime.

The biggest challenge of prosecuting widespread and heinous crimes like this is that you’re making the witnesses or the victims relive their experiences several years after – experiences they would rather forget.

So when a woman is sitting in a courtroom with a man who raped her serially, the last thing you want is to be insensitive to her plight.

After the ICTR, you moved on to commercial litigation – two polar legal environments. How did you make that transition and how should a lawyer prepare to make a similar jump?

War crimes areso unique that you couldn’t make a living out of being a war crimes prosecutor -and for good reason. They are the worst crimes known to mankind. My interest in commercial litigation came purely by accident. I was retained by the government to help recover assets from failed banks and chronic debtors. But interestingly, there was a criminal law aspect to it, because right from the time those loans were given there was never any intention to pay them back. So we advised the government to move from looking at these matters as ‘bank-customer relationships’ that had gone sour to actually building criminal cases out of them. And because of my background in international criminal law, I was able to build white-collar criminal cases from what would otherwise have been normal banking commercial transactions. My experience at the international court has enabled me to do a lot of things and dealing with lawyers from all over the world has enabled me to use those connections to trace and recover assets for my government.

Below Adeogun-Phillips speaks with the Wayamo Foundation about the challenges African states face in prosecuting international crimes.

Main image of Kigali, Rwanda, by Maxime Niyomwungeri

- For content like this direct to your inbox subscribe to our monthly newsletter.