The story of one woman, Rahil Azizi, highlights the impossible situation of Afghan refugees and asylum seekers seeking safety in Pakistan. Azizi’s long fight to claim asylum through the Islamabad High Court suggests there is an ever-widening gap in Pakistan between the letter and the spirit of the law. Arjumand Bano Kazmi believes Azizi’s victory could be a timely aid to hundreds of other Afghan refugees who are subjected to arbitrary arrests, detentions, trials and deportation.

When the US and its allied forces withdrew from Kabul in 2021, Rahil Azizi, an Afghan national, fled her home country fearing for her life. Before this, Azizi, had spent five years working for the Afghan Police. But when the Afghan government collapsed and the Taliban took control, many Afghans who had been associated in any way with the outgoing regime feared persecution.

Azizi was just one among an exodus of Afghan nationals who became refugees overnight. Since then, thousands have left for Pakistan – some with visas, others without.

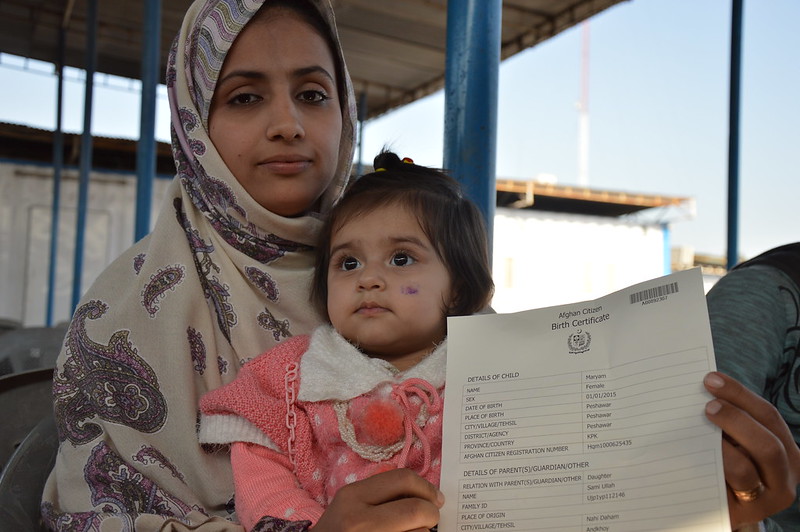

An Afghan refugee in Pakistan registers her daughter to appear on UNHCR’s database and get a birth certificate – European Union/ECHO/Pierre Prakash

Azizi had neither the hope nor time to obtain a visa from the Taliban authorities before she fled. Once in Pakistan, she approached the police in Islamabad and voluntarily disclosed herself as an Afghan refugee without a visa. Azizi was initially sent to a government-administered shelter for women but was subsequently arrested for an offence under Section 14(2) of the Foreigners Act 1946, which states:

“Where any person knowingly enters into Pakistan illegally, he shall be guilty of an offence under this Act and shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to ten years and fine which may extend to ten thousand rupees.”

Azizi was sent to Adiala Jail as an under-trial prisoner. Her bail applications were rejected on two occasions by the lower courts. However, upon appeal, she was granted bail by the Islamabad High Court (IHC). Whilst in custody, Azizi sought support from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Pakistan and was given an Asylum Seeker Certificate confirming not only that she is a legitimate applicant for asylum status but also that her case was being considered for refugee status. Following this, Azizi was granted a ‘Humanitarian Woman at Risk’ visa by Australia.

But when she sought an exit permit to leave Pakistan she was denied by the Ministry of Interior, which claimed that a permit could not be issued to a person under trial.

The Ministry took issue with the fact that Azizi was granted an Asylum Seeker Certificate two months after her arrest, claiming that such a certificate could not be applied retrospectively to legalise Azizi’s entry into Pakistan without a visa. As an accused person under trial, Azizi could not be allowed to leave Pakistan. She spent nine months in prison.

Now, however, Azizi has won a long-awaited reprieve. Delivering its judgment in June this year, the Islamabad High Court stated: “The law is not meant to act a trap”.

Azizi’s victory can be considered a milestone in the judicial history of Pakistan, a country which is hosting one of the largest refugee populations in the world and is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention or to the 1967 Protocol.

The judgment is not only a victory for Rahil Azizi, but may also be a timely aid to hundreds of other Afghan refugees in Pakistan who are being subjected to arbitrary arrests, detentions, trials, and deportation to Afghanistan in large numbers, charged with illegal entry and stay. The precarity experienced by Afghans seeking refuge in Pakistan has risen alarmingly in the last year with many of them having to hide for the fear of police arrest, losing the opportunity to work and consequently spiraling into poverty. Earlier in October, the current caretaker government announced plans to deport all ‘illegal’ Afghans to Afghanistan by November 1.

But to build on Azizi’s victory, we need to understand how the IHC ruled in her favour.

The letter and the spirit of the law…

In the absence of any international or domestic legislation, which deals with the governance of refugees and asylum seekers in Pakistan, the judgment marshals a number of arguments to substantiate the decision. To understand the legal framework of granting asylum status in Pakistan, the IHC considered various sources including: the agreements between the Government of Pakistan, Government of Afghanistan and the UNHCR, signed in the 1990s and extended post-2010; The Constitution of Pakistan which guarantees the right to liberty as well as the right to dignity of every person who, for the time being, is in Pakistan; and the obligations under international laws that Pakistan is a signatory to, including the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights 1966 ICCPR) and the Convention Against Torture 1984 (CAT) requiring Pakistan to observe the principle of non-refoulement (not forcing refugees back to the country they fled), also enshrined in Article 33 of The Refugee Convention 1951 and generally considered as a customary international law.

Afghan refugee women in north-west Pakistan – UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe

However, the argument which shifted the decision in Azizi’s favour was based on a critical engagement with the Section 14(2) of the Foreigners Act that constitutes an act of entry as a criminal offence “if there’s a ‘guilty intent’ or mens rea on part of an accused”. Azizi successfully pleaded that she was seeking refuge to protect her life and did not have any criminal intent with which she entered in Pakistan. Her disclosure upon arrival to the police in Pakistan was the proof of that.

The Court stated:

“Just because there is no statutory or policy mechanism available to a foreigner to disclose to the State of Pakistan at the time of entry that he/she has entered to seek refuge and save their lives and to apply for asylum in accordance with principles of international law, does not mean that Section 14-B will come into place automatically to penalize such foreigner.”

“The law is not meant to act a trap. …. That Pakistan does not have its own legal framework for refugees does not mean that anyone seeking refuge out of fear for his/her life or liberty must do so at the cost of being imprisoned….”

Article 31 of the 1951 Refugee Convention also makes a key reference in the judgment, advising the government that the UNHCR-registered refugees must not be kept incarcerated like prisoners under trial. Azizi is now permitted to travel to Australia. But how can her victory be used to support others?

A landmark judgment?

The IHC judgment on Azizi’s case highlights a dilemma of determining someone’s status either as a refugee or an “illegal immigrant” and reveals the restrictive and rather regressive reading of the existing law which is usually applied to Afghan migrants and refugees entering and/or staying in Pakistan.

Since November 2022, a score of Afghan migrants, in similar conditions to Azizi, have been subjected to arbitrary arrests, detentions, trials, and deportation to Afghanistan. Those arrested include Afghans who have been sheltering in Pakistan for years and others who have recently sought refuge post-2021.

Many were charged with illegal entry or stay under the Foreigners Act 1946. Recent arrests have taken place in Karachi, in Sindh province. Since September, over 1,700 Afghan refugees living in Karachi were reported to have been arrested.

The Governor of Sindh, Kamran Tessori, approved of the arrests saying: “The government has directed law enforcement agencies to arrest Afghans living illegally in Sindh and elsewhere in the country.”

Reports of arrests from other parts of Pakistan have also emerged with approximately 600 Afghan refugees arrested in Islamabad and hundreds more in Balochistan. The arrests were defended by the Caretaker Prime Minister of Pakistan, Anwaarul Haq Kakar, who has asserted: “We will push the (Afghan) aliens back to their country and no one without the visa regime, will be allowed to live here.”

Afghan refugees in Quetta, Pakistan, who live outside of the formal system of refugee camps – UN Photo/Luke Powell

The sad reality is that such a crackdown on Afghan refugees is not new. From time to time, there have been waves of arrests and detentions, which have made the lives of Afghan refugees in Pakistan insecure and destitute. Recently, this is not only being done to Afghans with no proof of entry or stay in Pakistan, but also to hundreds of Afghan refugees who hold one or another form of verified identity i.e. Proof of Registration (POR) cards issued by the UNHCR, or the Afghan Citizens Cards (ACC) issued by the Government of Pakistan, or the holding certificates of asylum provided by the UNHCR.

It is true that these identity cards or certificates issued to Afghan refugees, in some cases, may have been expired, but this is due to no fault of their own. In recent years, updating and extending these cards has proved a huge administrative challenge for the government, leading the Ministry of States and Frontier Regions (SAFRON) to issue a public order demanding that police should not harass or arrest Afghans on this basis. Such an order was issued on 20 June, 2023.

However, despite this, the arrests, detentions and deportations have continued. The (HRCP) Human Rights Commission of Pakistan and Amnesty International, among several other human rights groups, have issued statements in support of vulnerable Afghans and have urged the government to consider signing the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol. HRCP has also called on the government to reverse its recent decision to deport ‘illegal’ Afghans and to respect its obligations under international human rights law.

What does the future hold for Afghan refugees in Pakistan?

The difficulties Afghan refugees are facing in Pakistan suggest there is an ever-widening gap between the letter and spirit of the law, as limited as it is, in the absence of a national or international legal framework. Even the simple directive issued by the Ministry of SAFRON, is not being adhered to. What resides in this gap is political interest.

Afghan refugees and migrants have forever been treated as political pawns in the hands of Pakistan’s sitting governments and army. In the last 43 years, Afghan refugees have been welcomed as Muhajirs and Mujahids against the Soviets during the 1980s and they have been deported and/or voluntarily repatriated to Afghanistan in various phases depending on how amiable or not Pakistan-Afghanistan bilateral relations were, and how much support Pakistan was able to negotiate from international donors to host and manage Afghan refugees inside its territory.

Human rights groups have also observed that the various phases of voluntary repatriation of Afghans from Pakistan have not actually been voluntary; many were pressured to leave Pakistan by their living conditions being made untenable and insecure. An environment of fear and hostility is often created to force many Afghan refugees out. According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), many Afghan refugees signed up for repatriation not because they thought it was safe to return, but because they believed they had no choice in the matter. And since repatriation must be a voluntary choice, many who choose not to return to Afghanistan, have an ambiguous legal status and therefore are at a greater risk of harassment and arrest.

Afghan refugees in Pakistan – by Gretchen Alther for Unitarian Universalist Service Committee

There has been a historical narrative of anti-Afghan hostility amongst ‘settled’ Pakistani communities. On various occasions, Afghan refugees have been labelled as dangerous foreigners who bring risk and insecurity to Pakistan. This narrative is periodically repeated as and when politics necessitates. However, there’s sufficient evidence to suggest that most of the Afghan migrants are vulnerable refugees looking for safety from persecution and protection from the harsh living conditions in their perpetually war-affected homeland.

Politics aside, the management of refugees is an administrative challenge for Pakistan, a country struggling to balance its economic priorities, threats to internal security, and international humanitarian obligations. According to UNHCR, Pakistan is currently hosting 3.7 million Afghan refugees, of whom 1.33 million are registered with the UNHCR and possess Proof of Registration (POR) cards as their refugee identity; 840,000 hold Afghan Citizen Cards (ACCs) issued by the Government of Pakistan; 775,000 are undocumented; and 600,000 are the new arrivals since the withdrawal of the US and its allied forces from Afghanistan in August 2021. The unofficial figures suggest an even greater number of Afghans living in Pakistan in all these categories.

Where there’s a will….

The scope of the challenge is enormous and multi-layered. It requires a solution that is political, administrative, and legal. But perhaps making small tangible changes would be a start. What is plausible is for the law to chart a process-oriented pathway to help address the sufferings of thousands of Afghan refugees currently sheltering in Pakistan. The IHC judgment on Rahil Azizi’s case is a step in this direction. But Pakistan should also consider The Citizenship Act of Pakistan 1951 where there’s a possibility of granting citizenship to Afghans born in Pakistan.

Last but by no means least, a national legal framework on governing refugees and asylum seekers is a much-awaited development for which there’s a National Refugee Bill pending discussion in the National Assembly of Pakistan. The National Refugee Bill 2023 was introduced in parliament in March as a Private Members Bill by Mohsin Dawar, Member National Assembly and The Chairman of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs. The Bill calls for recognition of the right to seek and enjoy refugee status in Pakistan and to regulate the legal status of refugees.

Changing the politics of refugee governance in Pakistan is likely to take time. But judgments such as Azizi’s, make the courts a significant site where the refugee law could be developed domestically yet informed by the international norms of refugee protection. To date, the principle of non-refoulement as the principle of customary international law, and enshrined in the ICCPR and CAT, has been the key source for case law on refugees. Azizi’s landmark judgment, saw Pakistan engage with the Article 31 of The 1951 Refugee Convention for the first time. This shows how, incorporating the principles of The Refugee Convention, a generous and considerate reading of the Foreigners Act of 1946 is possible – as is a fairer and brighter future for Afghan refugees in Pakistan.

Main image: An Afghan refugee in Pakistan hands over her Proof of Registration card – European Union/ECHO/Pierre Prakash.

This piece was co-published with Dawn, whose version of the article can be found here.

Read more: