In this captivating narrative about her family fleeing Afghanistan, Wajma Zazai illustrates the plight of Afghan refugees then and now. This poetic story is a sobering reminder of the effects of conflict, not only on those living in it, but on those in the diaspora who are forced to watch what’s happening to their homeland through TV and phone screens.

This piece of creative fiction was originally written as a response to one of the themes of the Writing Human Rights module at the University of Warwick. The module confronts human rights themes and develops creative responses to them in writing. Students have free rein to choose the topic and style of their stories. They have written pieces of journalism, short fictional stories, sci-fi, screenplays, comment pieces, podcast episodes and TED talks. We have worked with students to develop the best examples of their writing and publish them on Lacuna (find them here). Wajma Zazai wrote this piece after the Taliban took control of Kabul in 2021. Wajma graduated from Warwick Law School and was awarded the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge Scholarship from the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple to support her Bar Vocational Studies at City, University of London. During her time at university, she volunteered to support newly arrived refugees, supplying donated books, clothes and toys.

What’s it like?

How much free space is there in your mind? How is it waking up clear and level-headed? Do your parents laugh?

Do you pay attention to the road whilst you drive or does your mind drift? Do you avoid the news, your phone, your regular TV channels?

Are you wandering through life or are you present?

Is your heart in your body or a place you may never see again?

Mother’s memories of Afghanistan

I have only felt this kind of sadness at funerals. An abundance of sadness accompanied by manufactured comfort; it’s sickening that I am unable to do anything.

I raise my hand up, I raise our flag and speak for us, to you, to the non-Afghans to feel an ounce of our gut-wrenching sadness, yet I am faced with a deafening silence.

Is this even enough? It’s your brave stories, Madar Jan, that inspire and ground me, to learn of our history, pain and people…to feel closer to my motherland. Sarzaminé man (my land).

“Madar Jan bogo,” I sat there with my notebook and pen asking my mother to “tell”.

Anxiously staring into her cup of green tea, she replied, “Az guja shoro konam zootar”. All I could see was a face full of despair, drained to tell, again and again.

Her response was “where should I even start from…” since there was too much. Too much to recall, too much to feel.

She was only 18 when the rocket came crashing down into their neighbourhood. The blast shattered every window in what was once her home.

Read more: Fleeing Palestine – and what happened next

“I felt the tremors within me for the rest of my life. Your aunties and I would hide in the corridors, as even the space between the four walls of the rooms felt unsafe. We held the Holy Quran to our chest and hoped there was a way out. All I wanted was to continue being a teacher, but those thieves, those hypocrite thieves, stole all of our hopes and dreams”.

When I asked her how she managed to flee the horrors, she uttered, “It took too much hiding to even get to the right people. I don’t know who they were, but they managed to get us behind their lorries. They told your father and I to stay patient when we would arrive because it was only a transit flight to London, and we could end up anywhere.

“That stupid word ‘patient’, it’s all we heard in Afghanistan. We had been dipping expired naan bread in water as meals for too long. I became accustomed to its crackling noise and stale scent as we shared it amongst ourselves.

“I will never forget the rough turbulence on the plane, it shook the cabin with no remorse. Twisting and turning, I endured the turmoil, remembering your grandmother’s words: “Sabr (patience), in this world as an Afghan woman you must patiently endure.”

Disheartened by the memories, she continued, “There was no future left. They stole our future, but we hoped to begin a new one, somewhere in another land where the birds flew freely, and the women weren’t caged. Where children could run, laugh and be raised in peace.

“We arrived at Gatwick with your brother, three months old, crying in my arms. Your other brother was two years old, asking constantly, ‘Madar Jan, when are we going home?’ The truth was I didn’t know, I didn’t know where home even was, whether I would ever find one, I didn’t even know where the money for their milk would come from”.

When I asked her how they were treated once they arrived, she replied, “We were desperate. I thought someone may have been able to help us, but the officer said we had gone past Immigration and we had to leave the airport. I cried in fear, pleading for help but the officers and the airport staff sternly told us to leave.

“We were told to find our own way and get to the Home Office. Were we any less human to be spoken to so harshly? That was the night I knew this would be a very long few years trying to find our way to safety and security. Turbulence had become a part of our life now, wherever we went.”

Listening to my mother’s anecdotes, I was in awe of her bravery. I knew my land was full of courageous women, but to be birthed by one was a different feeling.

The awe was followed by a feeling of guilty inadequacy of the privileges I have been gifted and taken for granted.

A new generation leaves Kabul

I opened my laptop screen to see an email from Warwickshire County Council. It read: “Hi, Wajma. We have new information from the Home Office. We will be expecting 100 families to arrive at their accommodation on Monday…”

Before I could finish reading the email, I felt a sudden emptiness, sick to my stomach that history had repeated itself. These people were leaving Kabul but what about the others who still live their lives in fear? Days dragged by and time grabbed hold of our lives with its bare hands, stifling every breath.

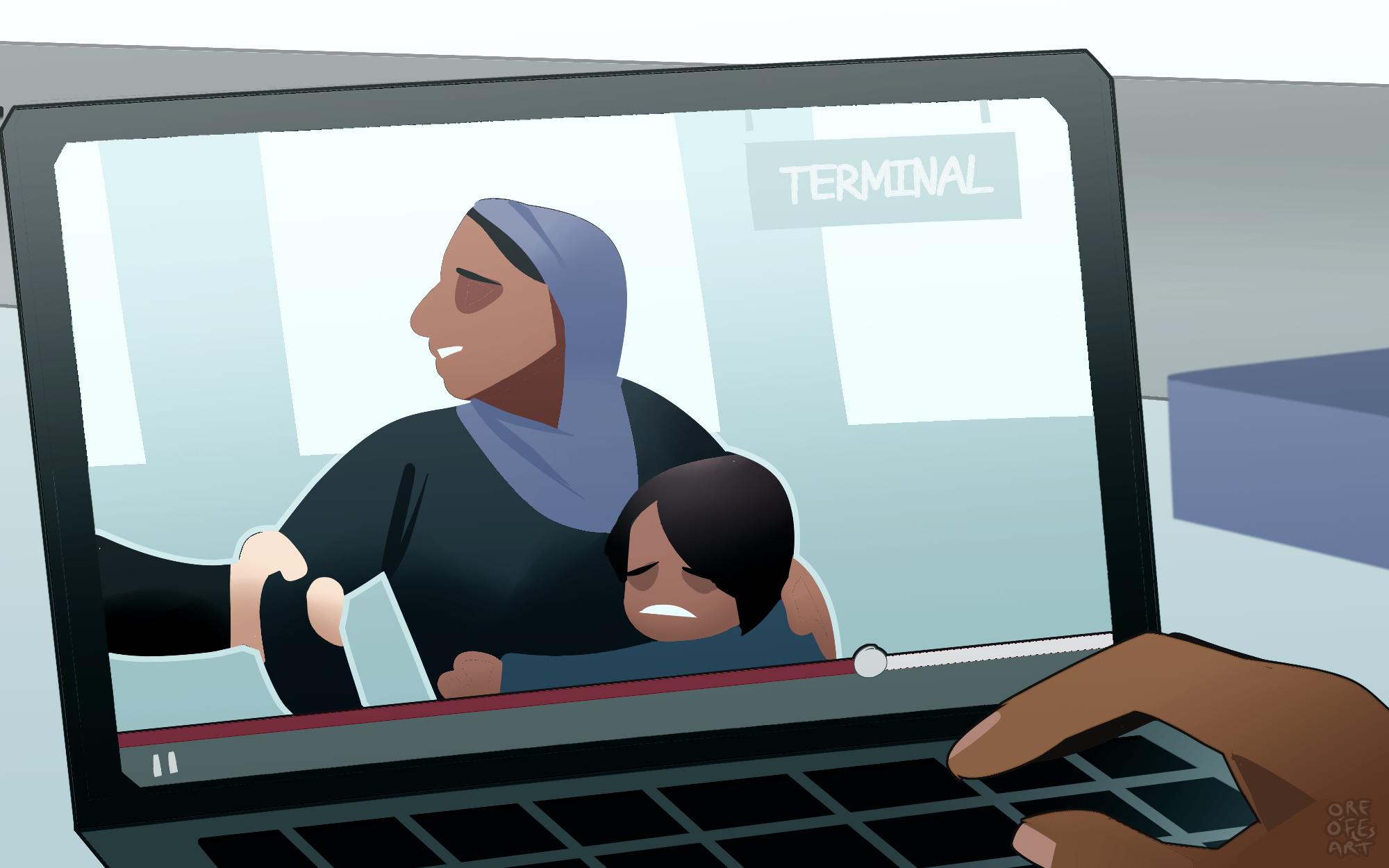

We sat around the television, isolated from one another. In our own worlds. We hoped to see something new. Perhaps a glimpse of hope is what we held onto, but day-by-day another image of destruction dug into our minds, finding its way to create a dark little home.

We stared right through our only window, watching thousands of mothers sitting in lines outside the airport, contemplating the whipping they silently endured, just so they could escape the chaos.

No papers, no clothing, no luggage – a plea for freedom is all they gripped on to. A wall stood between them and an American plane that granted safety, happiness and a new beginning in their eyes.

Drained by the insufferable images we had seen through the screen, I grabbed the remote and switched off the TV, only to find the screen is now a mirror. Dark and dull.

In this black mirror, we see our own reflections. It is clear, the horrors faced in my family’s past are now being faced by millions of others. There is no escape, there is no rest, nor good night’s sleep.

I twist and turn on my pillow, but another vivid image starts to appear. A mother throwing her new-born baby over the razor wire to strangers. Scarlet red trickling down the baby’s face whilst the mother struggled to let go of her beloved child’s leg.

Hundreds of hands waving in the air, hoping they would latch onto an American’s hand – but all I hear is their prayers and screams, “NEJAT BETE, NEJAT BETE.” One’s plea is lost amongst the echoing of hundreds of others screaming, “SAVE ME, SAVE ME.”

The countdown begins.

Three days till the last plane leaves Kabul but our hearts can’t believe this unbearable truth. Will something change? Will someone intervene?

Oh God, save my people for they still wander around in a sky filled with dust and decay but still utter your name, as they smile and pray.

We are not just restless headlines on your digital screen, we are real people and when one of us bleeds, we all bleed.

Through screens we watch as lives are lost

I wish I could turn the screen on to see and hear the playful giggles of my people again, standing tall and fearlessly. The mountains, tall and unmovable behind you, are topped with gleaming snow.

Your little feet are freezing in those ripped sandals, but you run proudly across Shor Bazar’s streets, yelling “Qaraman astem, Afghan astem”. Some of your friends have an anklet with small bells around their ankles.

They are amongst the unlucky ones, trapped and a part of a heinous crime committed by the filthy warlords, making young boys dance for them but you still have hope you’d be saved one day. Indeed, you’re all certainly Qaramans (champions).

Resilience is part of our blood now, from our great grandmothers to our future children. Even when you had nothing, you would all gather in a small circle, laughing and creating happiness out of something. “Shor” translates to movement, symbolic of the sounds and the life this street once held.

It was definitely Shor Bazar, for it was known for the immense chants, smells and tastes it was home to. The chargrilled kebab was famous, the lamb’s fat burned and filled the air in the streets with sizzling smoke. The juicy meat dangled off the sheesh, the crispy bolani made out of fresh kneaded dough and filled with earthy potatoes and leeks, fried in large deep pans.

There was always too much to explore, too much to taste, but would it ever be filled with such vibrance again?

Every corner of the Bazar looked like there was something to do. Mothers bargaining to buy second-hand clothes, sent from all over the world. The clothes market is where all the excitement was hidden. The camera man would zoom in and beneath the piles of clothes you could find a few children digging in and leaving with an item, such as a grandad’s tweed cap.

I couldn’t wait to turn on Ariana TV and see yellow, blue and green kites flying high whilst you clapped for one another and cheered during Sunday competitions.

Instead, I now wait for Sunday’s supplement on the Daily Telegraph, to see some of you wrapped in a white cloth on the back of an ambulance. Even the reporters who once strolled Kabul in their pastel coloured peran tumban, lilac, pistachio and sometimes a serene blue, the traditional clothing for men, are no longer seen on the streets.

They held their mics to the young children, giving them a voice and making them feel as grand and as famous as ever. The young boys pass their group of friends dried fruits from their pockets, walnuts, apricots and Kabul’s famous pine nuts.

They nibble on them and gossip to the reporter how they’re going to meet up in America one day and drive sports cars. How ironic, their dreams have become a necessity to escape.

Where are the fresh figs and grapes on the trees now? The leaves have become shrivelled and tainted with deep black tar. Even nature has given up, holding up a facade of strength in a land poisoned by the outside world.

It’s like our minds and hearts knew. Stealthily the ticking hands of time crept up on us. As every minute went by, it was inevitable that what we feared most had happened.

“KABUL AIRPORT ATTACK KILLS 13 US SERVICE MEMBERS, AT LEAST 90 AFGHANS” plastered the headlines.

Another blast, another remorseless theft of innocent lives. The explosion preyed on them ripping through the desperate crowds stealing the last remaining thoughts of a new life each victim had.

The air smells destructive, filled with the odour of burnt corpses laced with the noxious stench of worldwide betrayal.

I can smell it through the phone, I feel as though I am there, but I am not. I lie in my bed, under a warm roof, cold inside, trying to feel their pain through a screen. I’m trying again. Is sharing, tweeting and commenting enough?

You would think there would only be a few remaining at Kabul airport now. But the crowds this time are filled with even more hands, waving recklessly in the air, stained with fresh blood, sirens rattling the air. Flashes of red and blue have become the only colours I see of my land.

There is no light. The snow would once fall upon the fig and grape trees, as bright as day, until they stole the light of land from us, leading a fleeting moment astray.

How can others understand the pain of losing your country?

My thumb senselessly scrolls through social media posts, one captioned “YOUNG GIRL, SOLD TO AN OLD MAN FOR $2,200 IN AFGHANISTAN.”

Hunger has taken over now. There is no childhood left in Afghanistan. We read, hear and are told by our communities of girls raped by men decades their senior. Their little feet dig into the dirt as they’re being dragged away to a life of servitude. Sold by fathers who neglect their duty of protection. They cup their little hands in prayer, pleading for relief, perhaps in the form of escape or even death.

It kills me to think that a child nearly half my size whose only worries should be homework and playing games, is forced to sleep at night next to an old man.

A priceless gift. A priceless child is sold. For just a few thousand that will soon run out. She’ll have to bear a child while she remains one herself. She’ll have to shape another human before she can shape her future.

I wonder how her mother can function with her broken heart when I, a stranger so far away from her reality, can barely function with mine.

If I speak of this pain to another, they’ll nod and simply say, “I’m here for you”.

They could never understand the pain of having to live life knowing you lost your country, knowing your country had lost its last remnants of humanity.

We move through life with a lump in our throats, with the grief of spatiality, distant friends and strangers heavy on our hearts, with sadness in our smiles and a sense of profound loss that no one could ever understand. I’ve become glued to the screen again.

I think of all the Afghans who have lost more than I have. The homes they thought they would die in, the people they thought they would watch grow old, the livelihoods they spent a lifetime building.

I think of the Afghans who have nowhere to escape to, who go into a new year with old pain, with empty stomachs and worries too heavy to hold.

I think of all the Afghans who have paid the ultimate cost of war, the ones who died in an ideological battlefield, the ones who died inside their universities or their workplaces, the ones who died whilst running an errand hoping to be home soon and the ones who didn’t get their last goodbye.

The ones who didn’t even get a full day of life on earth, the ones who fell off airborne planes and the ones who lived but felt something die inside when their country fell.

I’m trying again. This time maybe I can make the newly arrived refugees in the hotels smile. I volunteer at the drop-off locations, organising books, clothes and toys. Am I getting any closer?

It’s been a long week sorting, giving, travelling, grieving. I watch Parwana and her two brothers from the car window, waving goodbye to me as they hold up donated pens and notebooks they’ve been gifted.

I hope to hear the sounds of joy and smells of excitement back in Afghanistan again.

Until that day arrives, I’ll continue to watch, and to try.

All images by Oreofe Morakinyo.

Read more: