Writer and artist Nasrin Parvaz spent eight years in the same Iranian prison where Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe is now being held and has used the experience as inspiration for her novel. She says there are echos of Nazanin’s story in prisons across Iran.

“It’s not even a mixture of sweat, pain, blood, burning skin or…The smell of torture is different from all these. One would only find it in prison and I have no name for it. Perhaps its very vocabulary has died under torture.” (From The Secret Letters From X to A by Nasrin Parvaz.)

“It’s not even a mixture of sweat, pain, blood, burning skin or…The smell of torture is different from all these. One would only find it in prison and I have no name for it. Perhaps its very vocabulary has died under torture.” (From The Secret Letters From X to A by Nasrin Parvaz.)

The smell of torture is a smell that writer, artist and human rights activist Nasrin Parvaz knows well, as she herself was imprisoned for her political activism by Iran’s Islamic regime in 1982.

Writer Nasrin Parvaz

Parvaz, who turned 60 last year, was born in Tehran, but moved to England in 1978 at the age of 20 to study. She returned to Iran during the 1979 Islamic Revolution and became a civil rights activist and member of a socialist party.

After the revolution, which overthrew the authoritarian monarchy of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and installed Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini as the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic, there was so much hope, she tells me over coffee in London where she now lives:

We thought we could have democracy and freedom and that men and women would have the same rights.”

But under the clerics’ strict rule, thousands of everyday acts (such as listening to pop music or drinking alcohol) became forbidden and those who didn’t think along the party line were punished.

“So many of my generation were imprisoned, tortured and killed by the Islamic regime, but the younger generation has no idea of what happened in the 80s,” says Parvaz.

“They say that we put Khomeini in power, so they are angry with us. They learned the regime’s version of history through TV and school.

“They don’t know our story because we never had a voice – even in exile.”

Like so many young activists from her generation, Parvaz, at the age of 23, was arrested by the regime’s secret police after having been betrayed by a comrade. She was tortured and sentenced to death, but her death sentence was commuted to 10 years in prison.

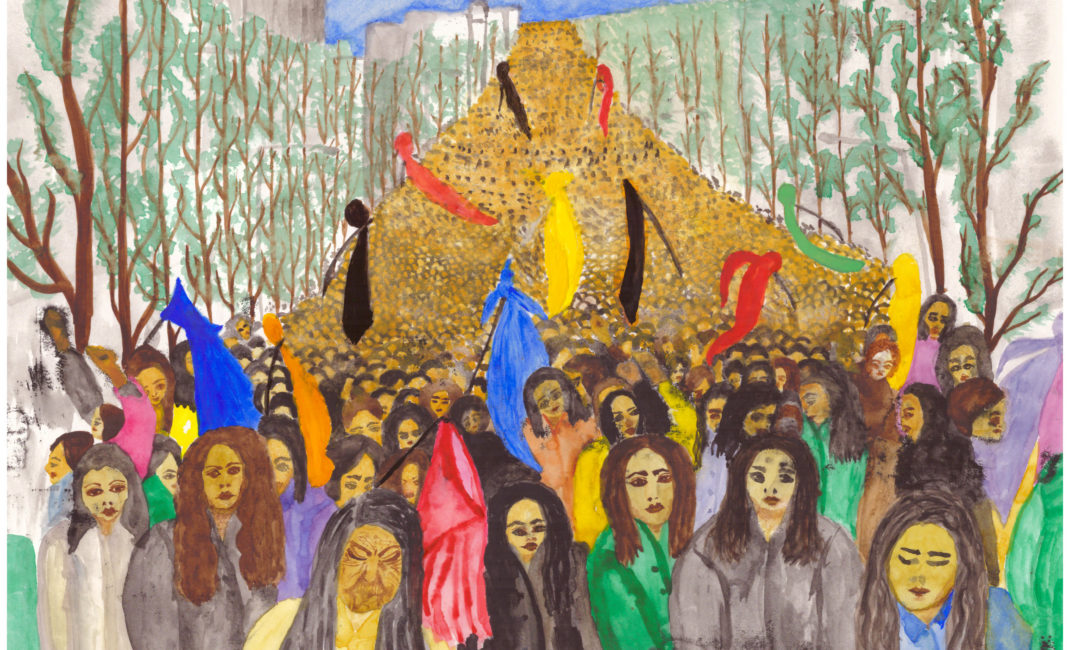

A demonstration by women on 8 March 1979 when Khomeini said that women had to cover their hair – by Nasrin Parvaz

She was released after eight years in 1990, and resumed her political activities. Once again, she found herself being followed by Islamic guards, so fled to England, where she claimed asylum in 1993. She was granted refugee status a year later and has since been living in London, where she continues to draw attention to injustice and human rights violations in the country of her birth and elsewhere.

Read more: Postcards from Persia: Twelve nights in Iran

The plight of British-Iranian charity worker Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who since 2016 has been languishing in Tehran’s Evin prison after being accused of spying, may have briefly turned UK attention to the treatment of prisoners in Iranian jails.

But right across Iran, prisons are filled with thousands of journalists, writers, workers, activists and lawyers arrested for their political or religious beliefs or on various trumped-up charges. And many are tortured and killed.

Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s physical and mental health have suffered while she has been in Evin prison. She recently went on hunger strike in protest against being denied medical care.

“There are echoes of [Nazanin’s] story everywhere,” says Parvaz. “So many people are arrested for flimsy reasons – especially since the uprising against the regime.”

With her first novel in English, The Secret Letters From X to A, Parvaz herself echoes the plight of many political prisoners. Published by Victorina Press, a small independent publisher for multicultural authors, the novel takes us inside Iranian prisons – a parallel world with its own language.

“The language here is not spoken, though it still has the quality of sound. It reminds me of a heartbeat, which is sometimes louder and faster, and it means that the guards are no longer managing to separate us,” Parvaz’s protagonist writes about the morse code, which inmates have learned to communicate between cells.

In the novel, the protagonist, Xavar, writes lover letters to her husband, Azad, in a series of secret notebooks. The letters of this young, pregnant political activist, imprisoned in 1984, draw us into the claustrophobic, cruel and arbitrary life in the Joint Committee Interrogation Centre, one of Tehran’s most notorious prisons at the time (Parvaz herself spent six months here before being transferred to Evin).

The notebooks describe the daily interrogations, the routine humiliation, the sadism of the guards, the torture, the rape (documented by human rights organisations as being used to intimidate, break down and punish prisoners) and the constant fear of execution. But they also describe the solidarity between female inmates, their courage, their passionate political discussions, their creativity and resilience and the little gestures of kindness, which allow them to survive.

In her letters, Xavar, for example, describes 13-year-old Mitra, who had made a toy mouse out of a washing sponge and was playing with two children “until one of the guards opened the door on hearing the children laughing and confiscated it. Mitra reminds me of those fish, born in the sea but captured and left in a tank that hit the wall every time they try to swim as far as they used to. Mitra’s situation is like theirs and I’m worried that every time she hits the glass, something inside her breaks.”

Child and mother (in prison), by Nasrin Parvaz

And later in the notebooks, Xavar depicts the unbearable moment when Mahvash, who was like a mother to her in prison, was called by the guards for execution:

“She kissed me and wished that I would ‘stay alive’ as she went. ‘Stay alive’ are the last words uttered by those who go to be executed to us who are still living. They are the same words, spoken in different accents and with varying degrees of fear, hesitation, anxiety, confusion, or even happiness that I have heard so many times here.”

Xavar’s hidden notebooks are discovered almost 20 years later by Faraz, a young history teacher, who has accepted a summer job converting the Joint Committee Interrogation Centre into Ebrat, a museum showcasing repression under the Shah. Reading Xavar’s diaries while repainting and re-plastering the cells filled with graffiti and messages, Faraz understands too late that by doing so, he will erase all evidence of the human rights abuses committed there by the Islamic regime.

Parvaz says: “Ebrat means ‘warning’. Children are taken there on school trips.

I wanted to write this book when I learned that they were going to turn the Interrogation Centre into a museum showing only conditions under the Shah, but nothing about our time. The Islamic Republic of Iran wanted to whitewash what had happened there for 20 years under the current regime – the thousands of people tortured and executed – and pretend it never happened.

“The Islamic regime is a master of concealing and deception. When the UN human rights inspectors came to visit Evin prison in 1990, they built a new wall across our corridor to conceal us. We never met the inspectors. While president [Hassan] Rouhani [elected in 2013] publicly promised reforms, behind closed doors, there are still too many prisoners dying in detention.

“Prisons are still full of men and women fighting for civil rights. Questioning how and why the regime operates is still dangerous.”

Read more: The Orange Trees of Baghdad In Search of My Lost Family

In Parvaz’s novel, the distressing scenes hit the reader so hard because they feel real.

“The diaries are based on the true stories of other women I was in prison with, but they are not mine,” Parvaz explains.

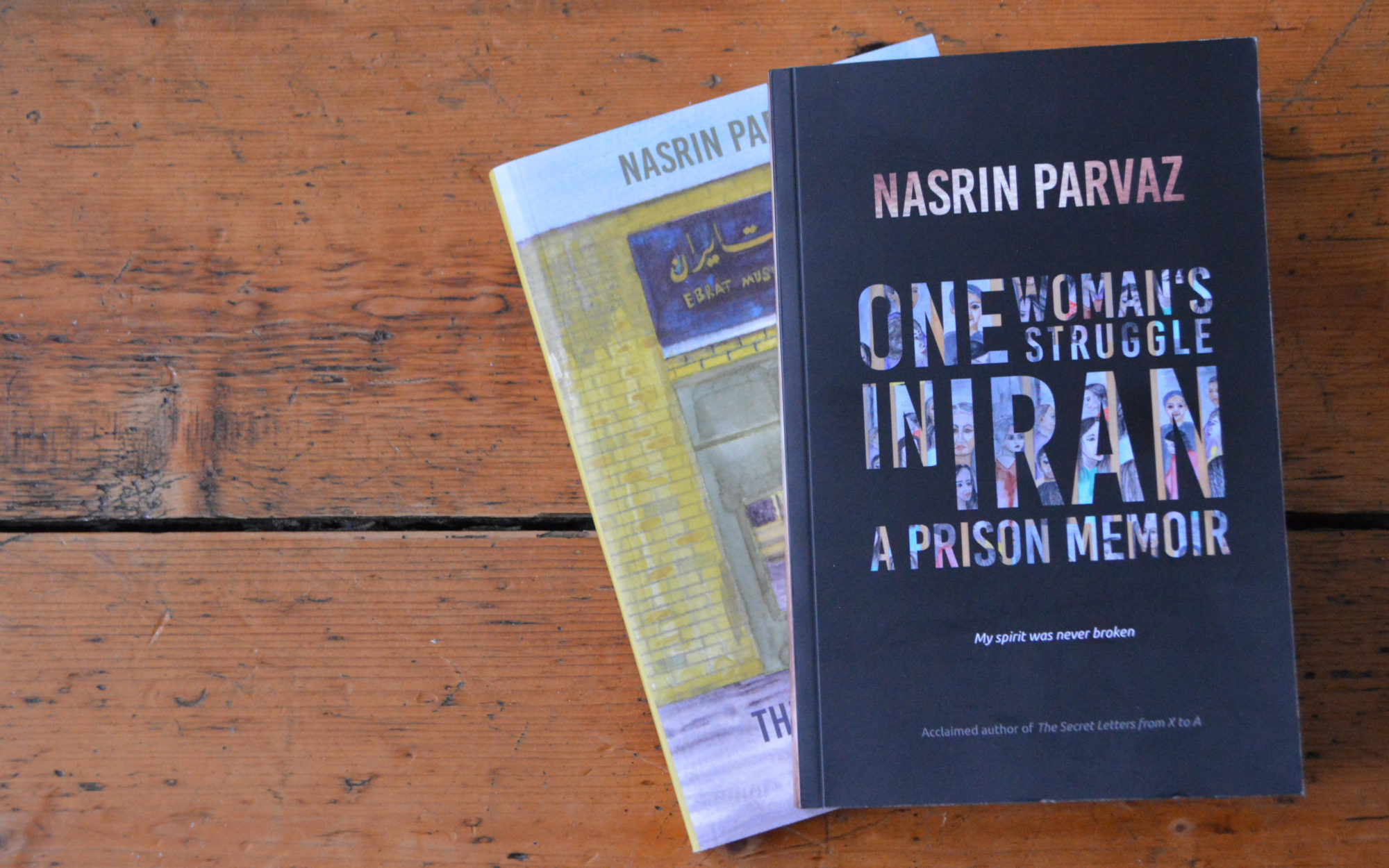

She did however publish her own prison memoir in Farsi in 2002, which has just been published in English by Victorina Press as One Woman’s Struggle in Iran: A Prison Memoir.

She did however publish her own prison memoir in Farsi in 2002, which has just been published in English by Victorina Press as One Woman’s Struggle in Iran: A Prison Memoir.

“In my memoir, I wrote about what I saw and what happened to me in prison, my journey there and my friendship with other prisoners,” she says. “In my novel, I was free to enter into a new journey, experiment with ideas and express feelings that were not necessary mine or relevant to the memoir.”

In a work of fiction, she adds, she could also address the corruption and hypocrisy of a regime that keeps “the poor in order but [is] not policing itself”, and show how little has changed decades later.

Safe in exile in London, Parvaz continued to be haunted by her past. Suffering from nightmares and flashbacks, she sought help from the UK-based human rights organisation Freedom From Torture, where she received psychotherapy for many years.

This led her to study for a degree in psychology, then a Postgraduate Diploma in applied systemic theory and later work as a family therapist. It is also there that she found her voice as a writer.

Through the organisation’s creative writing programme Write to Life, she learned to revisit her past and put into words what had no words.

“In prison, I saw so many terrible things, which I couldn’t understand or even think about, like rape and suicide. There are things happening in prison, which the outside world has no words for.”

The act of writing, she says, helped her understand the impact prison had on her and “pour that pain and suffering into the sea”.

But her novel is more than cathartic, it also tells the story of her generation, as Parvaz puts it: “The Iranian men and women who became politicised during the revolution and fought for their rights, for solidarity and against the oppression of women.

“I wanted to write this book to make people stand up against torture and execution. Without the fear of execution, people will stand for their rights.”

Nasrin Parvaz is now working on a new novel and painting.

The Secret Letters From X to A and One Woman’s Struggle in Iran: A Prison Memoir are both published by Victorina Press.

- For stories like this direct to your inbox, subscribe here. Or follow us on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.