Since one of the fastest growing migrations in recent history, the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh have been living in a climate of uncertainty and mistrust. Now, confronted by a global pandemic and the prospect of being banished to an island for quarantine, will the Covid crisis strip the last remaining rights of the Rohingya people?

August marked the three-year anniversary of what quickly became one of the fastest growing refugee movements in recent history. In August 2017, nearly 700,000 Rohingya found refuge in Bangladesh, fleeing ethnic violence in the neighbouring Rakhine state of Myanmar. Since then, more than 1 million Myanmar Rohingya have been living in refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, a city in south-east Bangladesh. The camps not only form the largest refugee settlement in the world, but also the most densely populated.

Since the first Covid-19 case was identified in the camps in early March 2020, many feared the worst. An early report from the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health projected that even in conservative estimates, after the initial infections in the camp, a large-scale outbreak was highly likely.

Although the number of infections reported remains low, with 79 cases detected and six deaths, many human rights organisations including Amnesty International have warned that measures adopted during the early days of the pandemic are insufficient, overlook some of the most vulnerable members of this community and in some cases violate the rights of the Rohingya people. Some of these measures have reignited deep-seated fears among those living in the camps, causing rumours to spread across the communities, further challenging local Covid-19 prevention work.

These widespread fears are not new and are deeply rooted within the Rohingya community in Bangladesh. To understand this fully one would need to follow their three-year journey, since their traumatic arrival in Bangladesh in 2017.

A breach of trust

“The Bangladeshi people in Cox’s Bazar where the first ones to intervene,” one Rohingya elder remembers back to 2017. “They brought us food, clothing… We are very grateful to the Bangladeshi people.”

But not long after, things began to change. An area where around 200,000 Bangladeshi used to live, now had to accommodate over 1 million Rohingya, and this had a considerable impact on the local communities. Jafaralam, a 40-year old Bangladeshi farmer from Ukhia Upazila in Cox’s Bazar, explains that some took advantage of the situation by employing Rohingya for work outside the camps and, banking on their vulnerability and willingness to work for less, decreased all salaries from 1,000 Taka [£9 GBP] a day to 300 Taka [£3 GBP]. This together with a series of forced land expropriations to extend the refugee camps, fuelled tensions between the Rohingya and the local communities.

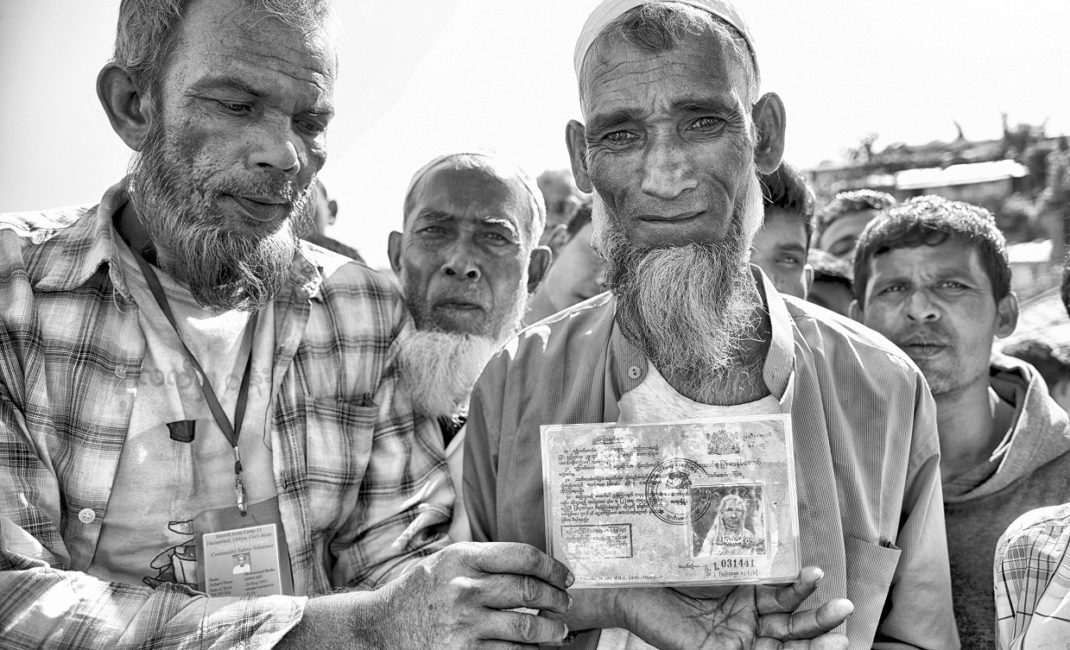

1. A group of refugees in the Jamtoli refugee camp showing their Myanmar citizenship cards. Although some of the elderly refugees have citizenship ID, the government of Myanmar has long considered the Rohingya as foreign citizens, greatly challenging any repatriation negotiations – by Francesc Galban

In February 2018, the government of Bangladesh started plans to relocate the Rohingya living in Cox’s Bazar, by building a refugee camp on Bhashan Char, an uninhabited island in the Bay of Bengal. Although initially planned as a way to free up space in the camps and ease tensions, Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has said it could at some point accommodate as many as 1 million Rohingya. The island is located in an area prone to cyclones and unpredictable floods and is considered by NGOs and human rights organisations as unsafe and not fit for purpose. This decision was immediately met with opposition from the Rohingya community who felt the right to choose had been once again taken away from them.

In November 2018, amid the pressures of a general election, the Bangladeshi government decided to pilot a programme of voluntary Rohingya repatriations. We met Mohammed Hasson some time in December that year. He was in hiding and had been moving between friends and relatives in different camps since November of that same year, when his name appeared on a government list for repatriation.

Like many other Rohingya, he arrived in Bangladesh a year earlier, between August and September 2017. In Myanmar, Mohammed was captured by the army alongside his two older brothers. He was 15 years old at the time. He was tortured for hours alongside other Rohingya people in a military compound. They were finally grouped and shot at repeatedly. He was left for dead in a mass grave beside his two dead brothers.

Mohammed Hasson showing his wounds in a friend’s makeshift hut in the Kutupalong Refugee Camp – by Francesc Galban

“When I woke up, I kept my eyes shut and waited for the soldiers to leave, and then I ran towards the forest.” After five days looking for a way into Bangladesh, Mohammed was found by a group of Rohingya escaping a massacre in a nearby village. They cleaned his wounds and crossed into Bangladesh, where he underwent emergency surgery.

Every day I think that I would have been better off dying on that day next to my two brothers”.

Like Mohammed, many others on that list had no intention to go back to Myanmar, and resisted repatriation. Between November and December 2018, the Bangladeshi army entered the camps, and riots broke out. Many elders that had made this very same journey before, first in the 70s and then again in the 90s, told us that, they were not going to trust “the empty promises” of the Myanmar government, not again. They would rather take their own lives than to go back to Myanmar.

Read more: GALLERY – The human and environmental toll of mass Rohingya migration

There is no question now that repatriations and relocations were a failed attempt to ease tensions in the area. If anything, it was a blow to the trust and hopes of many Rohingya that at the time considered Bangladesh a safe haven.

Amid this climate of uncertainty and mistrust, the Rohingya are now confronted by a global pandemic that has already taken over 700,000 lives and infected nearly 20 million people worldwide. Many fear that the Covid-19 crisis will be used as an opportunity to take rights away from the Rohingya and limit their freedom. Others worry that the lockdown will severely affect the already-weakened lines of support.

A fragile balance

Since the beginning of the lockdown, and as a measure to reduce the risk of infections, NGOs decreased staff presence in the camps by 80%. This measure alongside the government’s decision to restrict access to some NGOs applying for new projects, has left the camps drastically underserved.

For Foyazl Islam, a resident of the Kutupalong-Balukhaly camp, the issue is clear: without the NGOs in the camps, life for the Rohingya has become a lot harder. “Our shelters are very damaged because of the monsoons, and due to the lockdown, we didn’t get any materials to repair them.” He says that although they have been asked to stay at home as much as possible, he finds it very difficult to stay in. “[Because of the damage] when it rains the water leaks into the house… It is very hard to sleep.”

Foyazl Islam in the Balukhali Refugee Camp – by Francesc Galban

But the difficulties extend far and beyond housing conditions. The fragile and unforgiving economy of the camps, determines now, more than ever before, livelihoods. Foyazl has not been able to work since the lockdown started. The little money that he earned helped him supplement the food rations his family receives from the World Food Programme (WFP) and buy additional supplies. “Now the rations and food distributions have been reduced. It is not enough for us to survive, and supplies in the markets and shops are difficult to get and more expensive.”

A resident of the Jamtoli camp confirms that a shortage of basic products and the ever-growing demand has made market prices increase dramatically. “Before the lockdown, 1kg of fish was around 100 Taka [£0.90 GBP] but now it is more than 200 Taka [£1.80 GBP]. Also, people have lost their income as during lockdown they cannot work.”

In a place where malnutrition is an endemic issue, the news of shortage of supplies is alarming. Many Rohingya like Foyazl worry about their prospects if the current situation continues as it is, particularly regarding the access to health facilities. “I am not only worried for me but for everyone. Health facilities in the camps are not enough for everyone; if there were better facilities, then we would have a better chance.”

Read more: The price of silence in Myanmar: Who is to blame for the plight of the Rohingya?

This concern is shared by Noor Hossain, a resident of the Kutupalong-Balukhaly camp. Since the beginning of the Covid-19 response, Noor has been recording complaints from community members.

The camps are not well resourced. If you reduce by 80% the NGO presence you can imagine the consequences.”

Many Rohingya have come forward to complain about the healthcare they receive, from strenuous waiting times to the lack of proper examinations. “I have heard of many, many cases where no physical examination was carried out. The patient is asked from a distance a few questions, and based on the answers, drugs are prescribed.”

Noor tells us that a relative of his was recently denied access to the Hope Foundation Hospital. Noor shares a photograph showing a woman who is lying beneath blankets on a stretcher on the bare floor, next to the main gate of the clinic. “The staff in the clinics are very scared of Covid,” he explains. “She arrived at the health centre with fever and was refused entry. After two hours waiting, she was sent to the MSF Hospital, where she died. We were told that she had no Covid”.

A great proportion of the Rohingya population living in the camps suffer from underlying health conditions. Due to the Covid-19 restrictions, healthcare support has been drastically reduced. In the image a mother takes care of her disabled daughter in their makeshift hut in the Kutupalong Refugee Camp – by Francesc Galban

Distribution of supplies to tackle the pandemic have also been affected by the lockdown. Ayas, a volunteer team leader with the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) confirms that at the moment it is difficult to ensure basic hygiene and protection within the camps.

“The provision of soap is not enough, but the real problem is clean water. People have to carry water from the well, at the bottom of the hill, to the house at the top”. In addition to this, wells are not always functioning, and water shortages are common. “Although there is a water distribution point, the queues are long, and after waiting until the evening, people can only get 3 or 4 pots of water. That is simply not enough water for drinking and washing your hands.” Aya also tells us that the DRC together with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) have been distributing masks among the community, but supplies are scarce. “We have been distributing two cloth face masks per household, but that is not enough for all the family members.” Face masks are available for sale in the markets around the camps, but they cost anything between 20 to 50 Taka [£0.18-0.45 GBP], too much for many Rohingya that have to make the choice between staying safe from the virus or being able to buy supplies for subsistence.

Farjina with her two sons, in their makeshift hut in the Balukhali Refugee Camp – by Francesc Galban

For Farjina, a 25-year-old mother of two, the concerns are altogether different. As NGO-run schools and Madrassas (Muslim schools) have been closed since the beginning of the lockdown, in order to avoid the spread of the disease and ensure social distancing, children in the camps remain at home unable to access education. “As Madrassas and schools have been closed, my children are having no education. If this [lockdown] continues for longer I fear for the future of our children.”

A measured response?

Sirazul Islam, now 18, was born in the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp. In 2008, as part of The Gateway Protection Programme, a resettlement programme for refugees, he was granted asylum in the UK. Acting as youth advocate for the Bradford-based human rights group The British Rohingya Community, he is concerned with some of the measures adopted in the camps as part of the Covid-19 response. Particularly concerning is the announcement that the Bangladeshi Government would use the Bhashan Char island as one of the quarantine facilities and relocate some Rohingya there. He says: “The fears I had actually became true the moment they [the Bangladeshi Government] transported Rohingya into Bhashan Char island without their consent.”

A group of children in front of a store in the Kutupalong Refugee Camp. According to UNICEF, 58% of all refugees are children, with 60 babies being borne every day in the camps, adding to the demographic pressure in the already congested camps – by Francesc Galban

Many Rohingya refugees attempt the dangerous journey from Bangladesh to Malaysia in search of a better life. Since May 2020, hundreds of Rohingya, intercepted on the southernmost coast of Bangladesh on their way to Malaysia have been taken to quarantine in Bhashan Char. Sirazul believes that this violates the rights of the Rohingya as they are taken to the island against their will and without informing their families. Above all, he says, the Rohingya feel trapped and scared.

They are all genocide survivors. I cannot ask you to walk in their shoes, but it makes you wonder, when are they going to be treated as human beings? They have been through so much that the pandemic is the least of their concerns. They would rather suffer from the virus than be separated from their family again. That’s the sentiment.”

Mohammed Sultan has not seen his daughter Asma since early April. She left the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp to take a boat to travel illegally into Malaysia. Smugglers charge around 40,000 Taka [£360 GBP] per person – a lifetime of savings for most. After one month of journeying adrift in a leaky boat, Asma, alongside other refugees, were intercepted by Bangladeshi authorities, arrested and taken to Bhashan Char. “My daughter was taken to the island in May. We miss her so much, and we worry about her”.

Read more: The defiant Rohingya of Bradford

Communication is difficult and Mohammed has not had any news from Asma since mid-June. “Currently I have no access to communication with my daughter, I have only talked to her three times on the phone since May.” When asked about the living conditions on the island, Mohammed tells us that Asma is not allowed to move freely from one building to another and remains all the time in one room, with no NGOs to support her there. “She was crying a lot when I talked to her, no one is allowed to leave the island; she feels like a prisoner. I am eager to get my daughter back at any cost”.

The spread of rumours

Like Mohammed Sultan, many other Rohingya people have been unable to communicate with their relatives for some time. Since September 2019, the Bangladeshi government has enforced a telecommunication ban on all the Rohingya people living in the camps by blocking internet, and not allowing them to buy or own SIM cards under the premise of maintaining security. With little to no reception in the camps, and the internet being blocked, it is nearly impossible to communicate.

[Editor’s note: at the time of publication, the internet ban had been lifted]

Ro Sawyeddollah, an 18-year-old resident of the Jamtoli camp, confirms that since the start of lockdown many Rohingya have lost contact with their family and friends living in other camps: “I have not been able to contact my family since the lockdown started. They live in the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp. Before, there was one army checkpoint in Ukhia Upazila, now we cannot move from one camp to another as there are many checkpoints between camps, and with the internet ban it is very difficult to communicate”.

One refugee says he has been fortunate, as since the beginning of lockdown, he has managed to contact his relatives living in another camp by using a Myanmar 2G SIM card, “but there is only one point in the camp with access, on top of a high hill. It is hard to get to.”

Many others like Ro Sawyeddollah do not know if their relatives living in other camps are safe, resulting in a great deal of distress. But this is not the only problem caused by banning all communications in the camp. Kasim and Faruque both concur: “There is a lot of misinformation and rumours in the camp about this [Covid-19]”. The rumours are many, but they have a common denominator:

People feel that anyone that is tested or goes to the health facility will be killed or taken to an island by the government”.

Faruque adds: “The main issue is the lack of trust in the government and the organisations”.

Sewage water running through households in the Balukhali Refugee Camp. Maintaining hygiene has become one of the more challenging issues as part of the Covid-19 prevention plans – by Francesc Galban

Faruque and Kasim arrived in the camp in 1991 and 2017 respectively and have been living in the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp alongside their relatives ever since. In March this year, amid the confusion created by the lockdown measures, they co-founded Omar’s Film School, a Rohingya-run and led community engagement initiative aiming to “create awareness among the Rohingya on what the virus [Covid-19] is and what to do to stay safe” Faruque explains: “Most of us are uneducated and have very little information particularly now with the internet ban.” The members of Omar’s Film School go door-to-door, sharing information leaflets and educational videos with community members. Faruque says: “We mostly target elders as they are very vulnerable and the youths, so they can teach other members of their families. Members engage with NGOs still active in the camp to collate information, and check updates from The World Health Organisation, but very few have access to network and connectivity within the camps.”

When asked about the internet ban, Faruque is quick to respond: “A very bad decision; when you lack information, rumours spread faster.”

Putting trust in the future

For Mohammad Mainul Islam, professor in the Department of Population Science in the University of Dhaka, although the intervention to date has been faced by many challenges, “We shouldn’t panic; but we need to intervene urgently.” It is clear that the lack of information, the spread of rumours, and fear, are among the main challenges, and for that he says: “We need to build confidence among the Rohingya. The fear of isolation and separation from their relatives is persistent, but unless we can build trust among the Rohingya, it will be very difficult to achieve a successful intervention”. The lack of robust data on infected Rohingya as a result of a low rate of voluntary testing within the camps is greatly challenging the prevention work. Prof Islam says:

Data is very important; we need more reliable data. How can we make a meaningful analysis without testing? Ultimately, we really don’t know what is happening in the camps.”

But these are not the only challenges. The intervention in the camps is currently suffering from a systematic lack of adequate support, as the preventive measures are not reaching the majority of the Rohingya people. Prof Islam continues: “Until the end of July, only 14,000 of the existing 187,000 households had been provided with adequate hand washing and hygiene kits, and only 32,000 households were distributed soap regularly… It is clear that the prevention measures are not sufficient.” When asked about a potential ease of the lockdown measures in the camps the professor is clear: “At the moment we can only work on prevention. Undoubtedly the only long-term solution involves vaccination but when will the vaccine become available to rural, poverty-stricken populations? Who will provide the funds for 1.1 million vaccines for the Rohingya people? We don’t know.”

Read more: