As Thailand faces a crisis of democracy, controversial laws are targeting a new wave of protesters. But who are they? What drives them? And how can they hope to challenge a regime that seems hell-bent on stopping them?

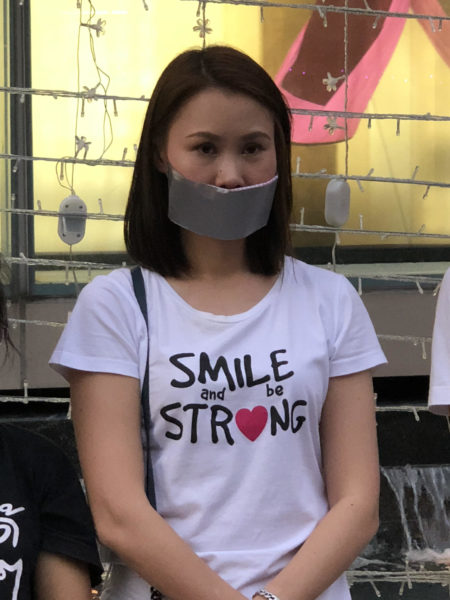

A woman stands surrounded by a scrum of photographers, her arms crossed in front of her chest in a symbol of peace. Silver tape covers her mouth to signify a silent protest for democracy.

This is Nuttaa Mahattana, or Bow to her friends and supporters.

Ten years ago she was working as a marketing manager for the British Council before becoming a teacher, a corporate trainer and sometime television presenter on the popular Cozy Living show.

Now, aged 39, Bow is one of the leaders of a growing resistance movement against the military dictatorship which controls Thailand.

Since seizing power in a military coup in 2014, General Prayuth Chan-Ocha has cracked down on all dissent. Elections have been promised and regularly deferred.

General Prayuth represents the Yellow Shirts in an increasingly polarised Thai society where class and political divisions have come to be represented by the colours the supporters wear.

When supporters of deposed Premier, Thaksin Shinawatra, drawn from the rural poor and radical students, took to wearing red T-shirts at public gatherings, the reaction came in the form of The Yellow Shirts, a loose grouping of royalists, ultra-nationalists and the urban middle class.

The leaders of the Red Shirt movement have now been exiled, imprisoned or cowed into silence and the last two democratically elected prime ministers, Thaksin Shinawatra and his sister Yingluck, are now in exile.

Nuttaa Mahattana(or Bow). Image by Papinwat Pateepnampapon

But from the wreckage of this movement new activists have emerged, including Bow.

Although she had always taken an interest in politics it was never in an active way, until her celebrity led to her being approached to support various causes and campaigns.

One such campaign concerned a young student, called Pai, who was thrown in jail for violating the Lese Majeste law, which strictly forbids insult of the monarchy.

His crime? Sharing a post on Facebook – a short biography of the new king from the BBC website.

The Lese Majeste law has been in place since 1908, but was seldom used before Prayuth seized power three years ago.

Since then, it has become one of the main tools used by the junta to suppress dissent, being used to bring more than 100 prosecutions for sentences of up to 35 years.

Most of these cases have been brought against political activists.

The law (Article 112 of Thailand’s criminal code) says that anyone who “defames, insults or threatens the king, the queen, the heir-apparent or the regent” can be sentenced to between three and 15 years in prison. And the sentence is per offence, so the author of a series of Facebook posts, for example, could find themselves jailed for 15 years for each one.

Because of the alacrity with which the regime pursue activists who they deem to have transgressed Article 112, it is difficult to get anyone to talk on the record about Lese Majeste.

The army monitors key activists 24-hours-a-day, seizing any opportunity to remove a political opponent from the scene.

To exert control, the junta, on taking power, enacted the Assembly Law, prohibiting political gatherings of more than five people.

Although this law is rarely pursued in court, it is used to break up or prevent demonstrations and has led to the arrests of many protesters, including 50-year-old Anurak Jeantawanich, who gave up his job as college lecturer seven years ago to become a full-time activist.

Anurak had gone to a Red Shirt protest out of curiosity and spent several days there, talking and listening to people.

Anurak Jeantawanich is pictured at a protest in Rachaprasong.

He witnessed the violent crackdown, where live ammo was used on the protesters, and his fate as an activist was sealed.

None of the deaths was reported in the Thai media.

He said: “When I saw what really happened it hurt me. So from seven years ago until now I never stopped fighting for democracy.”

He founded Red Path project, organising cycling trips around Thailand and neighbouring countries to raise money and awareness about democracy, human rights and political prisoners.

This project ended with the military coup in 2014, but Anurak continues to visit political prisoners and their families to let them know that they are not forgotten.

When it comes to the Assembly Law, Anurak exercises caution: “We can’t gather in groups of more than five? No problem, we’ll go in threes and fours. We can’t wear a red shirt? No problem, we’ll wear orange and then no one can say if we are red or yellow.”

Other activists, however, simply do their best to ignore the law.

Rangsiman Rome is from the student activist movement, which has a long tradition in Thailand.

Now 25, he left the beautiful island of Phuket 10 years ago to study in Bangkok.

With a handful of friends Rome set up the Democracy Restoration Group.

Since the coup in 2014 Rome has been arrested three times and kept in military jails for a total of 25 days without being formally charged.

Rangisman Rome. Image by Israchai Jongpattranitchapan

In his campaigning, Rome tries to connect the myriad small opposition groups around a common aim “to kick the military out of democracy.”

Between the 1932 Siamese Revolution and today there have been 19 coups in Thailand.

The country is trapped in an endless cycle of elections followed by military coup.

This has been characterised in this century by the clashes between the Red Shirts and the Yellow shirts.

The Red Shirts tend to represent the rural poor, the majority in Thailand, and they have tended to win recent elections.

The Yellows represent the urban elites and the establishment who usually assume power after a military coup.

So how can the current crop of activists break this destructive cycle?

Nuttaa Mahattana (or Bow), by Israchai Jongpattranitchapan

Bow feels that the 2014 coup could be the last: “People have learned a lot of lessons in the last four years.”

Rome believes it’s not enough simply to kick out the military government, instead saying they must be prosecuted for the coup.

Only by punishing them for their actions will a message be sent to the military – and the people also – that the old ways have ended.

He adds: “If the military are considering a coup in the future, they will know there will be consequences.”

This has not happened previously. Each election just provides a reset and the cycle begins again.

Despite the challenges they face, Thailand’s activists retain a strong belief that they will prevail. They share a sense of optimism for their country’s future, but agree that it will be a long road.

Rome says: “I think time is with me. I’m 25 and when I look at my peers I have hope.

“No one in my generation supported the coup.”

Despite this optimism, opposition to the military regime in Thailand is fraught with danger.

Since they were interviewed for this article, all three activists, Bow, Anurak and Rome, have been arrested and released, as both protest and military suppression in Thailand intensifies.

Rome is arrested during a protest in Thailand. Image by Thitinun Sampiphat.

At a peaceful protest Bow, Rome and Anurak were among 39 activists charged with violating the Assembly Law and with sedition.

However they remain defiant and unbowed.

“A fire has been lit!” Bow says taking to the streets for a silent protest, with a tape across her mouth.

It is not difficult to share the optimism of Anurak, Rome and Bow when you see their determination and bravery.

They demonstrate that suppression of dissent cannot kill the green shoots of opposition.

Main image by Thitinun Sampiphate

- For stories like this direct to your inbox subscribe here.