Part 1: Images of India

Annual General Meetings are rarely inspiring. But there can be exceptions. A year or so ago I walked into a hall in east London to join the AGM of Action Village India, a small charity supporting non-violent movements for change in the sub-continent, and was confronted by a line of huge photographs printed on boards and propped up along the walls. It was a stirring sight.

These weren’t enlarged ‘snaps’. They were a series of breathtakingly evocative pictures that immediately enthralled with a message of movement, mass collaboration and sheer vitality. They didn’t need captions, but told rich stories through character and colour. The effect was enough to capture anyone’s attention.

Over the next few hours I found out where and why and by whom these photographs had been taken. They depicted the people and cause of Ekta Parishad an organisation that campaigns for the rights of India’s poorest communities, that fights for access to land and livelihoods and brings its supporters together in massive gatherings and marches to be noticed, to be listened to and to demand political response. It’s a patently passionate movement, in the sense that it relies on passion to maintain its protest. So perhaps it’s unsurprising that over the movement’s twenty-two year evolution, art (through photography, painting, theatre, music, dance) has been central to its form. How better to express that passion in the pursuit of its aims?

But as the AGM went on, as the need for change in the lives of those without land or access to resources was reported, as more stories of the plight of such people were told, the characterisation of these photographs surrounding us as a ‘useful strategy’ felt a little trite. These were more than pretty pictures. It seemed to me they were operating at a deeper level than that.

Listening to the reports of Ekta’s avowedly non-violent character and programme, its principle of ‘providing a platform for the voices of the oppressed’, the dynamic artistic demonstration of the cause and its followers had a clear purpose beyond simple depiction: bring the movement to life through provocative and striking images; make us see the vibrancy of its ideas as well as the scale of its campaigns; create iconic pictures that can unify and charm and intrigue; portray the hope instead of the anger, the solidarity instead of the suffering. In this there was an arguable link to that rich tradition of affective images which have done much more than represent a scene: the lone, unknown, man in Tiananmen Square standing before a line of tanks; Martin Luther King Jnr facing the Lincoln Memorial and a crowd of hundreds of thousands; Gandhi walking, Mandela’s fist rising. These and their ilk have worked as fulcrums capable of sustaining protests, remembering their power and enthusing new generations of supporters. Propel a message, represent a cause, perpetuate a swell of collective determination: art in every form can communicate all these messages.

Of course, they can manipulate too, which is hardly a new insight. Any history of propaganda would say as much. But with propaganda a dirty word now, how do the artists engaged in these movements see themselves when capturing or creating images for the cause? Are they conscious of any dilemma in the connection between ‘art’ and ‘protest’? If ‘photographers [or artists] of conscience,’ as Susan Sontag called them, are they somehow immune from the propagandist critique?

Perhaps George Orwell’s seminal essay on his motivation for writing (‘Why I Write’) offers some kind of answer. The artist, photographer, actor, creative writer might also seek to ‘fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole’ and accept the charge of propaganda without embarrassment. Propagating a message through art doesn’t have to be a challenge to some overriding artistic ethic of ‘balanced truth’. Orwell wrote that ‘the more one is conscious of one’s political bias, the more chance one has of acting politically without sacrificing one’s aesthetic and intellectual integrity.’ The political purpose he saw as the ‘desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s idea of the kind of society that they should strive after.’ There seems little reason to suppose the visual arts are any different from the act of writing.

As Action Village India’s AGM drew on, and the smell of south Indian food being cooked in the kitchens by the Madras Café crew breathed even more life into the photographs, the identity of two of the artists working with Ekta Parishad came to light. Simon Williams was the photographer whose work lined the walls. And Vikram Nayak was introduced via skype as a painter, photographer, cartoonist and film-maker who has actively supported the movement for more than ten years. It seemed sensible to ask them what they thought about their work and the wider question of art’s value in protest.

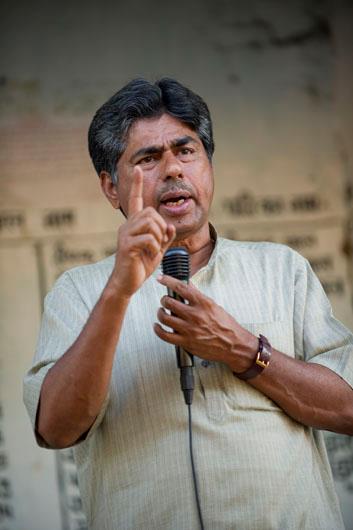

Rajagopal speaking to 25,000 people Janadesh 2007 India

Photo by Simon Williams

Part 2: The Photographer

Simon Williams says he was always entranced by India. Whilst still at art college in his late teens and early twenties, he would travel around the country drawing, painting and taking photographs. But it was in the spring of 2002 when he encountered a vision which transformed his relationship with both the people and place.

Photo by Simon Williams

In the hazy light of an early morning in March of that year, he watched on as a quiet Bihar village turned into a ‘pop up theatre’ as he calls it. A troupe of activists had rolled in, their banners proclaiming they were from Ekta Parishad.

Williams was drawn to the spectacle, a ‘kaleidoscope of colour, chanting, music’. He wanted to understand what was happening, who these people were, what they were hoping to achieve. Back in the UK, he volunteered with Action Village India, which supported Ekta’s campaigns. Then, a year later he returned to join one of their motorised protests.

Photo by Simon Williams

These yatras are ritualistic journeys, pilgrimages with convoys of jeeps and little vans carrying activists from village to village across India. They perform a double function of spiritual and political significance. They bring the cause to the people and reconnect the people to the cause. Each yatra is a mobile surge of investigation and protest, often changing course when it hears of some particular act of injustice.

This is what happened in Chhattisgarh state in 2003. The yatra Williams was accompanying shifted direction when news reached them that one of Ekta’s members had been axed to death in a remote area close to Pandaria. The convoy of campaigners rushed to the town and began a sit-in demonstration. Over several days the organisation was able to bring a sudden spotlight onto the killing and the endemic poverty of those in the region. It caused a political storm in the state, which eventually culminated in an official resolution that included land distribution to thousands of local families as well as compensation for the murder of the Ekta member.

Williams witnessed and photographed these moments of protest. His ability to capture the empowering impact of Ekta’s actions, the vibrancy and passion of those involved, was recognised by the movement’s charismatic leader. As they travelled together by jeep as part of that Chhattisgarh yatra, P.V. Rajagopal said to him, ‘You have the amazing ability to smell like a dog.’ It might have been an apt insult given the rough and ready conditions experienced on these demanding trips. But it wasn’t. Rajagopal thought Williams had the gift of being able to sniff out photographs that communicated the essence of Ekta’s mission and the people for whom it fought.

Photo by Simon Williams

‘As they travelled together by jeep as part of that Chhattisgarh yatra, P.V. Rajagopal said to him, “You have the amazing ability to smell, like a dog.”’

Rajagopal’s observation is borne out in the gallery of images Williams produced when Ekta Parishad decided to transform its acts of mobile non-violent protest. The Gandhian notion of a people’s march, footslogging hundreds of kilometres to portray the swell of public anger against endemic injustice, inspired Ekta to organise a walking protest in 2007. Named Janadesh ‘the verdict of the people’, 25,000 men, women and children marched 350 km from Gwalior to Delhi over 27 days. It attracted massive attention. The provocative non-violence of the march echoed not only the traditions of Mahatma Gandhi in that vital demand for independence, but also those rallies and public demonstrations that can transform the political environment of the day.

The images that Williams captured of that march portray the sheer scale of the enterprise, the intent, the passionate embrace of the aims of the movement with extraordinary power. They communicate the fundamental peacefulness of the protest with its pulsating colour and organised lines of humble demonstration. Threat and menace are missing in these pictures. They do not suggest a promise of violence that a huge crowd can sometimes evoke. Instead, they speak more of a determined resistance that’s all the more effective for its avoidance of direct conflict.

Photo by Simon Williams

The Janadesh march was only partially successful. Although the Government agreed to develop land reform policies to address the movement’s concerns, it dragged its feet on delivering its promises. When this became clear, Ekta sought to generate a second mass walk. Called Jan Satyagraha 100,000 people were to be gathered to repeat the earlier experience on an even greater scale. Williams followed them again.

Photo by Simon Williams

‘Jan Satyagraha is like two hands. With one hand we are promoting the concept of Ahimsa, Non-Violence. With the other we want to deliver justice to the poor. We are confident of delivering 50% of that message, non-violence. But that is a concept with no meaning and of no help to the poor. For them we have to deliver justice.’ P.V. Rajagopal

The march brought about a momentous agreement between the Indian Minister for Rural Development and Rajagopal acting on behalf of Ekta. Though it remains contentious whether this also will be fully implemented, it marked a distinct breakthrough for the landless movement. It was the ability of the march to make politicians take the movement seriously at a national level that was its pronounced achievement.

Williams’s photographs might have served to instil the public’s awareness of this significant moment with their capacity to evoke the grandeur of the marches. But his images are no less powerful when intimately focused.

The face of a child amidst a crowd of women whose attention is elsewhere; a simple donation to the cause from someone who can ill afford the gift; the leaders of the movement eating before a shrine to Gandhi: these are records of simple human moments which together underscore the movement’s purpose and method.

Photo by Simon Williams

Such very personal and individual encounters may explain the commitment Williams has shown in returning to record Ekta Parishad’s work on film for over a decade now. Reflecting on Janadesh and Jan Satyagraha he remembers Rajagopal saying once, ‘For me this yatra is a bit like peeling an onion. The more you peel, the more layers and skins you open, the more pungent it is and the more the tears flow.’ Often, it’s the deeper layers that Williams’s photographs help expose. And perhaps it’s the delicate individual images of those for whom the protests have been formed not the awe-inspiring vistas of miles of flags and marchers which are the more effective. Yet whether majestic vista or individual close-up the photographs are uniformly positive. They do not rely for their appeal on chronic suffering as so many ‘moving’ images appear to do. Instead, Williams reveals the depth of patience and collective resolve that defines Ekta as a movement.

Photo by Simon Williams

‘The more you peel, the more layers and skins you open, the more pungent it is and the more the tears flow.’

Being back in the UK doesn’t mean the experience of Ekta Parishad and its walking protests have become irrelevant. Williams says, ‘In an increasingly violent world, to see and experience the power of non-violence in action is very special. There is a real sense that the marches Ekta undertake are for all of us, all over the world. There are issues related to land that we can all benefit from understanding, re-addressing, re-thinking, re-examining, and resolving.’ He remembers Satish Kumar, a former Jain monk, Editor of Resurgence magazine and founder of the Schumacher College, speaking passionately at the opening of an exhibition of Williams’s photographs in August 2012. Kumar urged his audience to ‘see the connection between the protest action in India and our own reality in the West: to recognize the universal need for human dignity, to use our feet to walk and our hands to make things we need.’ He exhorted us all, whether in India or England, “to keep in touch with the earth, keep our feet on the ground, and to understand that economic growth means nothing unless we protect the land, water and air which are the source of all our wealth”.’

Simon Williams’s photography of Ekta’s persistent protests reinforces that message. The gallery of images he’s created over the years conveys the scale and nature and varied personality of the movement he supports. It emphasises the value of the medium of photography in protest without depicting suffering as a means to gain our attention. If anything, his photographs are celebrations of lives and the passion and purpose of a protest. They breathe some life into the human issues rather than simply serve to shock us into caring. And ultimately that feels more energising.

Part 3: The Artist

Ekta Kala Manch forms the cultural wing of Ekta Parishad. It’s described as the movement’s ‘singing heart and its creative spirit’. For the most part it organises the musical inspiration for the marches and protests, but it also operates as a means of communication, telling stories of people’s experiences through drama and song, relating Ekta’s message to the lives of others.

The visual arts also contribute to this endeavour. Perhaps they go further.

I couldn’t meet Vikram Nayak in person, but I was able to ask him some questions by e mail. He told me about realising Ekta Parishad’s aims through art as well as his sense of purpose in undertaking the work.

Vikram Nayak

Q. What role do you think your art has played for Ekta Parishad?

Visual images always play an important role in any kind of movement. They help build a bridge for communities. When you think about the size of India and its many variations of language, culture, tradition and lifestyles, which can change every 25km, they become essential.

Ekta Parishad knows this very well. They know how visual images can mobilise people. They’re very particular about storing and sharing these images. As Ekta reaches out to almost every part of India, trying to help and support landless people and organizations, they know they have to understand the local problems and the kind of help needed. And they have to be able to communicate Ekta’s value to everyone. The photographs, posters, films, art, all play a major role in that process.

It works in a number of ways. Ekta hold a lot of workshops, seminars, training camps and public meetings. These can only be of lasting significance if the people and local groups keep talking, sharing and debating the issues in Ekta’s absence. By leaving visual reminders of what was discussed and ideas of how to respond, Ekta can have a more lasting influence.

This is even more important when Ekta works in remote rural and forest areas. There are so many language differences and many are illiterate anyway, that the visual arts can help people understand the importance of the movement and promote the movement’s sense of unity. They can relate this to themselves and their own lives.

‘The press and media, who won’t travel deep into the forests to see for themselves, who won’t have a sense of the problems, rely on the images we produce.’

It’s not just for the rural communities that this proves useful. When we talk to people in the cities, they can see who we’re talking about and acting for. We need to gain the support of these urban communities too. The press and media, who won’t travel deep into the forests to see for themselves, who won’t have a sense of the problems, rely on the images we produce. They help inform them about the people who are represented by Ekta. You can’t imagine or understand Ekta without these visuals. Thousands, millions, from different walks of life, can fight for each other with these shared images.

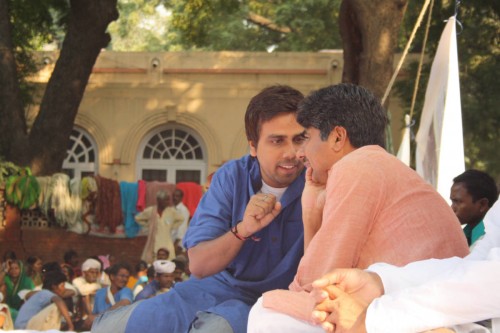

Vikram Nayak exhibition

Q. How did you come to be involved in Ekta Parishad?

My involvement with Ekta has lasted nearly ten years now. I used to work with under-privileged children in Delhi’s slum areas and I realised then that social activists rarely find creative people who understand their movement and message and can develop materials to meet their aims and needs.

Back then, around 2004, I knew about Ekta and attended a few public meetings organised by them. They had several volunteers who were good photographers or film makers or web designers but most were from other countries. They were producing materials for local farmers and tribes and I thought there needed to be some changes of style and layout if they were to be more effective. I met Ramesh Sharama, one of the leading people in Ekta, and then Rajagopalji and that’s how I became more deeply involved. They liked my ideas and in 2007 they asked me to make a film on the Janadesh march. I developed all the art designs, layouts, posters and banners. That’s when I became much more heavily involved and began to understand the movement much better.

Vikram Nayak and Rajagopalji

Q. Tell me a little more about how you’ve supported Ekta Parishad since then.

Your question suggests this is a one-way relationship: me supporting Ekta Parishad. But that’s not what I feel.

I have learned a lot from Ekta. I’ve seen a different India with them, a place which we can’t imagine in the city. My involvement helped me develop as a creative person and I see this impact in my paintings and other art work. Whatever I’ve done or am doing for Ekta is not for Ekta. My way of looking at society has changed and I feel the responsibility to use my skills to serve in some way. We always try to give meaning to our lives. My engagement with Ekta has helped me to find something of that meaning. So my support for Ekta is not just about art as the production of images. For me, it means much more than that.

Even so, over the years, as a visual artist, I’ve tried to use exhibitions as a way of communicating the land rights issue to an urban audience. People in the city often don’t think about the problem. They’re more concerned with wrongs that affect them, corruption, things like that. But my last exhibition brought hundreds of intellectuals together to support the movement and with them came newspaper and media coverage.

As a film maker I have a different role. My films are not just documentaries. They combine a message with facts. Sound and music are so important because I have to keep in mind the intended audience. These films are for illiterate farmers to college students, many who have no direct connection with the issue, and I have to communicate a clear message in a short time, 15-20 minutes at most. I’ve made about 5 or 6 films like this. They’ve been distributed widely and help share the message of Ekta and people’s involvement in the movement.

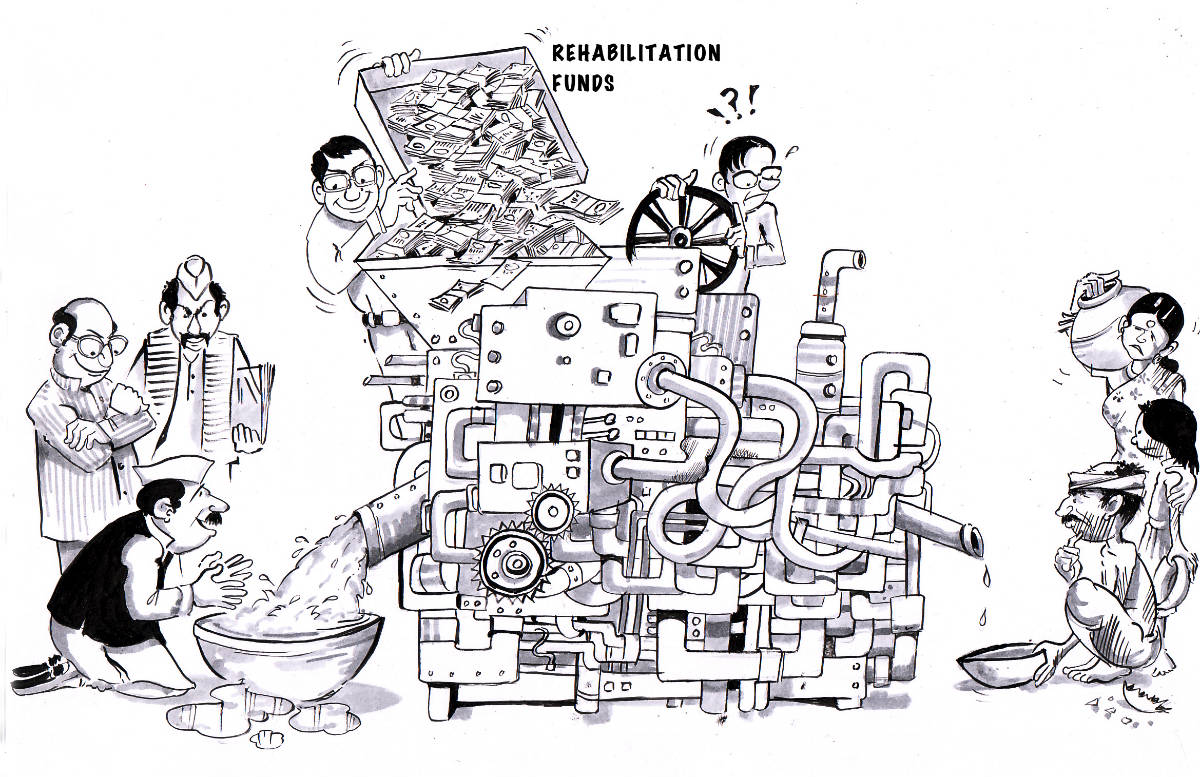

Vikram Nayak

As a cartoonist I use humour to raise serious questions. My cartoons are an easy way to suggest to people what the issues are we might think about. But for all of this you need understanding of the people and the cause. This can only come through working closely with the activists and the farmers and those involved in the movement at every level. You can’t touch the roots without spending this time. Every year I organise a culture festival in Chhattisgarh state. Ten tribal artists come and spend ten days with groups of school students. At the end of that time they all perform and exhibit their art work. It’s a way for students to interact with the people in these places, to reflect how their cultures are changing, to preserve the local forms of art and life. It’s a rich artistic process. But it also enables more people to use art to create questions for policy makers. That’s really important for me to be involved in the art of others, to facilitate this.

Part 4: The Context and the Image

Gandhi said there were seven social sins: politics without principles, wealth without work, pleasure without conscience, knowledge without character, commerce without morality, science without humanity, and worship without sacrifice. There may be an eighth: image without context.

The artists who work with Ekta Parishad are highly valued by the movement. So is their art. It’s a reflection of the cause. And to be a true reflection, an understanding of the context is vital. Otherwise the image becomes a cheap tool. Both Simon Williams and Vikram Nayak seem aware of this responsibility to do justice to the movement they have sought to capture in art. By becoming embedded within Ekta’s work did they assume a richer, truer appreciation of its purpose? Is that what art in protest can aspire to?

Some might argue that this instils the photographs and paintings and cartoons with an importance they don’t deserve. But when striving to communicate the soul of a movement the artistic image is highly significant. And perhaps its ability to portray and memorialise the moment of protest shouldn’t be underestimated, or at least it shouldn’t be discounted too abruptly as propaganda. Similarly, images don’t have to focus on suffering to be, as Sontag again said, ‘objects of contemplation to deepen one’s sense of reality’. That reality is as much about what is valued in life, what makes life bearable even in the midst of struggle, as it is about what burdens are borne.

Ekta Parishad are constantly engaged in the fight to have the reality of the landless and right-less poor of India understood for good and ill. Whether preserving access to resources threatened by the interests of the powerful, or gaining greater control and voice for the poor of India, the movement spends enormous energy communicating that mission. Williams, Nayak and many others seem central to that endeavour.

The latest film of Ekta Parishad and the march of 2012 was shown at the Solothurner Filmtage Festival in Switzerland in January 2014.