Amir Amirani’s documentary We Are Many investigates the unprecedented worldwide protests against the Iraq War in 2003, when millions across 60 countries marched for peace. Reviewer Christopher Davis finds not only an exposé of the war, but a salute to the spirit of protest.

In March 2003, when President Bush sanctioned the invasion of Iraq, I was 16. Now, looking back, I realise how narrow my perception of world affairs was.

Perhaps it was just a matter of my age, and that I consumed news without chewing. I’m sure I would not have been the only one in those months lured into feeling as though the intervention were an act of deserved retaliation.

I watched the attacks on the World Trade Center towers 18 months previously as a 14-year-old through disbelieving eyes, and I tried to understand how it could have happened.

Again, I would not have been alone in watching and watching and watching again as the planes slammed into the glass walls of the towers in a giant ball of flames.

I remember, at the instruction of my father, buying and keeping hold of the newspaper from September 12th – I still have it now, pressed beneath a mattress in a plastic wallet with other clippings.

I remember the image of Mohamed Atta a few pages in, his grave eyes and dark hair. It was a logical course of events that followed, I believed; events that seemed to culminate naturally in airstrikes on Baghdad on a March evening in 2003.

The reason I call all this to mind is because what I distinctly remember about the beginning of the conflict in Iraq is the sense of excitement and intrigue it conjured in me. When the first bombs fell and the news stations streamed footage of the Baghdad skyline lit up orange by airstrikes, I was with a school friend.

On the little television in my bedroom we witnessed the bright white tails of the bombs scream downwards before microphones picked up the deafening bangs that rang out across the city. It was exciting. I recall thinking two things: that, on the one hand, it was retribution for the lives lost in New York and that, on the other, the strikes must have been deadly accurate to hit only their military targets.

That is how I received the conflict, as a series of events that somehow began with 9/11 and led to the invasion of Iraq a year and a half later. Had someone asked me to explain the link, I would have struggled to do so. But I gathered that there was a logical reason behind it, even if ultimately that reason was beyond my grasp. (In hindsight, I think that – shameful as it is – I had not yet been weaned from an imperialist British conviction about the supposed barbarity of the Middle East. They had attacked Us. Somehow it followed that We should react in turn.)

I was a teenager and I was impressionable. The wool was pulled over my eyes, I think, as it was pulled over the eyes of many others.

Opinion polls suggested that the British government was not acting completely of its own volition. It had not framed the proposed intervention as a direct response to 9/11 per se, but widespread Middle Eastern threat was a deeply embedded component of the rhetoric.

“Why does it matter so much?” Tony Blair had asked in a rousing address to the House of Commons, the day before the conflict began. And then, in answer to his own question, the Prime Minister had said:

“Because the outcome of this issue will now determine more than the fate of the Iraqi regime and more than the future of the Iraqi people, for so long brutalised by Saddam. It will determine the way Britain and the world confront the central security threat of the 21st century; the development of the UN; the relationship between Europe and the US; the relations within the EU and the way the US engages with the rest of the world. It will determine the pattern of international politics for the next generation.”

Blair fought up to the last minute to convince MPs, who had been granted an historic vote on the matter – such was the level of objection.

After what was a relentless scramble for support, the Commons voted unanimously in favour of military action.

Alongside the parliamentary debate, there was huge public outrage. In February 2003, London was transformed into a swarm of protest. I remember it well and, retrospectively, would have loved to have been part of that mass march on Whitehall.

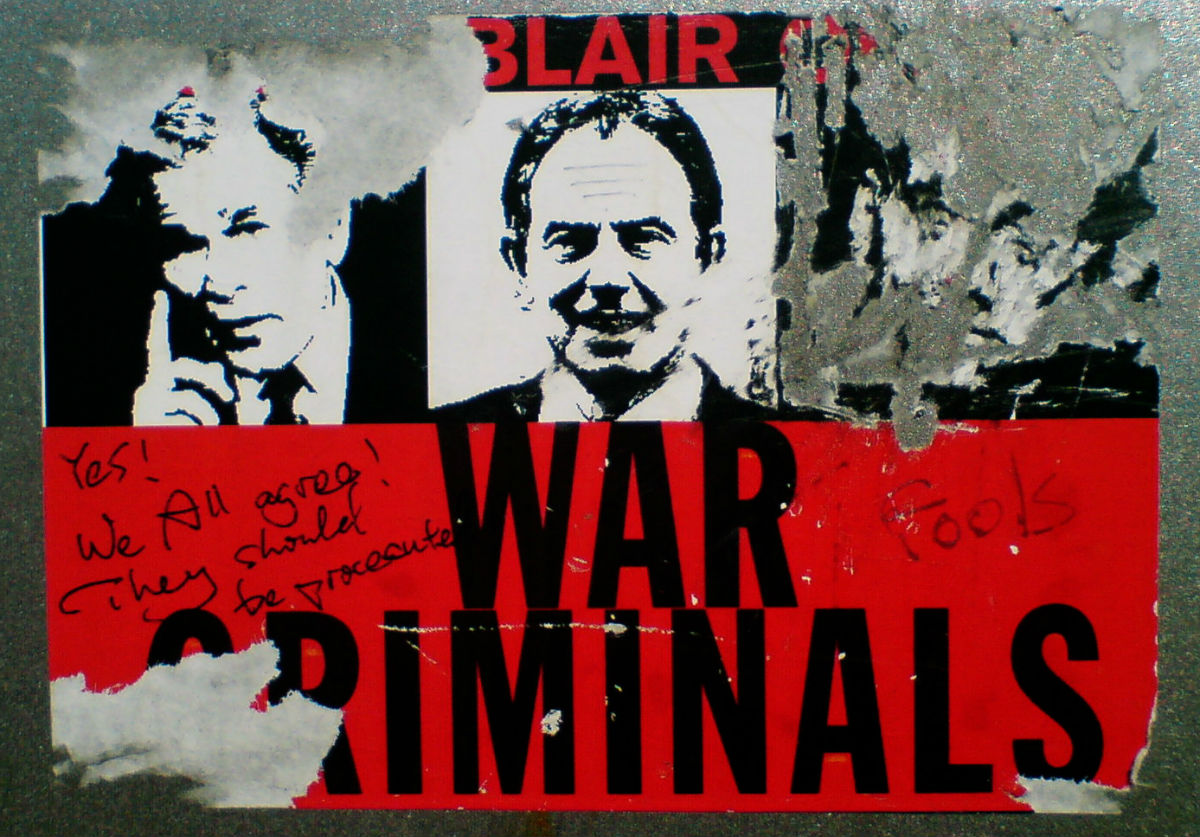

Horns blared and the sound of voices on mass was chilling. Banners showed simple messages: “No War on Iraq”; “Make Tea Not War”. It was the culmination of an unprecedented protest movement organised by the Stop the War Coalition, a body that formed in the shadow of President Bush’s declaration of a “war on terror” in 2001. The march played a key part in prompting the Commons vote.

London did not protest alone: it was but one part in a mammoth mobilisation of dissenting voices around the globe. There was no ignoring it.

Looking back, the two narratives seem hardly to fit together: the overwhelming outrage at the plans to engage militarily with Iraq and, conversely, Bush and Blair’s calm, unflinching resolve to do so anyway, with or without a UN Security Council resolution.

The tone of the two strands was so at odds. And yet they were so tightly bound. The protest movement emitted a voice so loud that it could not be ignored, but the ultimate decision to go to war in Iraq was a fatal pinprick to what had been a steadily inflating balloon of global anti-war sentiment.

The harshness of the contrast between the control of the political rhetoric and the riotousness of the protests made it seem like two entirely different matters, mutually exclusive. They were two different landscapes.

Amir Amirani’s carefully assembled documentary, We are Many, retraces the steps of those years following the attacks in New York.

On the one hand, it tells the remarkable story of the massive anti-war protest movements: the extraordinary support it garnered from the beginning in the lecture halls of University College London, its drawing of mass support from those who had never taken to protest before. Some of its main architects – Jeremy Corbyn MP, Anas Altikriti and so on – talk on film of their astonishment at the surge in opinion.

On the other hand, it revisits the cut-throat arena of international relations in those pivotal months and years, during which time truth and lies were intimate bedfellows.

Not only does the film bring together an extraordinary gathering of notable people, all of whom have something meaningful to add to the debate, it also manages to blow away much of what is left of the smokescreen.

True, developments in recent years – the ongoing Chilcot Inquiry, for one, and the gradual coming to light of key details – have all but confirmed beyond any reasonable doubt the unlawfulness of the war. But it takes us beyond obvious inferences and the condemning opinions, and finds its own defiant tenor.

The sometimes raucousness of its musical score, its irreverent packaging of Bush and Blair sound bites, its breadth of contributions, further inserts a thorn into the side of the Iraq conflict’s ethics by keeping its voice of protest loud and clear. Which is to say that the film is more than a sober litany of talking head interviews: it is counter-knowledge.

Viewers watch in the auditorium appalled, moved by the frankness of the material. The film presents an extraordinary archive, beginning with a thorough examination of the years 2001-2003. It casts a light on the doubts and the inconsistencies – the lies – that were both covered up and not-so-covered up during that time.

There was a cloud hanging over the proposed removal from power of Saddam right from the start. Public doubts over the conviction that Iraq was holding, or developing, weapons of mass destruction were not allayed by the publication of a report in September 2002 that brought little new evidence to light.

The findings of the “dodgy dossier”, compiled by the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC), were later criticised for consciously trying to strengthen the case for military action against Iraq.

The document was a curious one, certainly. In its introduction, Tony Blair stressed the “serious and current” threat Saddam posed, before the report went on to suggest, alarmingly, that Saddam was “ready to use [WMD], including against his own populations, and is determined to retain them”.

Much was made of the detail that Saddam was able to mobilise and deploy weapons in the space of forty-five minutes. Britain’s broadsheets lapped this up, drawn in by the sense of alarm it created. “Just 45 minutes from attack,” a Daily Mail headline read shortly after the report’s publication.

In the months leading up to March 2003, a different type of war took place to the one that would ensue afterwards. It was a war of information. Or rather, it was a war of misinformation.

John Le Carre, ever-insightful and sage on camera, speaks of the false and misleading knowledge produced by the British government in late 2002 and early 2003. The novelist talks of how little information was given to the public, but how it was always suggested that “experts had seen this” and that “reliable sources had seen that”.

It was deemed to be information not suitable for public reception. And, of course, it was not suitable because it was, to a degree, not reliable information at all. “Intelligence has become available from reliable sources which complements and adds to previous intelligence,” the JIC report read. “[It] confirms the JIC assessment that Iraq has chemical and biological weapons.”

Later, an Arms Control Association fact sheet would suggest the following about subsequent weapons inspections: “The inspectors did not find that Iraq possessed chemical or biological weapons or that it had reconstituted its nuclear weapons programme.” The British government’s tactics, then, would look for all the world to have been centred around carefully couched words, smoke and mirrors.

Photo by Fabio Venni

Behind the rhetoric, other conversations were taking place.

In leaked correspondence between David Manning, Ambassador to the US, and the Prime Minister’s assistant, Matthew Rycroft, dating back to a July 2002 meeting in the oval office between Bush and Blair, it is suggested that military intervention had already become a firm part of the President’s strategy.

“There was a perceptible shift in attitude,” it reads. “Military action was now seen as inevitable.” Options had been flirted with at the meeting, timeframes mentioned. And then, damningly, the following: “There was little discussion in Washington,” Rycroft had written, “of the aftermath after military action.”

Leading up to March 2003, then, it would seem to have been a matter of the Prime Minister fending off the staunch objections of the public, all the while knowing his own thoughts on the matter. Or, even if he had no desire for military action, his hand was all but forced by his American counterpart.

For Blair, irrespective of the outcry, the British stance was already finalised. A memorandum sent to the PM in September 2002 from Rycroft makes it clear how aware the government was of public opinion. In anticipation of a press conference, the Prime Minister had been briefed with answers to “difficult questions”.

Over and over, the document reiterates what would later ring out as lies: “This is not just about Iraq,” it reads. “So the big issue is WMD, not Iraq.” “As I said, the real issue is not Saddam but WMD.” “No decisions have been taken.” And so on.

On film, Blair’s voice is always full of conviction, which adds to the sense of discomfort as evidence is stacked up against him. Experts, declassified documents, hindsight – all expose his decision-making.

There were dissenting voices in parliament, of course. Clare Short, then Secretary for International Development, speaks in interview openly of her sense of being lied to by the Prime Minister. She resigned after the conflict began, in May 2003.

We see on film, too, Robin Cook’s famed resignation from the Commons on March 17th. The then Leader of the House of Commons’ gentle yet impassioned address, in the context of the film, stands out like a lone voice of political sincerity in an otherwise frenzied debate. Cook, calm and grave, spoke of “a war that has neither international agreement nor domestic support” before resigning from his post.

Even if the mass objection to military intervention failed ultimately to prevent it happening, there is little question that the protests left a powerful legacy. Indeed, the film’s packaging of footage from those months in early 2003 demonstrates the resoluteness of human spirit and, remarkably, the ability to mobilise an international protest movement.

The gatherings in London, Rome and Madrid are known to have drawn numbers well in excess of a million in each city. Yet the protests began earlier in the Pacific and, with the turning of the globe on February 15th, they worked their way across Asia, Africa, Europe and onward to the Americas. (We also see the protests at the McMurdo research station at the tip of Ross Island, Antarctica, where a small gathering joined arms and formed Gerald Holtom’s peace sign. If more symbolic confirmation were needed, it was a truly global campaign.)

There are moments of genuine delight in the film, such as when one hears the account of Will Saunders, who scaled the sails of the Sydney Opera House and daubed with paint the slogan “No to War” in letters so large that footage from above framed them beautifully.

The blood-red paint, scrawled on the pristine white of the tiles, gave it the air of a ransom note. As police arrived, Saunders was just about to complete the final letter. “Can I just finish it off?” he reportedly asked. “I think you’ve done enough,” the officer replied, leading him away from the scene.

More than a decade on, it is compelling to hear the testimonies of people like Saunders, accounts that reflect upon the unprecedented swell of outrage – in Saunders’ case, almost as though he himself could not fully explain it.

The trajectory of the film’s narrative is interesting. As we see the inexorable increase in momentum of the Stop the War Coalition and its counterparts, which garnered unforeseen support in those months, it feels for all the world as if it will achieve its goal.

The film’s constant countdowns to the start of the war – 18 months until war; one year; six months; two weeks; two days – seem hardly to register, such is the buoyancy and the doggedness of the movement. One knows what ultimately happened next, but still there is hope that the movement will prove to be successful in its aim.

Photo by James M Thorne

A significant shift takes place around the halfway mark when, naturally, the countdown clock reaches zero and all the optimistic clamour of the protestors is suddenly blown away by the sound of bombs falling on Baghdad. The tone is different then.

No longer is there a buzz of enthusiasm; there is just sense of deflation. (One can feel this palpably inside the cinema auditorium too. The audience seem suddenly crestfallen.) Again, we all know what happened, but reliving it is no easier now.

I had felt uplifted in those early minutes of the film and then, with a bang, it was gone. There was only anger left provoked by a moment when photographs of civilian casualties in Iraq – maimed, bloodied, dead – are interspersed with footage taken from the controversial speech George Bush gave at the Radio and Television Correspondents’ Association (RTCA) dinner in 2004.

Bush joked about the search for WMD, showing snapshots of himself and his cabinet mockingly searching the oval office. “No weapons of mass destruction here,” he remarked, showing a photograph of Dick Cheney seemingly looking behind a curtain or under a desk: a picture of a wounded child on the screen.

The RTCA guests were in stitches: a young girl with single tear at her cheek. Bush continued to make fun of Cheney, Condoleezza Rice, his inner circle, showing more pictures of them in various comic positions: footage of a bomb devastating a building. It was all a game.

I always found something childish and anodyne about Bush when a smiled curled at his lips. But when the grave consequences of his actions are played out like this, placing his jovial words alongside pictures of horrific injuries he authorised, his wry smile takes on a sinister air.

So too do the words of Blair, speaking before the Commons in the final days before the intervention: with retrospect, we know the conversations the Prime Minister had already had. It makes the emotional words that come out of his mouth feel harrowingly underwritten by deceit. His distinctive, economic delivery sounds so villainous now.

More than a decade on, there remain unanswered questions about the Iraq campaign. Not so much about the decision to go into Iraq, but about the extent of the deception. It is like a magic trick: one knows there has been a sleight of hand, but absolute clarity remains out of sight.

That Tony Blair is barely able to return to the country he once governed is telling, though. Minds have long been made up. (Unsurprisingly, Blair declined an interview for the film.)

That the former Vice President, Dick Cheney, meanwhile, is shown being hounded wherever he goes, suggests the heights to which the outrage has soared in the intervening years. Arriving for an evening reception, Cheney is met by familiar protesters, who point and scream at him: “War criminal! War criminal!”

For all the shadows that keep the full picture of the 2003 conflict from coming to light, a film of this nature feels necessary. Not as some parsimonious anniversary of the protests, but as a genuine attempt to create a counter-knowledge, to connect up the dots in what was, and remains, a war based on smoke and mirrors.

Hearing the voices of insiders like Hans Blix, whose report to the UN Security Council in February 2003 conflicted with Bush’s appraisal of Iraq’s military threat, provides a counterpoint to the polished lies of the former President.

There is also an interview with Richard Branson, who, with Nelson Mandela, had seemingly attempted an unlikely and perhaps ridiculous coup of his own just before the declaration of war. Branson had planned to fly to Baghdad with the former South African leader in order to persuade Saddam into towing the line with the US.

Amirani attempts what would seem an impossibility: to render artistically the outright messiness of the war, to bring together on film what are, respectively, political and defence issues, matters of international diplomacy, human rights abuses, disparate protest movements and personal stories. It is something of a feat, for We Are Many is not only an exposé of the war, but a salute to the spirit of protest.

It is gripping to observe the way that mass anger was channelled in early 2003 into a hugely organised protest movement. Hossam El-Hamalawy, an Egyptian activist, talks candidly on film about how 2003 paved the way for the Arab Spring eight years later. Tahrir Square hosted protestors in 2003, just as it did famously in 2011.

The film is held together by the sincerity of its interviews by those who clearly invest faith in sharing honest opinions. Hamalawy is one of them. He talks about his early frustrations at how Western capitals could organise and stage these types of protests. ‘Why couldn’t Egypt do the same?’ He asks himself.

Lawrence Wilkerson, meanwhile, former chief of staff to Colin Powell, has not shied away from comment in the years following Iraq. Wilkerson has been quick to criticise the American government’s production of intelligence before 2003, and has admitted his own role in this.

Here he is frank once more, stating clearly that he would do it differently if given the chance. David Blunkett, by contrast, Home Secretary in 2003, appears towards the end of the film and cannot bring himself to indict himself or his former government colleagues. His reticence suggests almost as much as open and honest words would do.

One of the hardest things to comprehend with The Iraq War is the vastness of the territory it covers. It was, and has continued to be, a matter of politics, international law, human rights and protest – all of which connect with each other awkwardly.

The footage of the war itself is so far removed from the cool green interior of the House of Commons. The blood-and-dust faces of Iraqi casualties jars with George Bush’s crisp black dinner jacket at the RTCA dinner. And the energised hum of protesting voices, which, across the globe, formed a universal language of dissent in early 2003 – that raucous, primitive hubbub of human ire – is horrifyingly at odds with Bush and Blair’s cool declaration of war.

The film brings these disparate elements together within a single frame and, in doing so, in pitting discordant voices against each other, one is left with an overwhelming impression that something very, very amiss was done in our name.

It is left to the likes of well-known figures like musician Damon Albarn and actor Mark Rylance to set the final tone for the film. Both speak in the final stages with terrible sadness at the ultimate failure of the protests they were part of.

Albarn questions, with hindsight, whether a more committed approach would have changed the course of the events. “What would have happened if we came back the next week?” he asks, raising a challenge for any protest. Rylance’s measured, quiet tone, meanwhile, epitomises the overwhelming sense of deflation the film arrives at.

All the early buoyancy comes to nothing, after all. In the end, the fact of going to war always, inevitably, overrides the fact that many millions were vehemently opposed to such violence.

Photo by fotdmike

MORE: