A never-ending exile

When twenty-three years ago Bechir agreed, like all his fellow soldiers in the Saharawi People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), to put away his weapons and bring to an end a twenty-year war waged against Morocco for the liberation of Western Sahara, he still had some doubts as to the wisdom of this decision.

He knew that the diplomatic route would be full of obstacles and pitfalls, but he hoped that the commitment of the international community could lead to concrete results, without more bloodshed.

Text Photography and Videos by Tomaso Clavarino

But since 1991, the year of the UN-brokered ceasefire that should have paved the way to a referendum for the independence of this part of the desert, nothing, literally nothing has changed for the Saharawi people.

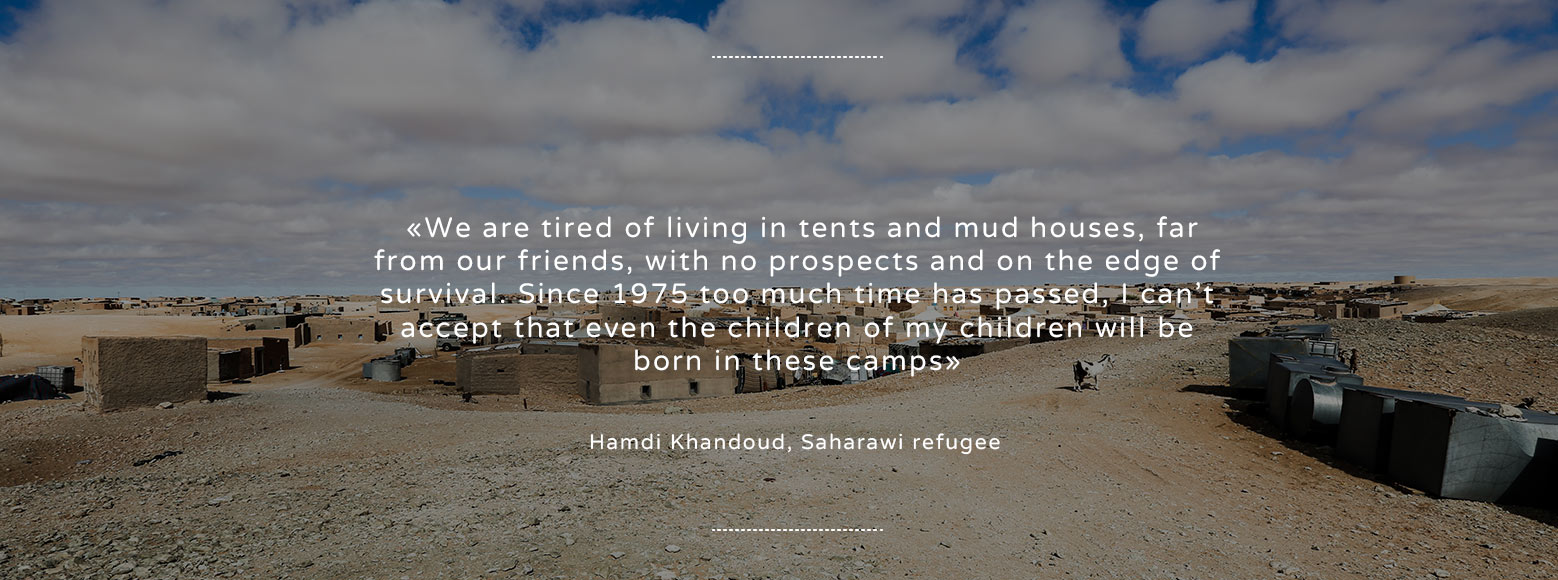

Bechir’s children were born in the camps to which his generation was forced to flee. They live in tents, brick houses of sand, in one of the most inhospitable areas of the whole Maghreb, in southern Algeria, between Tindouf and the border with Mauritania. A place that is a flat and stony desert, cold in winter and stifling in summer, often buffeted by strong winds that fill eyes, mouths and houses with sand.

Here, among goats forced to eat plastic because they have nothing else available, an unemployment rate that grows from year to year, the Saharawi population, made up of about 170,000 people, is still forced to live without a future, without prospects.

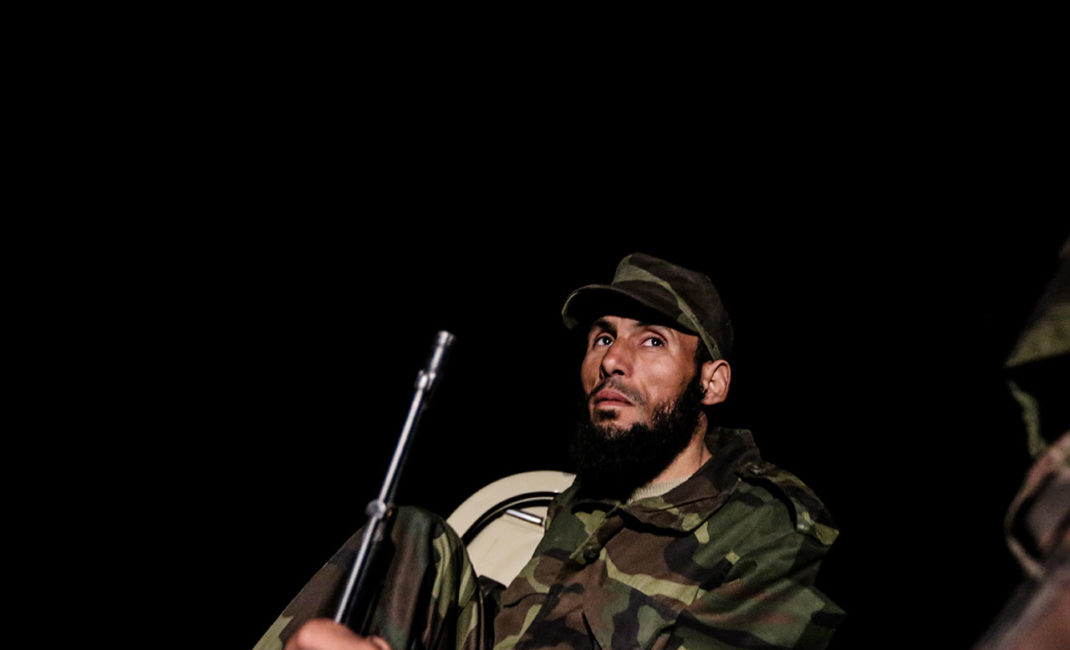

The failure of the international community is visible to all. Although a mission, MINURSO (United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara) was created especially to give life to a referendum, in 23 years it has failed to produce one. Forty years on from the beginning of their exile in Southern Algeria, even the Saharawi wonder if it is still worthwhile to wait or whether it is appropriate to take up arms again to recover what, according to what they say, belongs to them. And so the military manoeuvres in the desert began, with inspections of various bases of the Saharawi People’s Liberation Army by the leadership of the government of the Polisario Front.

Dreaming a nation

Mohammed Lamin Elbouhali, Defense Minister of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), does not mince words to explain the thought of the Polisario Front, the political arm of the Saharawi people, on the issue: “We can not, and do not want, to wait any longer, our patience is over.”

“We accepted the conditions imposed by the international community, we have agreed to dialogue, but it did not do anything. Morocco continues to provoke and not to accept or even to discuss the electoral base for this referendum in which now no one believes. We are ready to take up arms to regain our land”.

You can breathe the impatience going around among the refugee camps. You can breathe it in Smara, in Rabouni, in Auserd, you can breathe it talking with seniors who participated in the bloody war against Rabat, but also exchanging views with those young people that have never seen their homeland but who are aware that in these fields, for them, there are no prospects.

Text Photography and Videos by Tomaso Clavarino

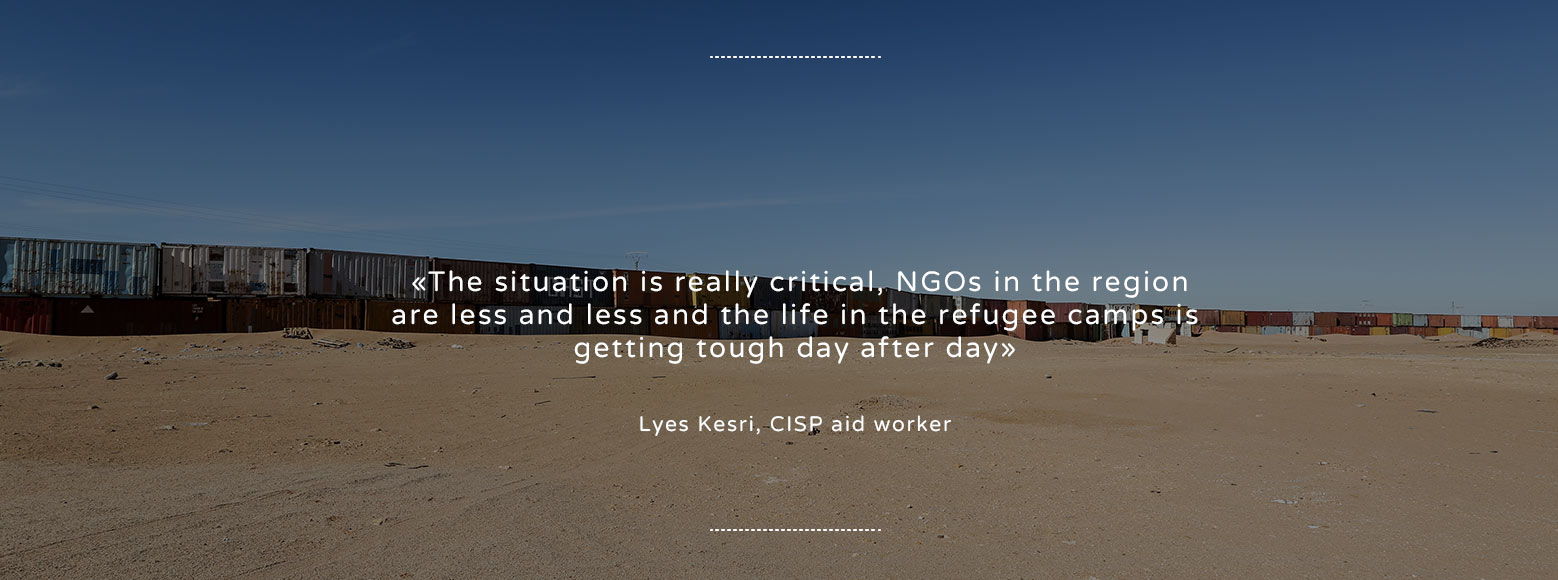

The collapse of humanitarian aid

For decades the Saharawi population has depended solely on humanitarian aid. Food, medicine, clothes, everything comes to the refugee camps in containers from the four corners of the world.

But due to the economic crisis that has hit Western countries in recent years, to the explosion of war emergencies in other regions, and to the fact that this crisis, the crisis of Western Sahara and the Saharawi people, has continued for four decades, latterly humanitarian aid has collapsed.

“In the last four years the donations and the commitment of the international community have been reduced significantly,” – says Brahim Mojtar, Minister of Cooperation. “ We can even say they have plummeted dramatically. This is hugely damaging for a population like the Saharawis that depends for all aspects on humanitarian aid. Eight million euro per year would be enough to feed everyone, a pittance, but we find it hard to scrape it together. But the real danger for us is not to die of hunger, the real risk for us is falling by the wayside. Such a long crisis, a conflict that has continued for so many years, inevitably leads to lower interest from the international community towards our cause and our sufferings and this is just what Morocco wants. And that’s why we, as Polisario Front’s members, as Saharawis, can not risk waiting any longer in vain, unable to see our friends and our relatives who live in the occupied territories beyond the Moroccan Wall”.

Illustration by Norma Nardi

The wall of shame

Two thousand seven hundred kilometers of mud, sand and barbed wire stretch, from the Algerian border to the Mauritanian one. On one side are the “liberated” territories controlled by the Polisario Front, on the other the “occupied” territories under the reign of Mohammed VI.

On one side lies the desert, occasional villages, nomad tents, and nothing more, on the other there are rich deposits of phosphate, some of the most fish-rich waters of the planet and oil, so much oil that the US oil company Kosmos will shortly begin drilling offshore. In the middle is a strip of land that is one of the most heavily mined in the world, which has already claimed 2,500 victims, both military and civilian.

By some estimates the number of land mines and anti-tank devices placed near the wall, on the side controlled by the Polisario Front, could be around 7 and 10 million. Among these, thousands of unexploded ordnance and cluster bombs that every year injure, and kill, dozens of people, mostly nomads that in those areas graze their flocks, and children who mistake the ordnance for toys.

“I was grazing the goats in the area close to the wall, not far from Mehaires, it had rained so I had to move a bit forward because in that area there was more water. I placed my foot on the ground, I realized I’d stepped on something but I couldn’t do anything. And so I lost a leg” says Embarel Mohamed, in his grocery store in the February 27 refugees camp. The conflict between Morocco and the Polisario Front, albeit muted by a shaky cease-fire, continues to claim victims then, in the silence of the media that seem to have forgotten about a crisis for which the entire international community has a huge responsibility.

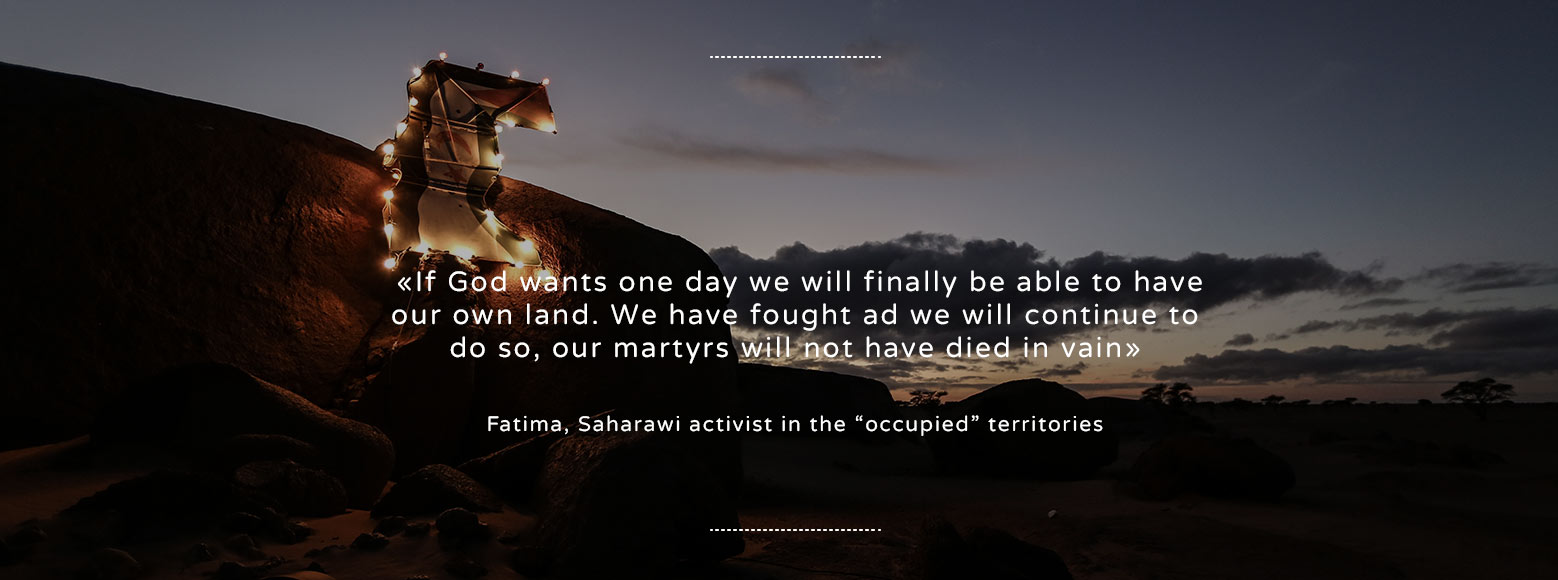

In the “occupied” territories, so formally in Moroccan territory, the Saharawi community – numbering over 300 thousand people – lives scattered among the cities of Layyoune, Dakhla, Smara, Boujdour, discriminated against by the institutions of Rabat and the Moroccan population. Violence against the Saharawi by security forces in Morocco is almost daily. Those Saharawi that demonstrate in the street for the independence of Western Sahara, about the difficult living conditions and against the repression are beaten, arrested, often tortured, and finally sentenced by military courts with up to life imprisonment.

During the war thousands of Saharawis disappeared into thin air from the territories under Moroccan control, and many of them, almost four hundred, are still missing. But the disappearances of activists are not a thing of the past. Associations like Afapredesa (Asociación de Familiares de Desaparecidos y Presos Sahrawis) denounce new and continuing disappearances of activists, protesters, youngsters and the elderly. Many of them try to escape and get over the wall that separates Morocco from the part of Western Sahara controlled by the Polisario Front, but few succeed in doing so because the control of the Moroccan government is rigid and the area is full of dangers, primarily mines. Despite the complaints and appeals of several NGOs and associations that invite the international community to take action against Morocco for human rights violations, the MINURSO mission is one of the few in the world that has no power on human rights issues.

A new challenge

Only sand, rocks, and the dark. And nothing more. And it is in this darkness that envelops the night in Western Sahara that smugglers, drug traffickers and terrorists prowl, in addition to the old cars of the SPLA. Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the Movement for the uniqueness of the Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), Ansar Eddine, are just some of the acronyms that in recent years, have seared this strip of Africa with bombings and kidnappings.

They exploit these stretches of sand, these no man’s lands. The meeting with the jihadist for the Saharawi community was sudden, shocking. One night in October 2011, a jeep, gunfire, and three volunteers, two Spaniards and an Italian woman, were kidnapped and taken at full speed across the border with Mali. This kidnapping was to have a happy ending (the three were released after nine months of imprisonment) but it represents an important watershed in this arid land already stricken by years of conflict.

Text Photography and Videos by Tomaso Clavarino

“Before the kidnapping of the three aid workers we thought that the phenomenon of Islamic terrorism wouldn’t have touched us” said Sidi Augal, the commander of the Fifth Military Region “We have always had only one enemy: Morocco. But now we have to fight on two fronts: to take back our land illegally occupied by Rabat and to stop the threat posed by terrorists”.

In this area, where poverty and unemployment go hand in hand with the lack of interest of the international community, terrorists have found an ideal breeding ground to grow and propagate their ideas. The Polisario Front and the People’s Liberation Army Saharawi know that this terrorism is a threat not only for the region but also for the stability of a community that has been living in extreme difficulty for four decades.

A disputed desert

“The risk is that terrorist groups could be able to infiltrate refugee camps, mosques, and do proselytism, especially among the increasingly young people, who wonder what their future could be, far from their land and away from families and friends living in the territories occupied by Morocco” – explains Brahim Ahmed Mahmoud, Secretary of Security for the Polisario Front – “the Saharawi are in the midst of a whirlwind, in an explosive area, and they are the only victims of this situation.

We do our best, with the means at our disposal, to check the area and ensure their safety, but until we get back our country, break down the wall that divides the Moroccan Western Sahara and embrace our brothers who suffer repression by the security forces in Rabat, everything will remain more difficult”.

Patrols day and night in the desert, roadblocks, checkpoints, stocks for the few Westerners who, despite calls by the various governments to abandon the region, have decided to continue working there. These are the means at the disposal of Polisario Front to try to curb the advance of terrorism in a region of porous borders and arid expanses difficult to control.

This terrorism has touched the Saharawis deeply. In the group who kidnapped the three aid workers, there were some (certainly one) of their own people. This has prompted Morocco to accuse the Polisario Front of backing the jihadists. Allegations were promptly refuted but the episode has made it even harder for the international community to commit in the region.

Forty years have passed but little or nothing has changed for the Saharawis. New challenges are piled on to unresolved conflicts and tensions are never silenced. The impatience of the youth mounts and the threat of a resumption of the armed conflict against Morocco no longer seems to be just a bogeyman used to attract the attention of the international community.

This article was first published by Isacco Chiaf

Isacco Chiaf is an Italian graphic designer based in Brussels. He is interested in journalism, interactive environments, live performances and experimenting new visual contexts. His projects bring toghether performances, web, social media, and data journalism to explore storyteling and visual narratives.

Isacco Chiaf is an Italian graphic designer based in Brussels. He is interested in journalism, interactive environments, live performances and experimenting new visual contexts. His projects bring toghether performances, web, social media, and data journalism to explore storyteling and visual narratives.