The Syrian playwright sets ‘Goats’ in villages where families of dead soldiers receive the animals as compensation. She tells Charlotte Bailey about the grotesque realities of normalising war and the dangerous stereotyping of Syrian refugees.

“We are happy to announce news of a generous initiative… A mountain goat for the family of each martyr,” the mayor of a village in Assad-controlled territory announces in Goats at London’s Royal Court Theatre.

The “goat-for-martyr” project was real, says Syrian playwright Liwaa Yazji. The initiative, she explains, is part of Assad’s “propaganda machine”, encouraging the celebration of those killed in the war. It struck her as grotesque and theatrical.

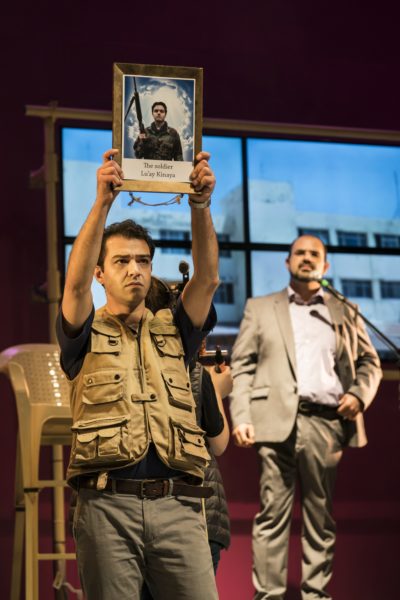

Credit: Johan Persson

Yazji’s play is a meditation on the role of propaganda in the Syrian civil war, posing the question: How deep does indoctrination go?

Most people accepted the goats they were given, but was it out of fear, economic necessity or a genuine celebration of martyrdom?

Yazji points out that this is not new. In Syria the media was always tightly controlled under Assad.

“I’ve lived with this all through the years. It existed way before 2011, but things were not as extreme as they are now.”

And things really are extreme: authorities in government-held areas of Syria forcibly restrict news coverage. False statements and propaganda frequent state-run outlets, and all media is subject to official censorship.

Ever-present in the play are TV screens projecting government-approved news, as the glamorous anchor of the state broadcaster lavishes sycophantic praise on the regime.

Credit: Johan Persson

In Goats, the government’s message is pervasive. At the funeral service held for several killed soldiers, the chair of the local party says to a bereaved wife: “What an honour for his young bride! You must be so proud now his home is in the heavens.”

Credit: Johan Persson

A villager says: “One thing I know for sure is that my son is no more important or precious than the nation.”

The one dissenting voice, a heartbroken father and once-respected teacher in the town, speaks up: “I am not here to celebrate. You know that very well. My son is dead.”

The father is driven to convince the others of his belief that: “Our children are not martyrs, they are cannon fodder.”

As the play progresses it makes clear that the loss of countless young lives is nothing to celebrate.

“Do you know what the body of a martyr looks like? When an RPG hits a tank, what happens inside? The soldier melts. His body fuses with the tank and ends up in a lump of stinking metal that you cannot prise apart.”

The stories from a soldier returning from fighting for the regime reveal that many soldiers did not die heroic deaths. Suicides and accidents are common, and all deaths are gruesome and painful.

Credit: Johan Persson

He furiously dispels the myth held in the village that regime soldiers are beyond reproach.

While much press coverage has focused on sexual violence by ISIS, a report published last year reveals that pro-regime security forces have been strategically committing rapes in the midst of the conflict.

Although there are unavoidable descriptions of horrific violence in the play, at its heart it is about ordinary people trying to survive in extraordinary circumstances.

Yazji says: “I didn’t want to knock on doors saying the same thing about Syria that has already been said.”

She also set out to avoid stereotypes of Syrian people that would have detached the audience from the action on stage:

Credit: Johan Persson

“I don’t want people to think, ‘This is happening in a place I don’t know, and the people are different from me so it’s OK’. This is not OK to happen anywhere. It is not OK.”

When asked what she would like people to take away from the play, she says: “To question, always question, what you are told by your government.”

And while media coverage often focuses on refugees and those trying to leave the country, perhaps to Europe, Yazji urges: “Think of Syria, and those who are still trying to live in Syria.”

- Goats runs at the Royal Court until December 23.

MORE:

How Banksy’s art became the symbol of the #withSyria campaign

What do 270 migrant and refugee interviews reveal about Europe’s approach to migration?

For stories like these direct to your inbox every month, subscribe here.