In 2020, a long-running dispute between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave escalated into war. After a nine-month blockade from December 2022, a military offensive by Azerbaijan forced 100,000 ethnic Armenians to evacuate their homes. But the conflict has received little international attention. Our writer asks why this crisis has been ignored by the international community, and tells the stories of those displaced, asking what hopes they have to return.

“There was this silence, I couldn’t understand it,” says Lusine Minasyan, whose young son, Artak, is playing with the Snapchat filters on my phone as we speak. “I had this feeling that the international community didn’t care about us having to leave our ancestral land.”

This will be Lusine’s second winter away from home. When Azerbaijan displaced her and thousands of other ethnic Armenians from their homeland of Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023, Lusine was forced to abandon her life in a matter of days.

A long-running dispute between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave has resulted in outbreaks of war and cross-border violence for decades. But this most recent escalation, since 2020, has been largely overlooked as international attention has been drawn to conflicts in Tigray, Myanmar, Ukraine, Sudan and Palestine. While Karabakh Armenians like Lusine have not given up on the possibility of return, the focus has shifted to building new lives in Armenia and navigating the challenges that come with it.

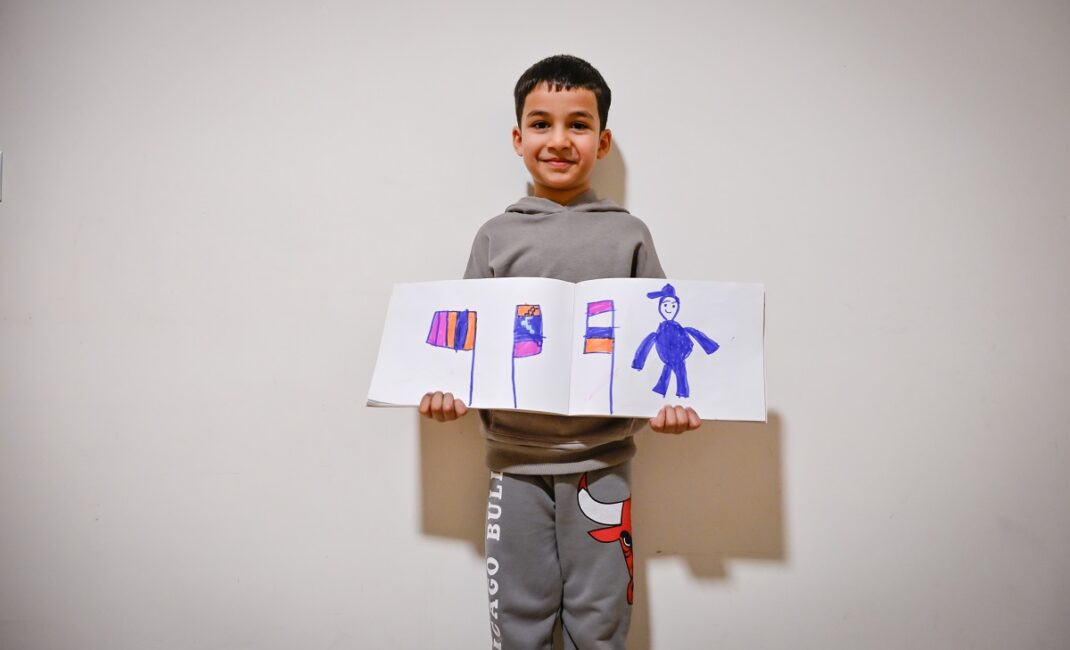

Artak Minasyan, left his home in Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023 with his mother and grandmother. Photograph by Emily Hanna.

What is the history of Nagorno-Karabakh or The Republic of Artsakh?

Established in 1923 by the Soviet Union as the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, the mountainous region in western Azerbaijan near the Armenian border, has been at the centre of hostilities between the two countries for over a century. Although located within Azerbaijani territory, the area has maintained a majority Armenian population – around 95% – for hundreds of years.

Before the latest conflict, ethnic tensions had been running high for decades. After the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991, the region declared itself an independent republic, leading to full-scale war (the First Nagorno-Karabakh War). Russian peacekeepers brokered a deal in 1994, which left the region de facto independent but heavily reliant on its economic, political and military ties with Armenia.

Intermittent clashes continued until war erupted a second time in 2020, known colloquially as the ’44-Day War’. After several failed attempts by the international community to negotiate peace, Russian mediators eventually forged a ceasefire deal and Azerbaijan claimed back most of the territory it had lost two decades before.

Lusine Minasyan with her son, Artak, who now live in Armenia, after fleeing their home. Photograph by Emily Hanna.

But violations of this ceasefire deal led to two days of fighting in September 2022, and subsequently, a devastating nine-month blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh by Azerbaijan, resulting in severe shortages of food, medicine and fuel. Azerbaijan launched a full-scale offensive against the region in September 2023, and quickly claimed full control. More than 100,000 ethnic Armenians, including Lusine, were forced to evacuate the region via the Lachin Corridor. Within just three months, the regional government was dissolved.

Why is no one talking about Nagorno-Karabakh?

The conflict and resulting exodus received minimal attention or condemnation at the time – and what little spotlight there was on the issue is fast shrinking. Armenia has accused Azerbaijan of ethnic cleansing. But Azerbaijan being chosen as the host country of the annual United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP) in November last year was seen as a flagrant dismissal by the international community of Armenia’s claims.

“We decided not to follow the news,” says Lusine. “I don’t expect anything to change. The international community is not bothered by what happened.”

Ashot Gabrielyan, a teacher who became a citizen journalist after the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict began. Photograph by Emily Hanna.

Lusine isn’t the only one that feels this way, and feelings of irrelevance on the international stage are not unfamiliar to Karabakh Armenians. Ashot Gabrielyan, a teacher who now lives in the Armenian capital Yerevan, became a citizen journalist in Nagorno-Karabakh during the nine-month blockade, which culminated in the forced displacement. He experienced the international neglect firsthand.

“I was keeping notes in my diary about the blockade,” Ashot says. “We felt transparent. We were there surviving, fighting for our lives, and no one noticed us.”

Born in Askeran, a small town in Nagorno-Karabakh, Ashot left for Armenia when he was 17 to study International Relations at the Yerevan State University. When the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War broke out in 2020, Ashot decided to return to Askeran. He remained in Nagorno-Karabakh until September 2023.

Azerbaijan closed the Lachin Corridor (a highway connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia) in December 2022, allowing only the International Committee of the Red Cross and Russian convoys to pass through.

“I decided to open up my life to the world and start showing what was happening here,” says Ashot. “I was sharing my daily life, the struggles of finding a single loaf of bread, or fruits or vegetables. Electricity would be out for almost 10 to 12 hours a day.” Ashot documented the struggle online, regularly posting images of the blockade alongside diary-entry updates on Instagram, where he has 6,000 followers.

Ashot and his parents and two brothers left Nagorno-Karabakh by car on 25 September. The journey to the Armenian border, which should have taken a couple of hours, took them two days. Satellite imagery collected by the European Space Imaging company, Marxar, captured the gridlock and endless stream of traffic crawling along the Lachin Corridor.

“It’s very hard to describe a situation where you have to stand in front of your whole life and pack your suitcase and leave,” says Ashot. Now, over a year on since his displacement, the reality is only just beginning to sink in.

“The real struggle begins when you start digesting what has happened to you,” he says. “It was only recently that we started realising, this is not temporary. We are here, we are displaced.”

How did the Armenian government and people respond to Nagorno-Karabakh?

The Armenian government has faced heavy criticism from Armenian civilians, both from the Republic and Nagorno-Karabakh, for its response to the exodus. Huge protests erupted in the capital Yerevan in the days and weeks that followed Azerbaijan’s offensive – and anger with the government has not yet fully subsided.

Peace negotiations in April last year, for instance, which resulted in Armenia making territorial concessions to Azerbaijan, sparked nationwide rallies, known as the ‘Tavush for the Homeland’ protests.

Led by political dissident Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan, the movement criticised the government for giving too much land away to Azerbaijan, compromising national security and not prioritising Karabakh Armenians’ right of return.

The arrival of 100,000 Karabakh refugees in Armenia – a country of only 3 million people – has inevitably put a huge strain on the resources and availability of affordable housing. While the Armenian government has rolled out various schemes to support the Karabakh refugees, including 50,000 dram per month (around £100) for each individual, the allowance is not nearly enough, Ashot explains. “It’s socially and economically very, very hard for [Karabakh] Armenians here,” he says.

The government announced in November that it would start rolling back the allowance in April to 40,000 dram per month, and to 30,000 dram by July. The eligibility criteria will also become more selective.

“When the stipend stops, there will be a lot of difficulties,” says Erik Baghdasaryan, who works at the Fund for Armenian Relief, (FAR). “Some have found jobs, others have property in Armenia already, but about a quarter are very dependent on this money.”

A new housing programme adopted in May 2024 aims to provide more options to Karabakh Armenians residing in subordinate living conditions or struggling to pay rent. Special certificates amounting to the value of 3 to 5 million dram (around £6,000 to £10,000) per person are now available to displaced Armenians – but the conditions are limiting. Refugees must hold citizenship of the Republic of Armenia to apply – but only a small fraction of the population do.

Following the government’s decision in October 2023 to effectively deprive Karabakh Armenians of their citizenship and instead grant them the status of ‘persons under temporary protections’, very few have re-applied for Armenian citizenship, partly out of fear of losing their right to return and partly because they already consider themselves Armenian (given they enjoyed all the rights of Armenians prior to this decision).

By the end of 2024, only 6,682 Karabakh Armenians had applied for citizenship, and 5,510 had obtained it - a very small fraction of the total refugee population.

Moreover, to be eligible to apply for the programme, you need to have two or more children, have lost your breadwinner or have a disabled family member; and have creditworthiness for obtaining a mortgage in order to purchase a property or plot of land. Larger funds are allocated to those settling in rural areas or border villages. The criteria will become more inclusive within a year, however.

“The acquisition of housing in the border regions is further complicated by the fact that most of the jobs in the country are concentrated in and around Yerevan,” writes political scientist Tigran Grigoryan in the IPS Journal, where he expresses skepticism about the longevity and effectiveness of the programme. “It is also quite obvious that the number of creditworthy people among refugees is limited,” he adds, pointing to the relatively low numbers of employment among Karabakh Armenians in the past year, with less than 19,000 of the 100,000 refugees employed.

Artak holding up his father’s medals. Photograph by Emily Hanna.

Added to this, Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh are finding their qualifications hold less weight than before and are struggling to adapt to a more competitive job market. Lusine moved to Armenia on 27 September 2023, with her son Artak and elderly mother, Silva. Her husband, who served in the military police, was killed in combat in 2020. She has been relying on his and her mother’s pension – and her administrative job at a construction firm in Yerevan – to support the family.

“It was hard finding a new job,” she says. “To work as a social worker here, you need to speak English – which I do not.” Lusine says the cost-of-living is becoming increasingly hard to cover. “My salary is not high and I’m the only one working. We try to sustain ourselves, but it’s hard.”

The emotional toll – how are Nagorno Karabakh refugees coping?

Various factors have impacted the mental health of Karabakh Armenians, not least, community breakdown. “It’s hard to stay in contact with people from Artsakh [Nagorno-Karabakh],” says Lusine. “My mum loves to talk on the phone, but I do it less often as I have more problems.” The older generation have been significantly affected by the displacement, as they previously relied on close family and friends for support.

“Now they are displaced, they have no one to look after them,” says Mira Antonyan, President of the Armenian Association of Social Workers. Around 18,000 elderly people were displaced in 2023, 600 of whom are waiting to be put in a home, Mira says.

Read more: Fleeing Palestine – and what happened next

The trauma of war and displacement, combined with mounting bureaucratic challenges, have left many in need of continued mental health support, a demand Armenia is struggling to meet.

“There is a special language you need to use when talking to displaced or extremely traumatised people,” says Ashot. “Armenia did not have any contingency plan.”

The country’s sudden humanitarian responsibilities led some experts to question the current system in place. “The methodologies need to be revised,” says Mira. “The approach should be proactive, they should find alternative ways of engaging people.”

While the government and NGOs have provided funding for psychosocial support programmes, the initiatives tend to be short-term and generic, rather than being tailored to the individual’s needs, Mira explains. Men, for instance, are frequently put off by the stigma surrounding therapeutic support and will be reluctant to ask for it. “We need to find inventive ways to engage men,” she says, “by introducing it into business or entrepreneurial programmes, for instance.” The need for longer-term and more specialised programmes of support for Karabakh Armenians – but those that balance the resources between locals and refugees fairly – is vital, she adds.

Ashot Gabrielyan, now works to support children from Nagorno-Karabakh. Photograph by Emily Hanna.

Children have suffered significantly – both in terms of education and psychological development. Around 30,000 children were displaced during the war according to Armenia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs. Ashot, who now works as a teacher supporting children from Nagorno-Karabakh, has witnessed the difficulties they are facing firsthand.

“When we started the needs assessment, we found that 87% of the children had serious trauma, after the war and displacement,” he says. “One child lost the ability to speak. We have cases where kids are isolated from everyone. They don’t want to integrate and they suffer from severe sadness.” Ashot and his organisation, Teach for Armenia, support the children through activities and catch-up classes. However, the organisation relies on private funds and has a limited capacity, meaning there are likely children falling under the radar.

Refugee initiatives – the power of art therapy

Hasmik Arzanyan, single mother who started ‘Sand Planet’ in Yerevan. Photograph by Emily Hanna.

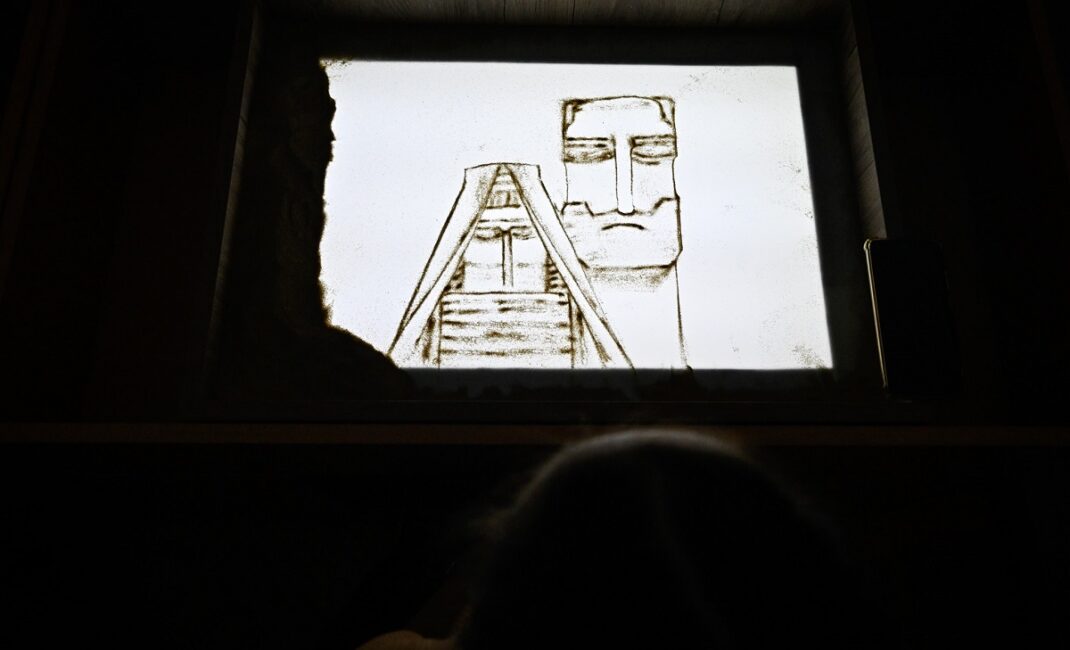

Hasmik Arzanyan, a single mother of two, artist and refugee from Nagorno-Karabakh who works in human resources, has found a creative way to support these children. Following the 44-day war in 2022, Hasmik started her small craft therapy group, ‘Sand Planet’, inviting children to come and draw fairytale figures in the sand on up-lit screens.

“It was a fantastic place, where kids would come and draw with classical music on in the background,” says Hasmik. After the displacement, Hasmik found a studio in Yerevan where she started hosting the classes again, inviting children from Nagorno-Karabakh to attend every couple of weeks.

Making sand art in Hasmik Arzanyan’s craft therapy group for children ‘Sand Planet’. Photograph by Emily Hanna.

Like Lusine, Hasmik is also a widow. Her husband was killed in a fuel depot explosion near Stepanakert during Azerbaijan’s military offensive, a tragedy which left over 170 people dead. News of his death arrived via an ambiguous message from one of her husband’s friends.

“They asked me to send a picture of his cross, I didn’t understand it was for identification until later,” says Hasmik. “I was in shock – for a long time I couldn’t even express my feelings.” The family fled Nagorno-Karabakh on 25 September. “In one day, I lost everything – my house, my business, my car, my husband.”

While Hasmik’s economic situation is stable – and she has not entirely lost contact with her community – the toll on her mental health has been significant. “Here, I have this feeling that we live as if it were our responsibility,” she says. “In Nagorno-Karabakh, we enjoyed life. But here, we just live, we just breathe. A lot of people have this feeling.”

Hasmik Arzanyan’s ‘Sand Planet’ group promotes relaxation through art. Photograph by Emily Hanna.

The craft therapy initiative allows both Hasmik and the children to live in the present moment, to relax and to connect with their senses. “The art helps me, it relaxes me,” she says. “When the lights are off, when I’m drawing in the sand and just see the light on the table, I travel to another world: the world of art, and of relaxation.” She hopes one day to open her own centre. “It will be the best centre in the world!” she says. “It will be new and unique.”

What does the future hold for Karabakh Armenians?

Multiple legal precedents have affirmed Karabakh Armenians’ right of return. This includes the International Court of Justice’s ruling in November 2023. Both Armenia and Azerbaijan brought anti-discrimination claims against one another under the CERD (Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination) and the court also issued emergency measures to ensure the safe return of ethnic Armenians to Nagorno-Karabakh. But while the order is binding, it is not enforceable. Additionally, the Swiss parliament adopted a resolution in December 2024 to establish dialogue between representatives of Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan and facilitate the return of refugees.

However, while there has been some progress at an international level, more locally, negotiations lack the momentum and conviction needed to bring about real change. Vartan Oskanian, Armenia’s former foreign minister (1998-2008), published an op-ed in November last year, criticising the country’s “troubling silence” over the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh and arguing that the Armenian government is the “primary obstacle” to the refugees’ return.

There have been reports of Azerbaijani troops destroying both residential buildings and sites of Armenian cultural heritage in the region. From 1997 to 2011, the Caucasus Heritage Watch documented Azerbaijan’s destruction of the Armenian Old Jugha Cemetery in Nakhchivan (an autonomous region controlled by Azerbaijan but with a deep history of Armenian presence).

The organisation fears that what happened in Nakhchivan sets a dangerous precedent for the future treatment of cultural landmarks in Nagorno-Karabakh. As the memory of those who lived there before is quietly eroded, it begs the question, what exactly would the refugees be returning to?

Sand art of the ‘We Are Our Mountains’ sculpture in Nagorno-Karabakh. Photograph by Emily Hanna.

While life now might be difficult and the future remains uncertain, Karabakh Armenians have not given up on their hopes of return. “Working with the future generation, that is the one thing that gives me hope,” says Ashot. “While I’m a young person myself, I feel our generation is not going back [to Nagorno-Karabakh]. I don’t want to push the responsibility, but I believe it will be my students who return.”

All photography by Emily Hanna.

Read more: