This evocative story brings to life the challenges – and rewards – of teaching during the Covid pandemic lockdown. Ruby Turok-Squire won the postgraduate prize in Lacuna’s 2020 Warwick Law School Writing Competition for detailing her experience of cycling from garden to garden to read with refugee children under the restrictions of social distancing in the West Midlands, UK.

This story is based on real people and events. All names have been changed.

“I don’t know what they’ve seen.” Hilary said it so quietly, almost as if it was unimportant.

She was about to introduce me to two young boys from Syria who had come to England with their parents several years ago. They had been out of school since lockdown began in March. Now it was June.

They hadn’t been considered vulnerable enough to stay in school during lockdown. Despite not having books at home. Despite the fact that their parents didn’t speak much English and had hardly been to school themselves.

“I wouldn’t be worried if it was their first year here,” Hilary murmured. “But it’s been too long.”

We were walking down a little alleyway behind a row of large, new council houses, watching the washing floating in the back gardens, sidestepping a stray cat, counting the doors in the fence.

“One of their teachers told me that Abdul can’t even read the word ‘I’.”

Hilary worked for a charity supporting refugees in our town, and through my work for the council, I had heard they needed help. We made a plan.

Each Saturday, I would cycle round to Abdul and Khalil’s house and set up a mini classroom in one corner of their back garden.

We would play mathematics games, read through picture-books – whatever would help them to concentrate. Then I would cycle on to the next family of refugees, going from garden-to-garden, teaching the older children and whichever younger siblings wanted to join in.

This was day one, house one.

Read more: Hungry in the school holidays: Are voluntary schemes the long-term answer?

We pushed open the final door in the fence. Once the cloud of greetings had passed and Hilary had gone inside with their parents, I started to see a little more of my new students.

Khalil had a way of looking down even when he was looking straight at me.

He cleaned what was to be my chair of last night’s rain and mud. I reminded him to clean his own chair too.

Abdul’s eyes were all over the place, as if looking for distractions before they occurred.

Their smiles were wide, uninhibited, but their missing teeth were a reminder of what they had endured – when there was no food in the refugee camps except for sugary snacks, the family ate what they could.

Hadi, their youngest brother – he would have been wrapped in his mother’s arms for most of their journey to England – wandered about their garden with his hands outstretched, welcoming the unknown wherever he found it.

His elder brothers’ eyes looked much narrower to me. As if guarding themselves against what they might see, before they saw it.

Read more: GCSEs: Are major changes to school exams damaging children’s health?

“Let’s try this book,” I suggested, pulling out a random book from the collection Hilary had lent me. “I know that one!” Khalil said. And he often did know, it turned out.

His reading was good, but the problem was that Abdul could hide behind his brother’s abilities. I thought I could feel it coming, the wave of fear that seemed to paralyse Abdul from time to time.

“Why don’t you want to read any more?”

“Because I’m no good at it.”

“You’re an excellent reader! And you’ll improve. It takes time.” I would try to melt the sudden iron in him.

“You might even enjoy it. Look! Doesn’t this look interesting?” I would point to a picture. He liked pictures. He could read pictures. And he could read them in so many different ways.

“Why don’t they do this instead?” he would ask, pointing to one of the characters.

“What would you like them to do?” I would ask in response, and we would find a way to keep reading together.

Each week, Abdul and Khalil turned up on time to class in their back garden, cleaned the rainwater from our chairs, and set out into a book with me.

Read more: Teaching about ‘Creative Expressions of Resistance’ in contemporary Cairo

“What’s this word?” I asked Abdul once, and after a pause just long enough for a teacher of a class of thirty students to give up on him and move on to the next child, he answered, “I.” Confidently, loudly.

Of course he could read the word “I”. Getting him to tell me that he could was the real challenge.

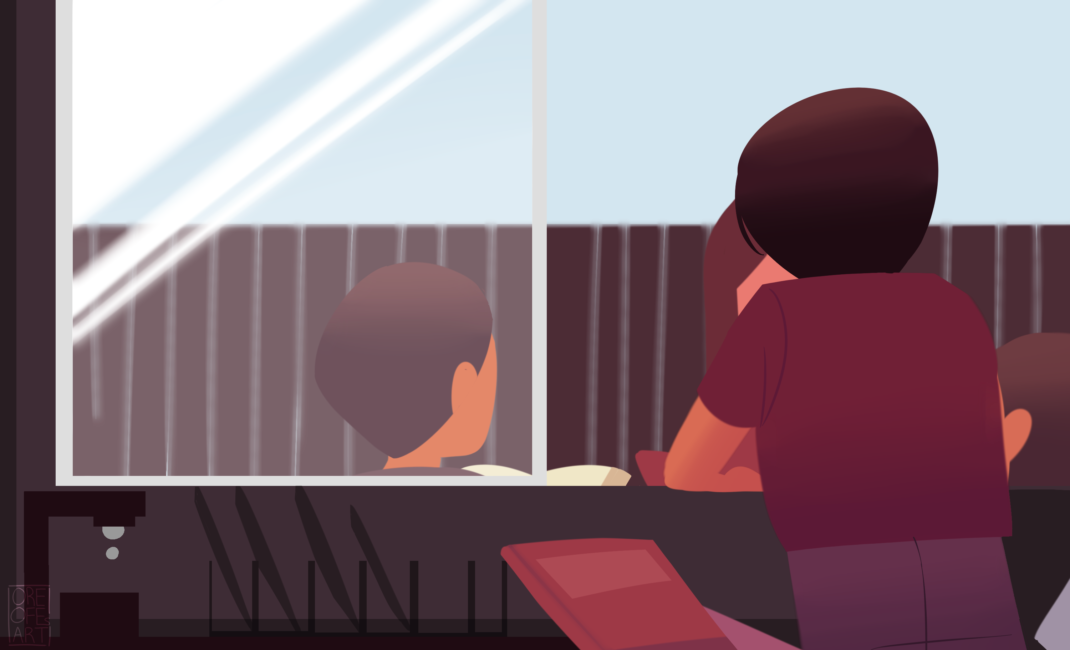

I remember one day when, halfway through a book, Hadi – he can’t have been older than three – leant out of the kitchen window behind us and started reading along with us, making whatever sounds we made, nodding when I encouraged him.

“Yes,” he would say, agreeing upon whichever word his brothers had said that one was. And then, at an always miraculous, unpredictable moment, a whole word would be born out of Hadi’s mouth.

I would point and ask, “what’s that word?” and before his brothers, all on his own, we would hear him say, “dance,” and wonder how on earth he suddenly knew what the letters made.

In such moments, for me at least, the present overtook the past, with all of its difficulties, and, for a while, drowned them completely.

All images by Oreofe Morakinyo.

More stories from our 2020 writing competition:

- Move! A Rohingya child dances for hope in the world’s largest refugee camp

- Fleeing Palestine – and what happened next

- Reopening old wounds: The never-ending tale of police brutality in Kenya

Read more: