This piece of creative fiction about Bloody Sunday, originally written as a response to one of the themes of the Writing Human Rights module at the University of Warwick, explores a historic event which continues to impact the Catholic community in Northern Ireland. The story was inspired by the words of 17-year-old Jackie Duddy’s sister, Kay: “We didn’t just lose a wee brother, we lost a generation”.

I’m not in from school five minutes before Mammy, in a fit of rage or sadness – I couldn’t quite say what – asks me to go and get a loaf from Mr Tooley’s. I stopped taking sandwiches for lunch three days ago, but due to some sort of agreement she had with her herself, Mammy had persevered with carving the mould off.

Now, it seems, she had broken her resolve on two things, not buying bread, and not talking to her daughter.

It’s bleak today, same as every day, and the air seems thick with smog or dirt or whatever was most recently burnt. I walk down the street, a row of twenty terrace houses on either side. Crumbling in places, the landscape changing from what was once a sandy bricked empire, to one that would fall down entirely if the wind blew too strongly.

Cormac, from two doors down, skulks out into the road with a boy from the next street over.

They used to move about in a pack of five, each lad without a pick on him, but all feigning intimidation, nonetheless. But, in August, the brother of one of the boys was shot dead as part of Operation Demetrius, and his Ma couldn’t bear the vegetable stew that the neighbours would bring by.

The other two families fled shortly after. Only two, then, were stupid, or hopeful, enough to stay.

“How’s your da?” I call over to Cormac. “I heard he got caught up with the army at Saturday’s march.”

“Bloody and bruised,” he says back, “The Green Jackets did a job on him sure, beat him half to death. Rubber bullets and tear gas for the rest of us. Da calls ‘em sadists.”

When we were six, I thought I might have married Cormac, with his round cheeks and bright eyes. A decade later and his clothes hang off his jagged frame. His jumper, with sleeves too long, has holes by the cuffs that he puts his thumbs through. Cormac’s cheeks are hollow now, and while his eyes are still bright, it’s with something far more cynical than youthful fascination.

“Sadists alright.” I say, as a piece of discarded paper flutters along the pavement, charred at the corners.

Cormac’s mate picks it up, crumples it into a ball, and kicks it.

***

I take the long route to Mr Tooley’s, along the path by the River Foyle, the border between our land and the Waterside, where the Protestants live. The sky is grey over on their side too, though their houses don’t crumble like ours.

Mr Tooley’s street is quiet, except for the distant murmuring of a radio, and the sound of my shoes hitting the road. A bicycle lies, collapsed on its side, abandoned outside the shop with no sign of its owner, the front wheel spinning imperceptibly. I enter with a ring of the bell.

“Well, hello there Bríd, now I haven’t seen you in a while.” Mr Tooley glances up at me, over the edge of his oval spectacles, as he sits behind his wooden counter. “What are you needing?”

“Just bread, Mr Tooley. I’ll go on ahead and get it myself.” I reply. He smiles, nods, and returns to his open newspaper.

It has just turned 4pm, and Barleycorn’s ‘The Men Behind the Wire’ is swiftly replaced by a sombre voice. I begin examining the back shelves of Mr Tooley’s shop with forensic precision.

“My dear, if I turn it up, will you give those shelves a break? If you look too closely, I fear you’ll find woodworm.” Mr Tooley says, eyes still glued to the paper in front of him as he reaches to turn the dial on the radio.

I sigh at my apparent lack of subtlety, mutter a sheepish “thanks”, and move back over to the countertop, perching myself on the end of it.

“The prime minister, Brian Faulkner, has warned against the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association’s planned protest ahead of this Sunday, the 30th of January, reminding the public of the ban placed against all parades and marches until the end of this year.”

The cautious swinging of my legs forms a toneless thudding against the chestnut wood of Mr Tooley’s counter. Thump. Thump. Thump. The news reporter speaks with the same monotony.

“The NICRA has responded, saying they are placing a ‘special emphasis on the necessity for a peaceful incident-free day’, in answer to the violence which broke out at last Saturday’s anti-internment march at Magilligan strand. Frank Lagan, Chief Superintendent of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, reports to have been in contact with the event’s organisers –”

“Thinking of marching, are you?” Mr Tooley, having heard enough, turns the radio back down. He looks up from his newspaper, and towards me.

“I’m afraid so, Mr Tooley.” I reply. I stop my swinging legs, and look down at patent peeling off the toe of my right shoe.

“Bríd,” He sighs, placing his newspaper aside.

“I was younger than you when the Easter Rising happened, but I remember the feeling. The belief that one act would change the order of things, that we were on the verge of a breakthrough.

“I held onto that belief so tightly that I lost sight of everything else, for a while. But what I realised was, after the dust settles things never really change.”

The notion of Mr Tooley being any age other than ‘old’ is one which I can scarcely fathom. He’s been ‘old’ for as long as I’ve been alive, his light dusting of white hair one feature I’ve always remembered him by. That, and his innate ability to make a person feel microscopic, all the while maintaining a level voice and kind eyes.

This time, however, his soft tone feels unbearably similar to that used to coax a toddler out of a tantrum, and something within me snaps. I move off the countertop and straighten my back.

“And we should just accept that?” I say, my voice as stern as I can muster. “We should accept that our surnames could land us in prison, that being Catholic is a death sentence? That our government agrees to policies against our people? Should we accept that the British army has free rein to beat us and gas us and shoot us?”

“A war won’t help matters.” Mr Tooley sighs, the harshness of his crow’s feet seeming suddenly misplaced within the frailty of his face.

“We don’t want war, Mr Tooley. We want peace,” I soften my voice. “And the only way we’ll get peace is if we show them that we’re deserving of rights just the same as them. We have to show them because it’s the only way they’ll ever see.”

“I know you won’t listen to me Bríd, Lord knows I wouldn’t have listened to me, so the only other thing I’ll say is this: be careful.”

There’s an emphasis placed on the last two words, which Mr Tooley doesn’t address.

Instead, his expression regains neutrality, as he picks his newspaper back up. I put some coins on the countertop, grab a loaf and leave, envious of Mr Tooley’s ability to end a conversation, and disappointed in myself for letting him.

***

Over the next few days, Mammy fully neglects her vow of silence in an attempt to explore more persuasive methods. These methods usually take place over breakfast, typically with support.

On Thursday, Geraldine from the house opposite comes round – an unusual sight for 7:30am – to discuss how her niece has heard a soldier say he’d be “taking care” of protesters on Sunday.

Friday, and Connie from down the street is drinking tea in the kitchen when I walk in, in my pyjamas. She tells Mammy that her cousin in the Constabulary has warned against her going to the march, but won’t elaborate when I ask her for his reasoning.

By Saturday, I decide not to leave my room, so long as we have company.

Now, on Sunday, I stand in the hallway, fingers fumbling my laces, adrenaline pumping through my body.

“You’re still going then?”, Mammy says, emerging from the lounge with red eyes. “There’s really nothing I can say that will keep you here?”

“No, Mammy. I have to go.” I reply, hoping in some way she’ll be proud of my persistence.

Mammy kneels down opposite me. She moves my shaking hands aside, and double knots my laces. Afterwards, she kisses me on the cheek, her face wet.

“I’ll be back in time for dinner.” I say.

The Creggan Estate – the march’s starting point – is barely visible for the masses occupying it. The sound of thousands of feet fills the street as we begin the walk towards Bogside, moving in half speed, each step taken in slow motion as bodies are pressed against bodies.

We move as one being, a flood packed into the streets of Derry, following the motion of the tide. Forward-forward-back. Forward-forward-back.

The air is biting, and frozen fingers interlock with those of people we’ve not yet met. The army has already begun cordoning off roads and paths in an attempt to restrict our movement, to limit our momentum.

In response, the group guiding us starts chanting ‘We Shall Overcome’. It’s gentle, but determined, the murmuring of lapping water. Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe, we shall live in peace someday. Two of them carry a banner, a blue flag with “Civil Rights Association” written on it in white font.

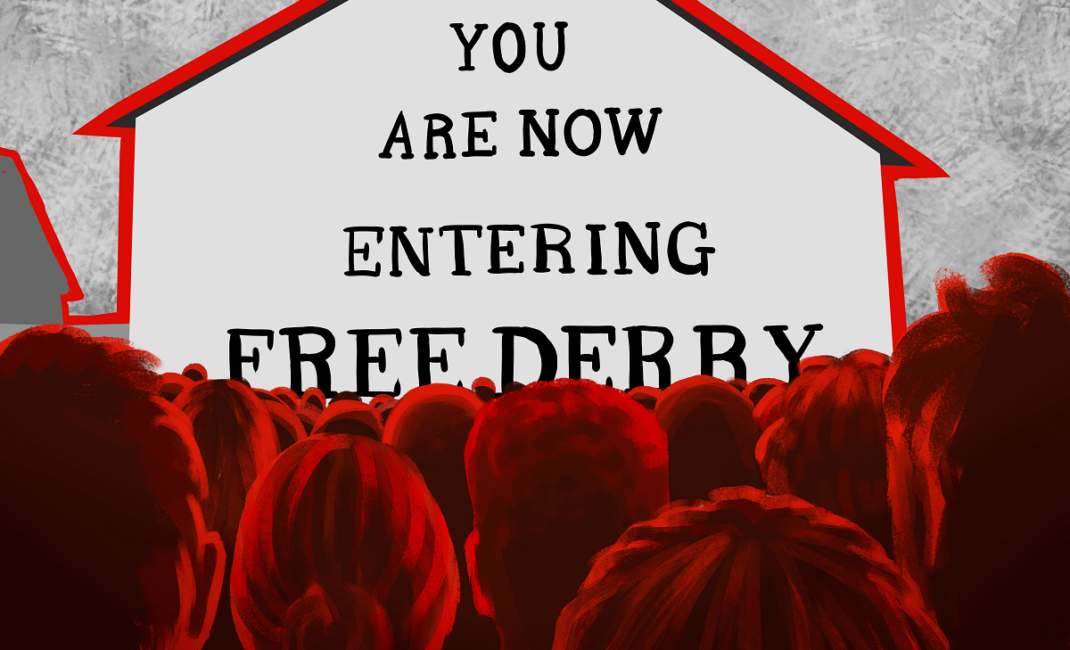

We reach Free Derry Corner, ‘YOU ARE NOW ENTERING FREE DERRY’, printed on an end of terrace.

Each letter is a metre high, bold in black against the whitewash wall, watching over the street below. A sign of freedom, restricted to bricks and mortar, but not extended to the lives that inhabit them.

The flood splinters: half the group stills, rooted to the wall, the other half continues on. I follow, swept up by the tide. Straight on, forward-forward-back. Turn right, forward-forward-back. I’m carried to the front of the flood as we push down William Street.

There they wait, with reinforced exoskeletons and guns strapped to their spines.

Death camouflaged in shades of green and brown. Watching, waiting, anticipating our next move.

Yet, regardless of what move we make, theirs is already decided. I try to sink back into the crowd, but the flood stands still, fifteen feet from the barricade.

A rock arches over my head, through the sky towards them, a wave tipping over a wall. Before it has the chance to hit, however, our breath is caught in our throats as pressured water chokes and blinds us. The water subsides, and the flood surges forward whilst I stand spluttering. The people are met with batons and rubber bullets.

Then, out of the air, cutting through the shouting and pleading, like a butcher’s knife through flesh, I hear it.

Gunfire.

This isn’t the sound of rubber bullets, these are the ones that kill.

Quick, piercing, severe, from somewhere out of sight.

One.

I try to run, but my feet cling to the ground beneath them. I try to scream, but only hollowness rises to meet me.

Two.

The sound of artillery fills my head from one direction, the anguish of broken bones from the other.

Three.

I fall to the ground, knees balled to my chest, arms over my head.

Four.

I want my Mammy.

Five.

It stops.

Five short rounds, over in a heartbeat, or hours, I’m not sure. Blood rushes to my ears. Bodies rush by, without a destination, some towards the riot, some towards the gunfire, some round in circles just to keep moving. Others, like me, are drowning in the crowd, grappling for leverage or a lifeline, submerged by the tide.

Between panicked legs I see a boy, younger than me, lying on his back. His face is distorted in pain, his trousers turning maroon as his leg forms a right angle to his body. To his left, an older man is sat, clutching his arm as blood leaks through his fingers.

The riot breaks up as the tide is forced back by white gas. On unsteady legs, I join it as it retreats down Rossville Street, back towards Free Derry Corner. I propel myself forward, my footsteps matching the urgency of my pulse.

I reach the Rossville Flats, great slabs of concrete looming over Bogside like a grey toned watch tower. Stony faced and unsympathetic.

“Go back!” I hear from far ahead. A single voice, and then a screaming chorus. “Go-”

Gunfire cuts through the air again, but this time I can’t count the rounds.

My legs surge forward with subconscious necessity, into the courtyard of the flats, the sound of death following me no matter the direction I take.

Bodies, who once joined together, now lie apart. Some are being carried to safety, some are already cold. Some still have their fingers interlocked.

Seeking some form, any form, of shelter, I crawl under the nearest car and close my eyes, my face sinking into the cold ground.

I put my hand over my mouth, fearful to make a sound, as if in silencing myself I may disappear completely. I count in my head to focus on something besides the crying and the artillery. At 1,392, the gunfire stops.

“The Army returned the fire directed at them…”

His expression is colourless, TV static blurring the edges of his face. He speaks without inflection, black holes in his skull, scanning the teleprompter for his next line. My eyes are level with his, like looking down the barrel of a gun.

“…And inflicted a number of casualties on those who were attacking them, with firearms and bombs”.

Monotone. Numb. Flashes of film shoot by, pixels arranging and rearranging, people protesting for peace, soldiers ready for war. Flags and tear gas and water cannons. Gunfire and guiltless murder. I search for the fact in fiction. Stones met with bullets.

My eyes look forward unblinking, but where the news reader once met my gaze, I now look at a dark screen. At some point Mammy must have walked in, turned on the lamp and turned off the box.

“Bríd, pet, you’re not going into school today.”

I look down at my uniformed lap. I don’t remember putting it on, but then again, I don’t remember waking up or going to sleep. I want to scream but I can’t. Screaming is meaningless when gunfire is louder.

A priest waves a blood-stained white handkerchief. A boy, sprawled limply across four sets of arms.

All artwork by Ellie Stocker.

Read more: