Discovering her great grandfather’s sketches of the Second World War, Camille Aymond recounts his story of being held by the Nazis in the Rawa-Ruska German war camp in Ukraine.

This piece of creative non-fiction was originally written as a response to one of the themes of the Writing Human Rights module at the University of Warwick. The module confronts human rights themes and develops creative responses to them in writing. Students have free rein to choose the topic and style of their stories. They create journalism, short fictional stories, sci-fi, screenplays, comment pieces, podcast episodes and TED talks. We have worked with students to develop the best examples of their writing and publish them on Lacuna (find more here). Camille Aymond’s story, a response to the War Crimes section of the module, is based on the experience of her great grandfather, Pierre, and the pictures he drew to document the Second World War. Learning about Pierre’s real-life experiences in the Rawa-Ruska camp, Camille based her story around her great grandfather’s sketches. She set the surrounding story in Pierre’s hometown using fictional elements to introduce the discovery of the images and Pierre’s story. Camille is a law graduate on the LLB who is going on to pursue a master’s degree in human rights.

The house had never been so quiet. My father was slowly packing all his aunt’s trinkets in brown boxes, letting the grief fill his eyes. Monique had died a week ago and my dad and I volunteered to travel to Mosnes, a small village in the Loire Valley, to take care of her house.

“Do you mind checking the attic?” my father asked, “I believe there are few unopened boxes, maybe you’ll find some hidden treasures to cheer you up.”

I smiled and nodded as I climbed upstairs and lowered the rusty ladder. Once in the attic, I took a look around.

Some mouldy boxes in the corner, spider webs lazily hanging from the wooden beams, a ray of sun from the skylight illuminating the dust.

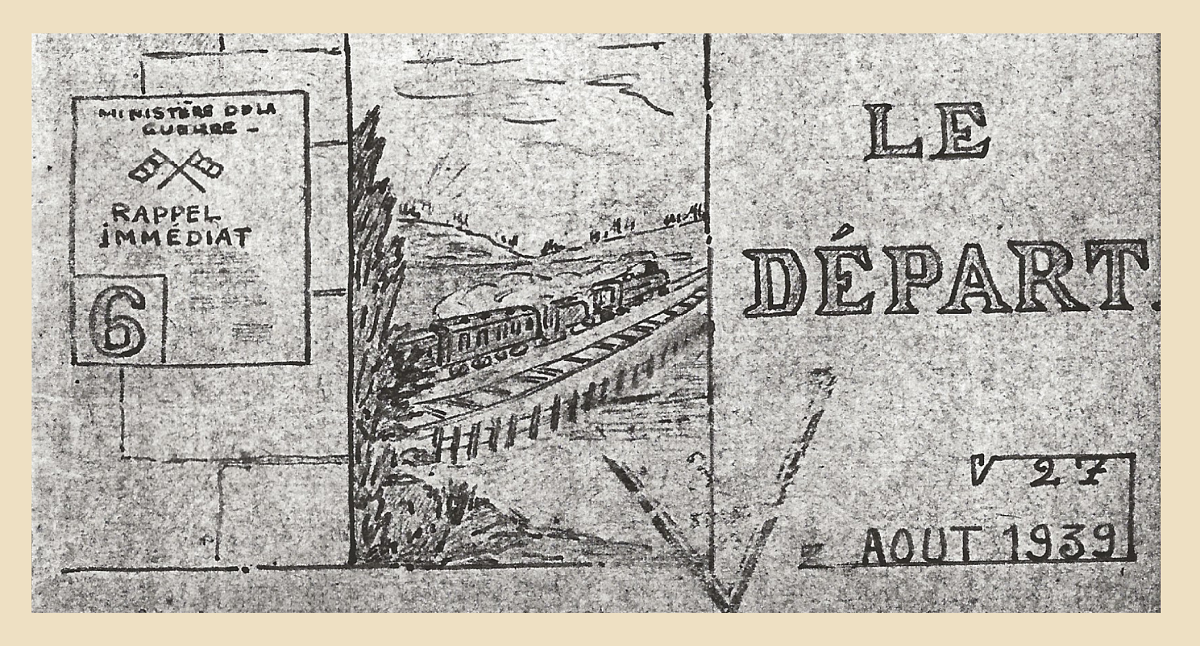

I spotted a couple of metal boxes hidden under some postcards and a few books. Grabbing a few yellow pages filled with drawings, on the front page, in cursive handwriting, I read: “June 1940, the Departure.”

Beneath the title was a drawing of a train alongside another sketch of a poster announcing to the French population that all men and boys over 18 years were mandated to join the fight. The train was seen leaving, a few clouds scribbled with a dark pencil. My eyes wandered and I noticed a small inscription at the bottom right of the page: “Pierre Aymond”.

“What do you have here?”

I flinched, suddenly aware of the dust covering the floor of my great aunt’s attic. My father was standing at the entrance.

“I’m not sure,” I answered, “there are a bunch of old drawings marked around 1940.”

Read more: Nuremberg: A Tale of Memory and Forgetting

He sat down next to me and silently took from my hands the picture of the train. He smiled and said: “Those drawings were made by my grandfather, Pierre, but I knew him as ‘pépère’. He was a kind man, he used to let me sit in the back of the truck with my sister. He’d take us on drives along the dirt roads around the village so we could play, sometimes going faster and turning the truck so we would feel like we were flying.”

He paused and took another look at it.

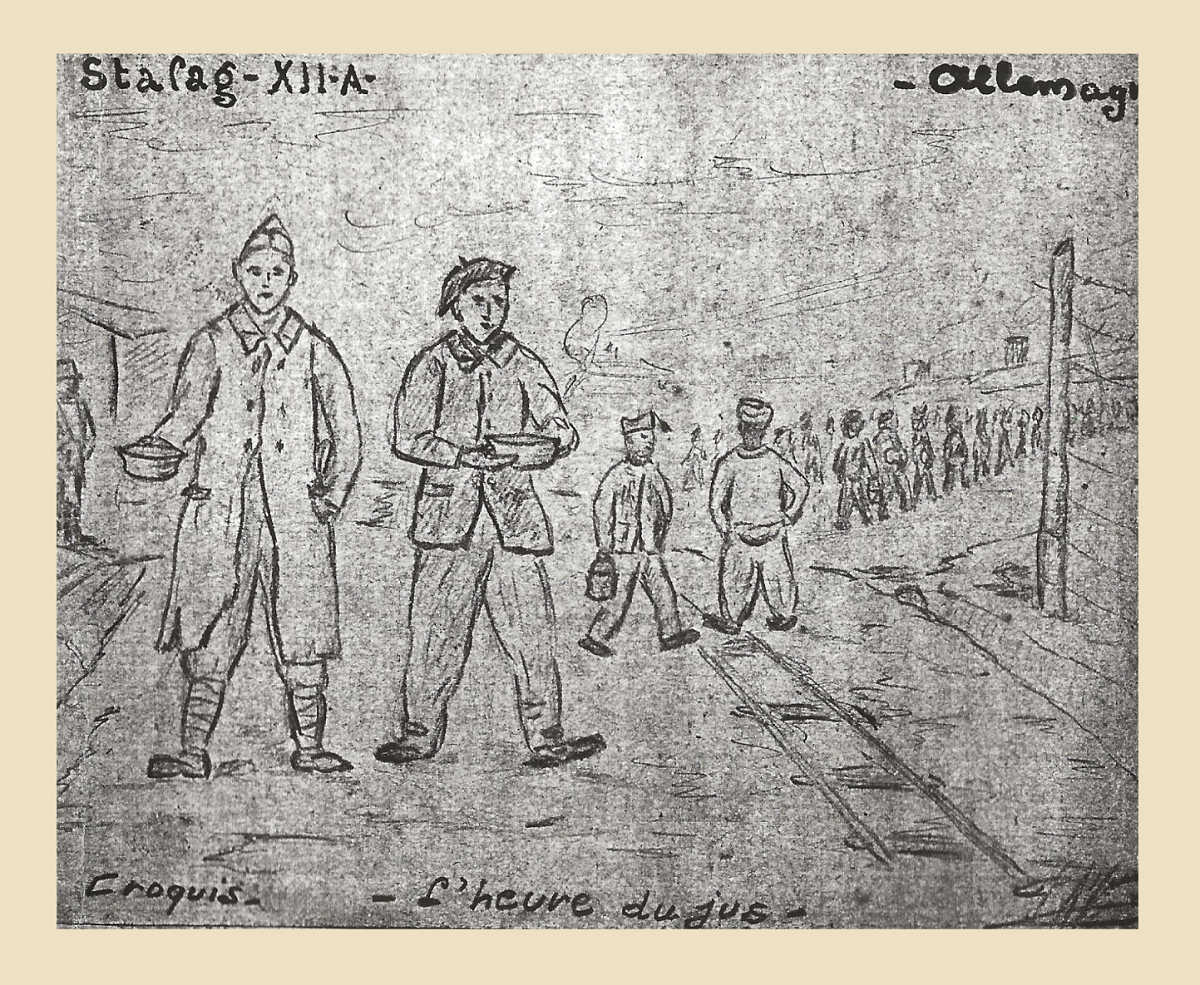

On the bottom right was another inscription: “Stalag XII A – Germany.” Under it, a couple of soldiers in grey were holding a bowl. They were both in military uniforms. In the back, an endless line formed by other detainees, queuing for something. Barbed wires were forcing them to stay in a straight, disciplined line.

It was followed by a drawing of a man smoking a pipe alone. With the lack of colour and the shading of his cheeks, he seemed to be carrying the fatigue and fear of an entire lifetime, the kind of fear that not even tobacco could take away.

“You see,” Dad said, “Pierre was called to war when it first started. During World War II, unlike World War I, the fights in the trenches were short. After Pétain capitulated, my grandfather was made a prisoner of war in Germany as you can see from the drawings. He was a recidivist – a dissident. That means that he disobeyed the Nazi officers’ orders and tried to escape. The Nazis considered him to be undisciplined, unable to be moulded into a prisoner meeting their criteria for what they called ‘rehabilitation’.”

He fumbled around in the case to pull out a few more drawings. He handed me a sketch depicting what appeared to be wooden barracks. One of them had the door open and you could see hay on the floor. Next to this was a picture of two soldiers, their faces blurred by the same pencil used for the landscape.

In April 1942, the camp of Rawa-Ruska, formerly for soviet prisoners, was used for disobedient French soldiers. Pierre was sent to the camp, in western Ukraine near the border with Poland. After the Wannsee Conference, it was decided that any recidivist was to lose their prisoner of war status. The conditions at Rawa-Ruska were rough, and it earned the nickname “camp of the water drop” because there was one solitary tap to provide water for water the whole camp. About 2,000 French war prisoners were deported there, to “Vernichtungslager 325” (or “extermination camp 325”).

I took another drawing showing a room divided in two by a path constructed from wooden planks. Some tools were left against the walls. A couple of shovels, a few buckets.

Pierre was drawing the tools and the tasks and the building he was forced to work in, putting concrete on top of the muddy, frozen floors.

Behind this, Pierre drew two prisoners playing cards on the floor. They were surrounded with one or two pots. They looked like they were used to cook the soup given to the detainees once a day. One of the men was smoking, sending out a grey cloud from the tip of the cigarette.

I compared it with the picture I had seen before, the one with the prisoners holding the bowl of what I guessed to be containing soup. Working in the kitchen, I imagined, must have been more comfortable than having to queue for food in the cold.

But the drawings, as clear and monotone as they may be, don’t come close to describing the cruel reality.

Dad said: “The camp of Rawa-Ruska was composed of four barracks without any doors or windows. They hadn’t managed to finish the construction of those, allowing in a cold so raw that it settled inside the bones of every detainee. Bear in mind that in winter, the temperature fell between -20°C and -30°C. I remember Pépère told me once that they had to stand outside for two hours in the middle of the night while the camp officers searched their barracks.”

He paused, eyes travelling along a piece of paper. I grabbed a couple more, trying to display them on the floor in a vague timeline. I was trying to understand Pierre’s story accurately, avidly going through the drawings, hoping to find a black scribbling or a footnote – any precious potential clue. On one of them, I read “coste 304 – Night of 13 to 14”. I sighed. No year.

“It’s probably around May or June 1940,” said dad, reading my mind. “The drawing above it is a combat fight.”

Dad traced his fingers on the left part of the picture where about seven or eight soldiers were carrying some type of rifle. They seemed to be running towards a lighthouse, leaving the barbed wires and the dry bushes behind.

Below there was another drawing. This time, the bushes and metal wires were forming a precarious wall in front of two soldiers. Both were looking through their rifles, aiming at the other side. Four bags were separating them and the soldier on the right had one attached to the belt of his gear. A plane was flying in the sky but neither of them seemed to notice it.

“It’s like a jigsaw puzzle,” my dad said before falling silent, searching for clues hidden in his memory.

“How did this ended-up here?” I asked.

“I think everyone in the family received a copy of it but the original pages were distributed to his children.”

We kept looking. I pulled one page out and put it next to the pictures of the warfront. These two drawings were what we believed to be Pierre’s memories of his last combat.

The first showed a soldier, crouched inside a small cave. Outside, a shovel and a rifle were laying side-by-side in the mud. His backpack was undone, close to the entrance. With his knees up and his hands around his ankles, he looked like a little boy hiding in a tree house. The ground was chaotic, a few leafless plants scattered around, mixed with the dirt and rocks.

This second picture also showed a soldier but this time, he was hiding behind a tree, his hands on his rifle. He was protecting himself from an explosion. It appeared that the impact was throwing out metal pieces in all directions.

“Shortly after that,” dad said, “Pierre was captured and sent to a prison camp in France and then another in Germany. He tried to escape, so the Nazis sent him to Rawa-Ruska.”

“So before he was sent to Rawa-Ruska, he escaped from a camp in France?” I asked.

“Not exactly. See, after France capitulated, he was sent to Germany to work in a camp with his fellow inmate and friend Louis. They decided to escape after their shifts, once everything went dark. They nailed pieces of rubber to the soles of their shoes. They walked for hours with just a few sugar cubes hidden in their pockets.”

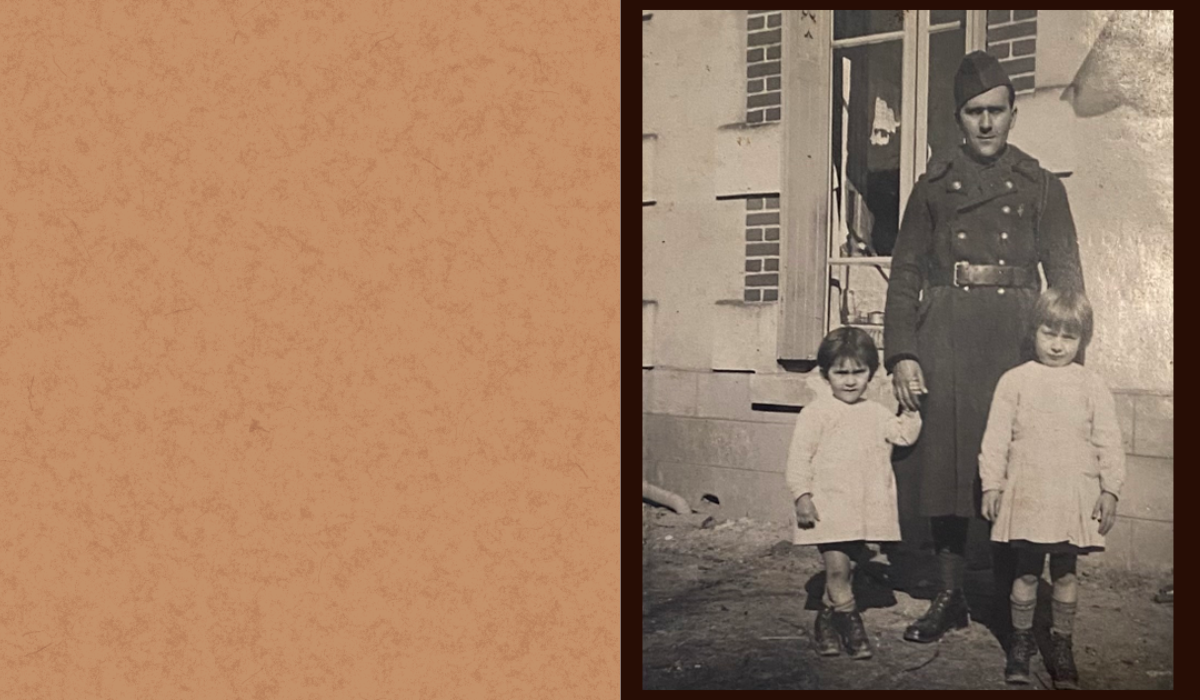

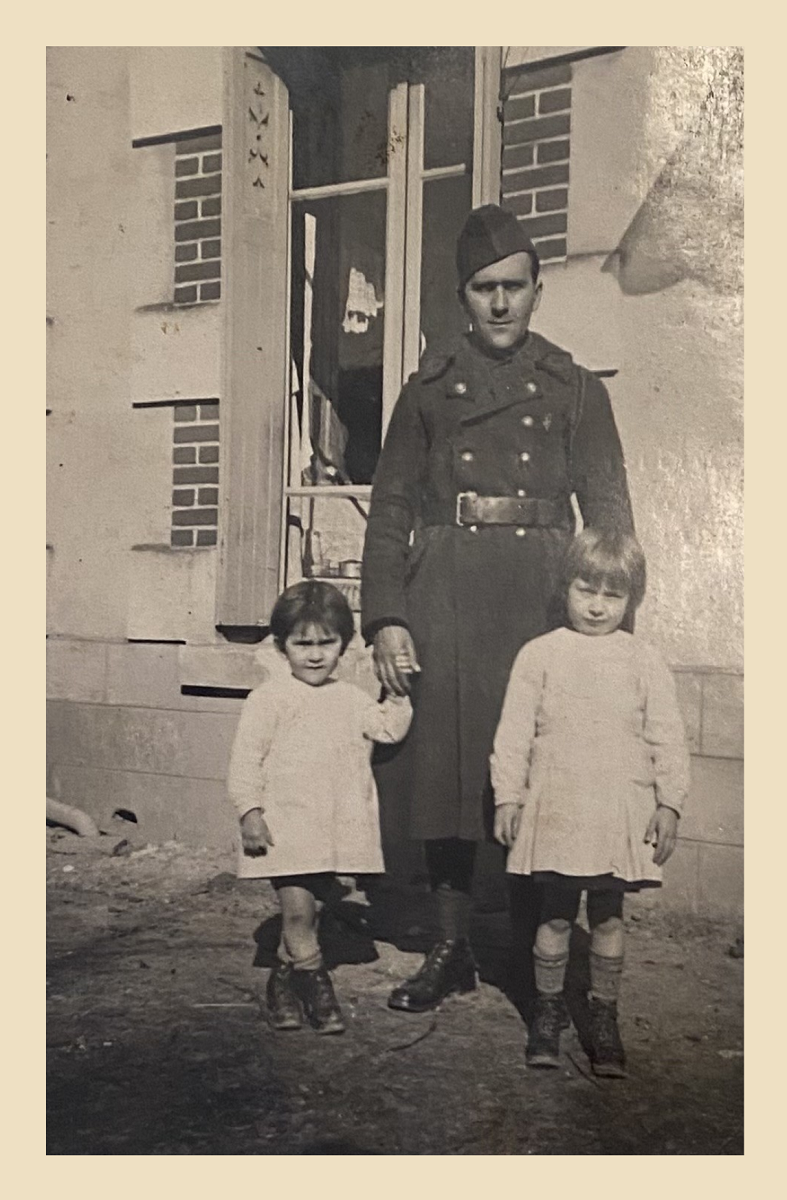

My father handed me a picture of a soldier in uniform. He was standing behind two little girls, wearing similar dresses and some high socks.

“The man in the photo is Pierre and those are his first two daughters, my aunts. On the left, you can see Micheline and next to her, this is Monique. She was the oldest. Pierre used to tell me that he would look at this picture, carried in his uniform’s pocket, to give him strength whenever he was feeling blue. It gave him the courage to keep going, to come home.”

We both smiled. My heart clenched in my chest as I looked at my great aunt, allowing just for a moment, the grief to overwhelm me.

“I miss Monique,” I said.

“I do too,” answered dad.

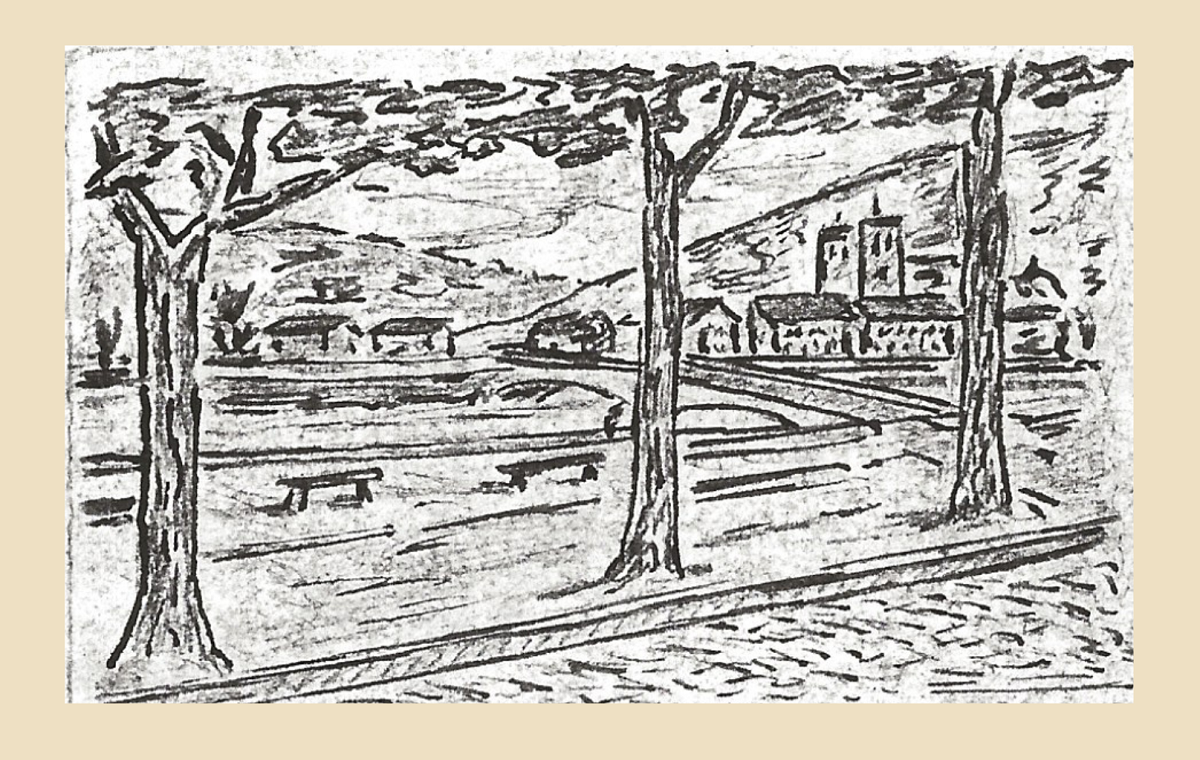

I grabbed a drawing of a field. Across it, there was an old ink stamp. It had faded with time but one word was still readable: “Kommandanture”.

“Near Metz, there was a double frontier guarded by German soldiers,” dad said. “Pierre was hiding in the bushes with Louis, waiting for dawn to cross the second line. They were tired and desperate to come home. Then they heard barking and the sound of combat boots. They were captured at five in the morning.

The German guards took them to the command post where they were searched. One of them found Pierre’s drawings and took them to be examined by the Kommandanture because they thought he was a spy.

After this one, there’s no stamp. Like on this one.”

The drawing he showed me displayed the barracks neatly aligned. My father laid it down next to the page with the two soldiers in Stalag XII-A.

As we kept looking, I took a page with the words “Stalag 325” scribbled in the middle. The light had faded, and the attic was growing darker.

“We’ll finish tomorrow. Let’s go back downstairs,” announced my father.

I sat on the couch while he opened a bottle of red wine.

“So after being arrested, Pierre was sent to Rawa-Ruska,” I said, trying to piece everything together, “but after that…” I glanced inside the box and I couldn’t see another drawing of a camp, just one of a hospital room. “What happened?”

I took a glass and waited for my dad to sit down across from me.

“A few months later, the camp was opened to organisations such as the International Red Cross Committee. They first allowed the ‘rich’ soldiers to receive packages of food. It wasn’t much but it was luxurious in comparison to the small amount of gruesome food they received at the camp. They also allowed detainees to receive medical care. Pierre met a French doctor who explained to him that if Pierre were to get sick, they could send him back to France to get proper medical care. The doctor indicated to Pierre that the Red Cross and the medical personnel coming with it, would be back in two weeks.”

My father repressed a smile and said: “Actually, there’s a famous story in the family about how Pierre managed to come back to Mosnes. Did your grandfather ever tell you about it?”

I shook my head and waited for him to continue.

“After that doctor came to visit the camp, Pierre queued to access the only source of water on site. Every other day, he put his head underneath the camp’s single tap and would let the freezing water fill his ears. The day before the return of the doctor, he worried that his ears weren’t dripping enough to qualify for a return home. He queued one last time at the tap, making sure that he would get an aggressive infection. The head of the camp signed the doctor’s request to transfer him to a hospital. He was diagnosed with double chronic catarrhal otitis. It was so severe that it impaired his hearing permanently. They returned to France by a train and Pépère always loved to describe the moment he first laid eyes on that train.

“It was clean and filled with beds and seats, unlike the one that brought him to Ukraine. He was sent to Rawa-Ruska in an animal compartment, closed and surrounded by 40 other soldiers. Imagine how he must have felt when he realized that this was a train designed for humans! What delightful comfort that implied.

“At the time, trains were given names to identify them. On the one that saved him and brought him back to France on the 21st of June 1943, the painted letters spelled out: ‘Roland’.

“Roland became the second name of my dad – your grandfather – and when I was born, it became my second name as well. This is the last drawing of his journal.”

He handed me the piece of paper.

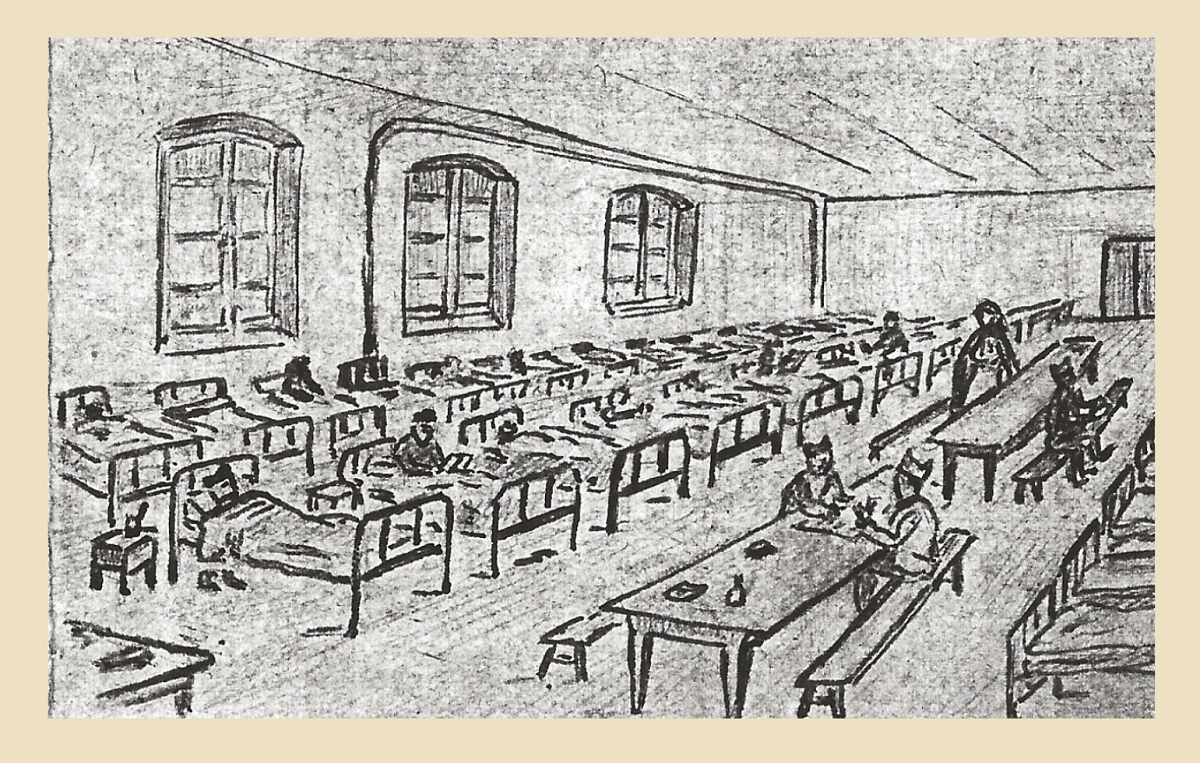

Pierre drew the inside of a hospital room from Saint-Joseph’s Hospital, in Paris. About eight beds were aligned, facing eight other beds. Some of them were occupied by faceless patients, probably rescued from prisoner camps. Pierre accentuated the shadows of the beds on the floor, the sun was filling the room in a similar way to how it had penetrated the attic earlier.

“When he came back home, he met his third daughter, Claudine. And later Claude was born, your grandfather. Pierre put his drawings and memories away.

“It wasn’t until much later, around 1985 or maybe 1986 that he picked them up again, compelled by the need to write a few notes, and add a few drawings so that his many pages and sketches would make sense. With these notes and pictures, he hoped his children and grandchildren and everyone after them could remember his journey.”

What happened in the town of Rawa-Ruska, and other parts of western Ukraine and the former Soviet Union, is one of the least-known parts of the Holocaust. But in recent years, researchers from the organisation Yahad-In Unum have sought out eyewitness testimonies to unearth the history of the Second World War in Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania and Moldova. Their work has led to the installation of a monument in Rawa-Ruska, as well as in other towns, and an interactive map of testimonies, to remember thousands of Jewish people who were killed, many gunned down in mass shootings or transported to the German death camp in Belzec, Poland.

Read more:

- Britain and the League of Nations: all queasy over Europe?

- What has the EU ever done for us? Peace

- La Petite Rockette: The short-term contracts at the heart of France’s civil society

All sketches and photographs provided by Camille Aymond.