I arrived at Liverpool University as a student in 1968 with fire in my belly. I had just emerged from a year in Uganda on Voluntary Service Overseas. It had been a cathartic experience. Until Uganda, I had never even been on a plane, nor left the shores of the United Kingdom. It was there, at eighteen years old, that I had been jolted into life, teaching in a remote secondary school on the banks of the River Nile, some fifty miles north of Lake Victoria.

I had been an indifferent schoolboy who had excelled in no academic subject, but who loved music and painting. Yet just a year or two on, here I was suddenly cast in a position of huge responsibility. My class sported some 60 adolescent O-level students. I was suddenly teaching them everything from Biology to English.

The experience changed my life. It had allowed me to live for 12 months in a community of Africans. I had shared their music, their exuberance and their poverty – their extended families and communities too. Above all, I had looked North from the South and been enraged by the scale of inequality I had witnessed.

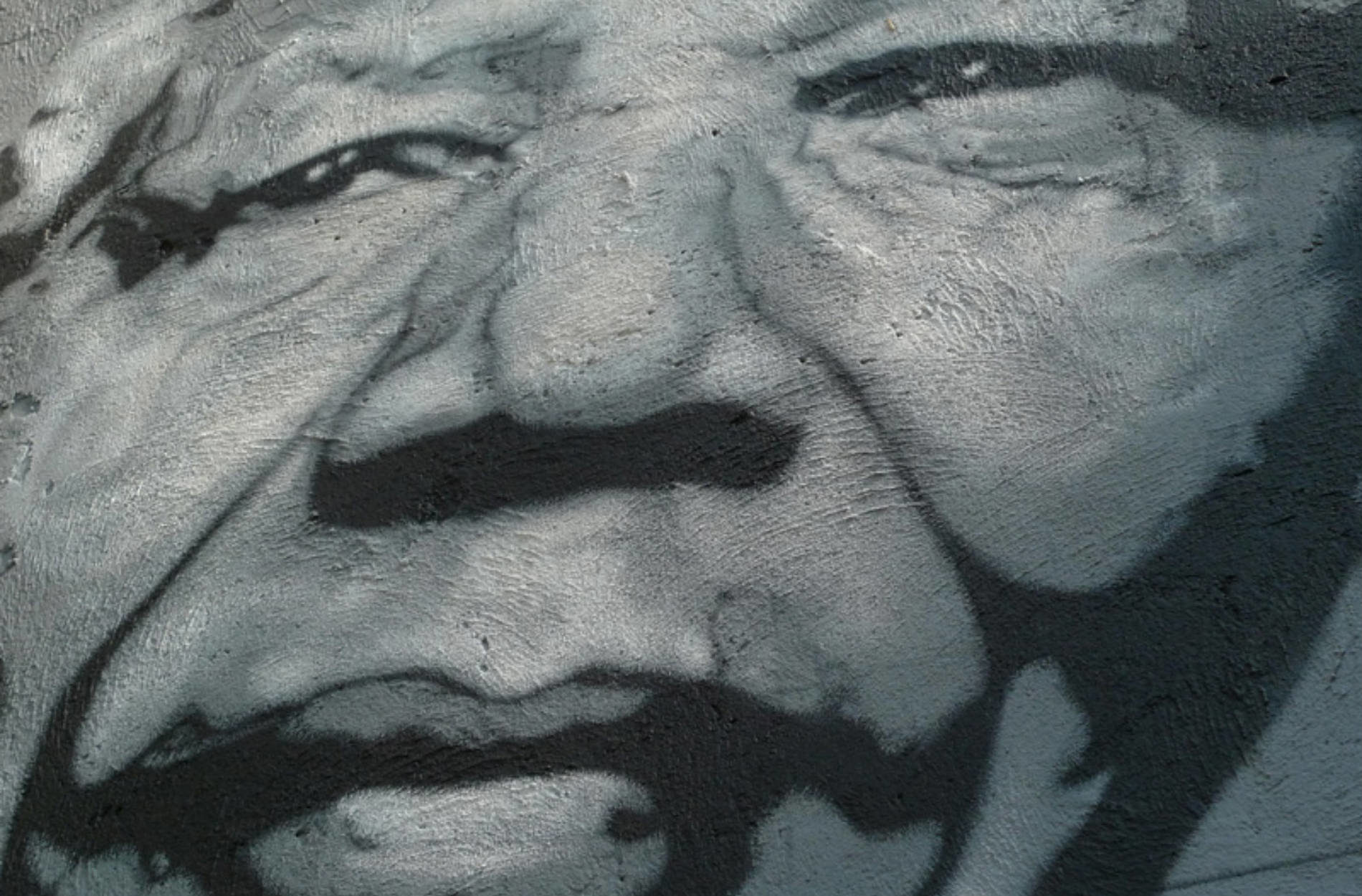

I was a natural then, when the call came, to join the attack on the Springbok Rugby tour of 1970 (the ‘Stop the Seventy Tour’). Mandela had long been my hero, the oppression of South Africa’s black population chimed with so much that I had learned and experienced in Uganda.

The oppression of South Africa’s black population chimed with so much that I had learned and experienced in Uganda

At first I raged on the floor of the Student Union debating society. Then I surged with others around the local branch of Barclays Bank – seen then as emblematic of capitalism’s dark pact with Apartheid. I tried to hide the fact that my own student overdraft continued to lurk within the self same bank.

Then came the day when the Springbok Rugby team headed to Manchester’s Old Trafford pitch. We went by every means possible, clattering down the East Lancs highway. We were determined to dig up the pitch. In the event, I never got near a spade let alone the pitch itself. We fought desperately with police lines to try to get through. Eventually I was arrested and confined to a cell with twelve others.

But now we wanted the University to disinvest its holdings in South Africa. The authorities would hear nothing of it. So we occupied their administrative offices. Six weeks later, when the vacation beckoned protestors home, the Vice Chancellor charged ten of us with bringing the University into disrepute. We were inevitably found guilty and sent down.

Twenty years later, I was finally allowed to enter South Africa for the first time. I stood at the gates of Mandela’s prison reporting his walk to freedom. Suddenly there he was, clasping Winnie’s hand high. Striding toward us. Tears streamed and streamed down my face. I was changed for all time. Those events, though they have often found me wanting, have informed every aspect of my life ever since. They always will.

Photo by Abode of Chaos ![]()