Statues are falling, but what about buildings with a racist history? Should Fayetteville’s Market House be demolished or preserved? In Fayetteville, North Carolina, the birthplace and hometown of George Floyd, there stands a beautiful building with an ugly history. Over the last two years, Black Lives Matter protests have highlighted the troubled symbolism of Fayetteville’s Market House, which was once a slave market and later co-opted by white supremacists. Historian Susan Breitzer finds a building is not as easy to remove as a statue.

Some fear that the removal of Confederate statues – around 150 have been removed across the Southern United States during 2020 and 2021 – will erase history.

But the truth is that statues of value – financial or historical – can be relocated to museums, where they can be displayed with proper context.

And while a statue generally honours and glorifies one individual, a building is much more complex in its purpose. And that purpose can change over time.

Physically and logistically, the removal of a statue is unlikely to impact a community the way the removal of a building, like Fayetteville’s Market House, would.

These are the issues at the heart of the debate in George Floyd’s hometown in North Carolina. The Market House, in the centre of the city, is uniquely complex in that the issue is not its naming, as is the case with many university and government buildings that are named for Confederate figures, but its very existence.

A TOXIC PAST, A TURBULENT PRESENT

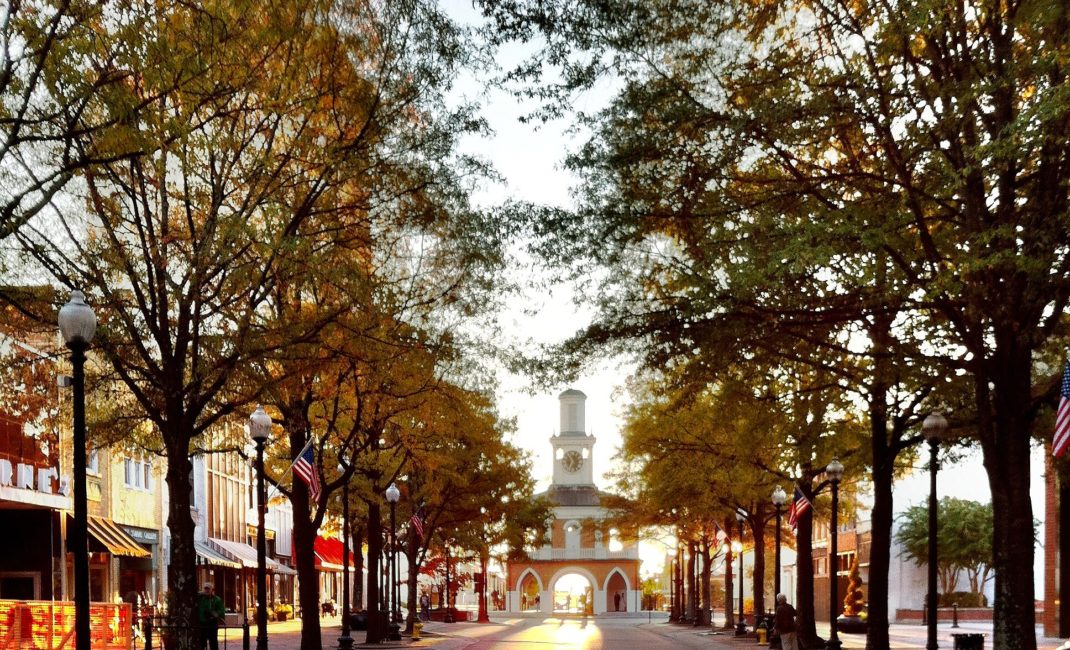

The Market House, first built in 1832 by Black workers, is the only National Registered Historic Landmark in Fayetteville..

Built in the style of an English town hall market, and long regarded as an architectural gem, it features an open arcade on the first floor that historically served as a market space, and an enclosed second floor that originally was the town hall. There is a cupola on top, containing a bell that was once rung multiple times a day, including, for much of the building’s early history, a 9pm bell signalling the curfew for slaves.

Fayetteville Market House in black and white – by Jalexis Photography.

It was intended to be a general marketplace. Slave sales were only a part of its commerce, and enslaved people, in turn, went there to buy goods at the bidding of their masters.

While slavery was an indelible part of the Market House’s pre-Civil War history, its postwar history has been more complex. Immediately after the Civil War, the Market House became a symbol of freedom for newly emancipated African Americans, for a time serving as their gathering place and as a site of political rallies and Fourth of July parades.

Read more: How are different countries removing or responding to slavery statues?

There was a 12-year Reconstruction at the end of the Civil War when attempts were made to redress the inequities of slavery. But efforts to reverse the Reconstruction solidified the Market House’s association with white supremacy, including the continued ringing of the curfew bell even after the end of slavery.

The Market House was the scene of the 1867 lynching of Archie Beebe over an accusation of sexual assault against a white woman. And as late as the 1960s, a local pro-segregation radio show aired under the title ‘Around the Market House’.

There have even been efforts to deny that the building was ever a slave market, most famously during Eleanor Roosevelt’s visit to Fayetteville in the 1930s, when she asked to see the “slave market” and was told not to call it that by her tour guide.

Today, the Market House has become a symbol of the city, with its image on everything from official letterheads to garbage bins – although there has been a recent effort to phase these images out. There is even a miniature of the Market House decorating the roof of the city’s VA (Veterans Administration) Hospital.

The rise of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in the wake of George Floyd’s murder has brought the issue home as never before. Firstly, there was an attempt during the earliest BLM protests to burn down the Market House.

Since then, volunteers have painted the slogans “End Racism Now” and “Black Lives do Matter” – the latter a compromise between honouring the message of Black Lives Matter and distancing from the movement – on the no-drive lane of the roundabout surrounding the Market House. Some have expressed a wish to see the creation of a separate plaza for a social justice mural, similar to that in Washington DC.

Beyond slogans, the Market House had become a gathering point for anti-racist protests. And the same day that the slogan-painting began, the City Council finally voted to remove all remaining images of the Market House from city property.

THE ARGUMENT FOR DEMOLITION

The most forceful voices in favour of removing the Market House have included religious leaders from the city’s Black churches.

Reverend Christoppher D Stackhouse, who delivered a eulogy at George Floyd’s funeral, was a leading voice in favour of demolition. In an opinion piece he wrote for the Fayetteville Observer, he said: “The Market House is rooted in place by racist history, not noble history. This is an uncomfortable truth that will not garner the support Market House advocates desperately crave from Fayetteville’s citizens.”

Rev. Stackhouse rejected any possibility of preserving the Market House, arguing: “We have whitewashed the shameful history of the Slave Market House long enough. Let’s free ourselves of it.”

Before George Floyd’s death, there was a long history of peaceful – and not-so-peaceful – protests to get rid of the Market House, all to no avail. A Change.Org petition that gained more than 125,000 signatures emphasised the pain the structure caused to the city’s Black residents. A counter petition to save the building secured just one eighth of the support, with 15,000 names.

The original petition declared that “the market house [sic] building is a reminder of slavery and fuels white supremacy. It should be replaced with a beautiful landmark funded by an annual city or state grant,” reflecting a desire for an appropriate commemoration of the site and its history, that does not glorify slavery.

Some argue that demolishing the building poses the risk of erasing a history that needs to be known and acknowledged in all its pain and brutality. They claim that repurposing the Market House in the service of racial justice is difficult, but not impossible.

Future possibilities laid out for the Market House range from an educational and cultural centre to a memorial to Fayetteville’s native son, George Floyd. Could a thoughtful repurposing of the building be the perfect triumph over the white supremacy that has so long tainted it, reclaiming a hated symbol in the service of social justice?

THE ARGUMENT FOR PRESERVATION

Demetrius Haddock of the River Jordan Council on African American Heritage, in the Fayetteville Observer, proposed “researching additional narratives” about the Market House (including the role of free Black people in its construction) so as to make the site “a place of historical truth”.

Haddock recommends updating and revising the memorial plaque to emphasise the strength and resistance of those who were enslaved, as well as the Market House’s place on the route of Emancipation Day parades. Above all, he says repurposing the Market House should be about remembering the names of those enslaved and honouring their descendants, as well as recognising how much the Market House is a site of national, and not just local significance.

Also speaking to the Fayetteville Observer, Ashanti Bennett, general manager of local performing arts association Sweet Tea Shakespeare, says making the Market House into a museum is a great idea, but argues this museum should be about more than slavery.

Bennett believes it should present a well-rounded story of the Black experience in America, one that moves beyond injustice to allow for expression of Black joy, and recognise that there is more to the Black story in America than suffering and oppression.

She says:

There are beautiful, loving, creative, nuanced, and joyful stories of the Black experience that almost never get told.”

FINDING A FUTURE

While everyone has an opinion, most Black Fayettevilians seem to be in favour of demolishing or removing the Market House. The comparative petition support is stark.

So, the recent decision of Fayetteville’s first majority Black City Council to vote against demolition or relocation may not reflect the views of the majority of the city’s Black citizens.

Fayetteville Market House at sunrise – by Jalexartis Photography.

The Council has presented several options, including a museum of Fayetteville history that spotlights Black contributions, an event space, a centre for art and Black history displays, and most interestingly, returning it to its original purpose as a market space, except now strictly for Black vendors.

Could this decision be a case of realpolitik? The council is currently facing questions about the restructuring that made its diversity possible.

We can only be sure that the decision will not resolve this contentious issue. But it could be the first good-faith effort to acknowledge this building’s painful history when deciding its long-term fate. And a well-thought-out repurposing of the building—ideally one that both addresses the past and seeks to promote justice for the future—could win over at least some opposition in time.

Any resolution will surely have to honour the many diverse viewpoints of Black Fayettevillians to ensure history and its scars are no longer swept under the rug.

Main image by Jalexartis Photography.

Read more: