Students Allison Leung and Ashley Wong saw for themselves the backlash against face masks in the UK before returning home to Hong Kong where masks are normal and expected. Here, they explore what caused the East-West divide in opinion on face masks – and ask whether the pandemic could change the philosophy and fabric of the UK and US to make them less individualistic and more community-minded.

Growing up in Hong Kong, we became familiar with face masks worn for hygiene or even for fashion. When Covid hit the UK last year, we put on our masks just as we would at home. But we soon realised how unusual that was.

Quickly this little piece of fabric became controversial, sparking a strong anti-mask sentiment among some and a nationwide public debate about freedom.

In an age of globalisation when culture seems to matter less and less, the pandemic has made some cultural differences visible and stark.

Face masks are now a regular sight in shops and streets around the world. But at the start of the pandemic, particularly in the UK and the US, they were viewed with suspicion and mistrust.

In February 2020, an Asian woman was assaulted in a New York City subway for wearing a face mask. In March, two teenage girls were arrested in Southampton for an alleged racist attack on several Chinese people wearing face masks. And in May, a Chinese student and his girlfriend were assaulted when grocery shopping in Sweden while wearing face masks.

This small piece of cloth, which started as a simple barrier against the novel coronavirus quickly became the source of a heated worldwide debate about public health and personal autonomy – and behind the debate lies a culture clash.

In Asia, even prior to the Covid pandemic, people are frequently seen in public wearing masks. They are worn to protect the health of other people when the wearer has a cold or to filter polluted air and pollen. A survey in Tokyo found some people wearing masks as a fashion accessory.

The first Covid cases were reported in China in late 2019, and by the end of January 2020 a mask frenzy had swept the nation. In Hong Kong people were seen queuing outside pharmacies overnight amid citywide mask shortages. This desperation can be explained by the legacy of SARS.

In 2003 the deadly respiratory disease turned the metropolitan city into an eerie ghost town as its inhabitants isolated at home, shielding from one another. Since then, people have developed a habit of wearing surgical masks to prevent the spread of contagious diseases.

Young people wearing face masks at a food stall during the Covid pandemic in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, China – by Joshua Fernandez

In the Far East, shoppers exercise caution over the masks they buy by checking their proven filtration efficiency. And during the Covid pandemic, the social stigma against those who choose not to wear a mask is evidenced by disapproving glares and refused entry to stores. In the West, however, when Covid first hit, Europeans and Americans took the opposite approach.

For many, face coverings were a brand new and quite bizarre public health practice. And the effectiveness of face coverings in preventing the spread of the novel virus was hotly debated – partly fuelled by inconsistent messaging from the World Health Organisation (WHO) and governments.

TO MASK OR NOT TO MASK?

WHO first advised that only those who are sick and showing symptoms and those caring for someone infected should wear a mask. Early in the pandemic, WHO was criticised for its inconsistent advice on masks. It wasn’t until last June that the WHO changed its advice, saying masks should be worn in public.

In the US, for months President Trump insisted that masks would not suppress the virus. Then in August, he changed tactics, telling supporters that “despite some confusion” face coverings could help prevent the spread of the virus and that wearing a mask was the “patriotic” thing to do.

Despite this newfound caution, in the first presidential debate, on September 29, President Trump mocked his rival Joe Biden for wearing a face mask. Three days later, the President tested positive for COVID-19.

Man holding a sign during an anti facemask protest amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. Ohio, United States of America – By Becker1999

The UK government, while desperately trying to source personal protective equipment (PPE) for NHS staff, initially denied the effectiveness of face coverings for the general public. In May, on the same day the UK government’s Scientific Advisory Group of Emergencies (Sage) advised against physical contact, Prime Minister Boris Johnson boasted about shaking hands “with everybody” at a hospital with coronavirus patients.

Advice about the wearing of face masks in the UK was also inconsistent, with London Mayor Sadiq Khan lobbying for mandatory masks on public transport in April when the UK government was still advising against face masks for the general public.

They later relented, making face coverings mandatory on public transport in England in June and in shops by the end of July.

TWO SCHOOLS OF THOUGHT?

Can these different national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic be explained by two polar schools of thought: collectivism and individualism? While collectivism prioritises group conformity and places a greater emphasis on community and societal traditions, individualism encourages the independence and autonomy of each individual person.

Of the many theories behind the reason for such cultural differences, one commonly agreed defining factor relates to growing food. The theory suggests that cultures which have historically depended on rice as their basic food source are more co-operative and interconnected because farming rice paddies (before modern irrigation systems) required collective labour.

Wheat, barley and corn, on the other hand, could be grown on a smaller scale. These cultures are individualistic because self-reliance is rewarded.

Signs at an anti facemask protest during Covid-19 pandemic. Sheffield, UK – by Tim Dennell

Emma Teng, Professor of Asian Civilizations at MIT, argues too much has been made of the supposed difference between Western “individualism” and Eastern “collectivism” during the pandemic. Instead, she quotes her MIT colleague Prof Yasheng Huang who believes communitarian norms in East Asian countries support the ethos that “doing something for the community good is good for me also” – a value known as 公德心: in Mandarin, gongdexin; in Japanese, kootokushin; in Korean, kongdkshim; and in English, public-spiritedness.

When news of the new virus emerged from China, Asian cities responded with near-universal mask wearing, seeing this as a responsible way to protect oneself and others. It was not just about “me”, it was also about “us.”

The belief was that masks should be worn by each member of the public and we should respect social distancing rules for the benefit of everyone. Our collective efforts would flatten the curve and help bring our lives back to some degree of normality.

Women wearing masks at a Japanese street food market. Ueno, Taitō, Japan – by Jérémy Stenuit

But Western cultures appear to have placed a greater emphasis on “me”. The pandemic is clouded by politics and personal freedom. Social distancing rules and mandatory mask wearing are branded an infringement on individual liberty.

The US saw protests against wearing masks and violence when such laws are enforced. One Florida resident told a public meeting: “I don’t wear a mask for the same reason I don’t wear underwear – things gotta breathe.”

People holding sign during anti facemask protest amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. Sheffield UK – by Tim Dennell

THE NEW NORMAL

Over recent months, there has been a remarkable shift in perspective in the West on the effectiveness of masks in the prevention and management of the virus. With growing scientific evidence supporting the use of masks, many Western countries and cities have now implemented laws making it mandatory for citizens to wear a mask in indoor settings.

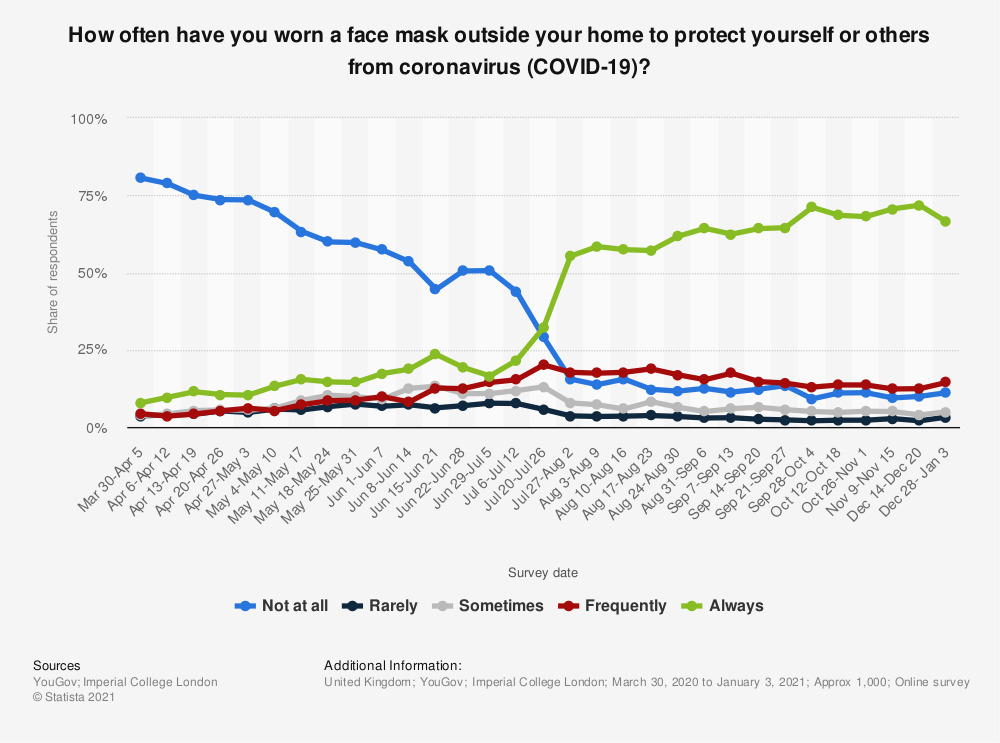

In September, the UK government began screening a “Hands, Face, Space” advert showing members of the public explaining that they wash their hands, cover their face and make space to protect other people. The most recent survey by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) found 95% of adults claim to have worn a mask when outside the house. The same survey in July found just 52% were wearing face masks.

YouGov and Imperial College London graph shows the changing proportion of people in the UK who say they are wearing face masks

So, could the vast scale of the pandemic and the resulting near-universal changes to how we work, learn, shop and socialise, create significant and lasting changes to our societies? Cultural psychologists think so. Some have suggested that individualistic societies may endorse collectivistic attitudes in the future.

One study found that “societal collectivism serves as a natural guard against disease transmission”. So, perhaps “peer pressure” will no longer be a term exclusively used for adolescents. Many who grow up in Western cultures may start to feel the pressure – and benefit – of conformity, practising social distancing and calling out behaviours that harm public interests. And face masks may become a commonly accepted worldwide.

NHS campaign imploring the public to wear facemasks during the Covid-19 pandemic

Main image by Tim Dennell.

Read more: