Nour Ghantous writes about moving to Ireland from Lebanon as a young girl, her experience of “othering”, western beauty standards and cultural appropriation, and her journey to self-acceptance.

When my mother, sister and I relocated to Dublin from Lebanon I was still so young that life in Ireland is all I can recall.

Growing up, it annoyed me that I had to wait so many years for Irish citizenship, just to prove my belonging to the only country that felt like home. My friends wore the badge of their parents’ homemade shepherd’s pie and the tales of their grandparents’ encounters with the Banshee herself with ease and undeniable Irishness. It was harder for me.

My mother didn’t know how to make a shepherd’s pie, but she could make a mean Tabbouleh.

My grandmother told a story from her village in rural North Lebanon, a story about a boy who befriended a snake. In return for protection, he would feed it riz w laban, a staple food in Lebanon of plain rice and yoghurt. It was one of my favourites. But secretly so. Because how could my friends relate when Saint Patrick drove all the snakes out of Ireland? And God forbid they found out about the alien foods that I ate.

From top to bottom: Nala, their mother, and Nour

When we first came to Ireland, and for a brief moment, my sister Nala and I were unapologetically Arab. It didn’t take long to recognise the vulnerability that came with that identity. Like most bilingual four-year-olds, I couldn’t quite differentiate between Arabic and English. During the first few weeks of school, I’d often unwittingly switch between the two, each time inciting more ridicule than the one before. Nala was six at the time and had better control of her speech. But unlike me, she has striking Arab features – dark hair, dark skin, and dark eyes. They called her a “Paki”.

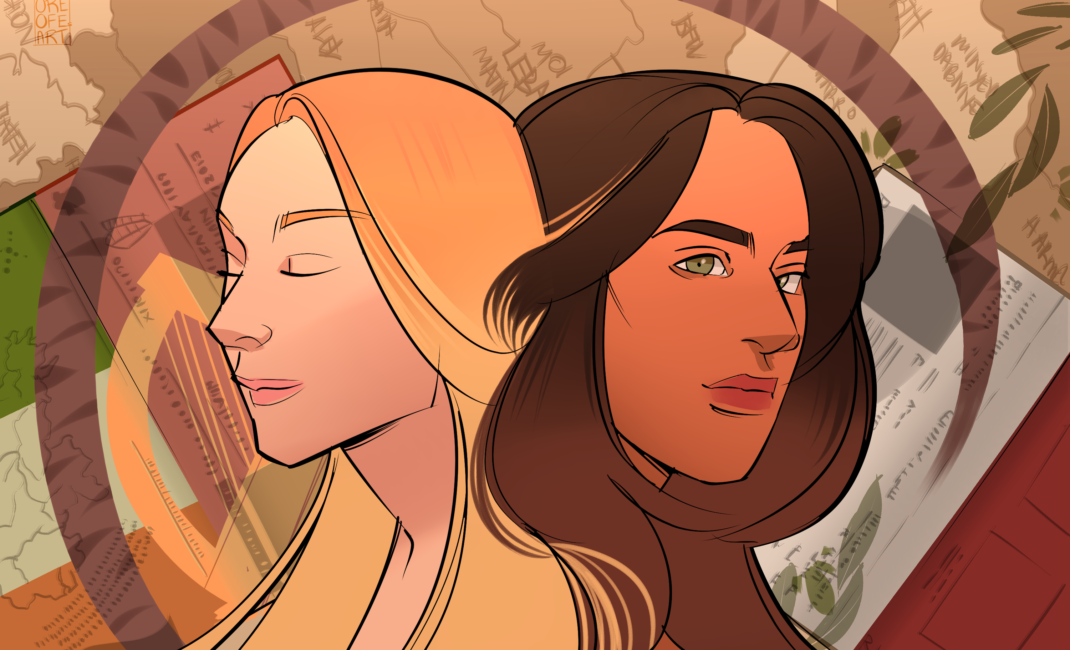

Nour (left) and sister Nala (right).

Hit with the cruelty of childhood a little harder than others, we were left scrambling for the ‘Irishisms’ that would best camouflage our most glaringly Arab facets. Nala immersed herself in curating her physical appearance to suit the young female Irish aesthetic. She started off mirroring her peers with Ugg boots and Juicy Couture sweatpants, but quickly became the innovator for many fashion trends at school.

Her fidelity to beauty and fashion left no room for ridicule, just esteem. I wanted to be able to communicate at the same high standard as my peers so I devoted myself to linguistics: reading, writing, and performing. I surrounded myself with the Irish language, competing in Gaelic debating and poetry competitions.

When I was told that I was the only student that had received an A-grade in Irish for my Irish junior certificate, I cried with joy. I would have never dared to speak a word of Arabic when another soul was in earshot. We were finally naturalised as Irish citizens when I was 13. The three of us huddled in my mum’s Nissan Micra, giddy with the prospect of unrestricted travel and identity.

Mum rifled through the documentation to get to the good bits, sending a flurry of papers towards me. One sheet landed on my lap and naturally, my eyes were drawn to the bits as Gaeilge – the certificate of citizenship.

It was Nala’s. It read: “This is to certify that Nala Ghantous is an Irish citizen, born in Libya”. This confused me and so I read it again, translating each word as I went along: “Li-bi-ia”.

“This isn’t right,” I told my mum, who questioned whether Lebanon might just sound like Libya in Irish. But I didn’t question it; I knew my Irish. And I knew the certificate should have read “Liobáin”.

The irony was shrill. I was a stranger to the language that I knew so well. I had meticulously acquainted myself with its derivatives and origins, its politics and its importance to the preservation of Ireland’s culture. But my love of this nation proved to be unrequited.

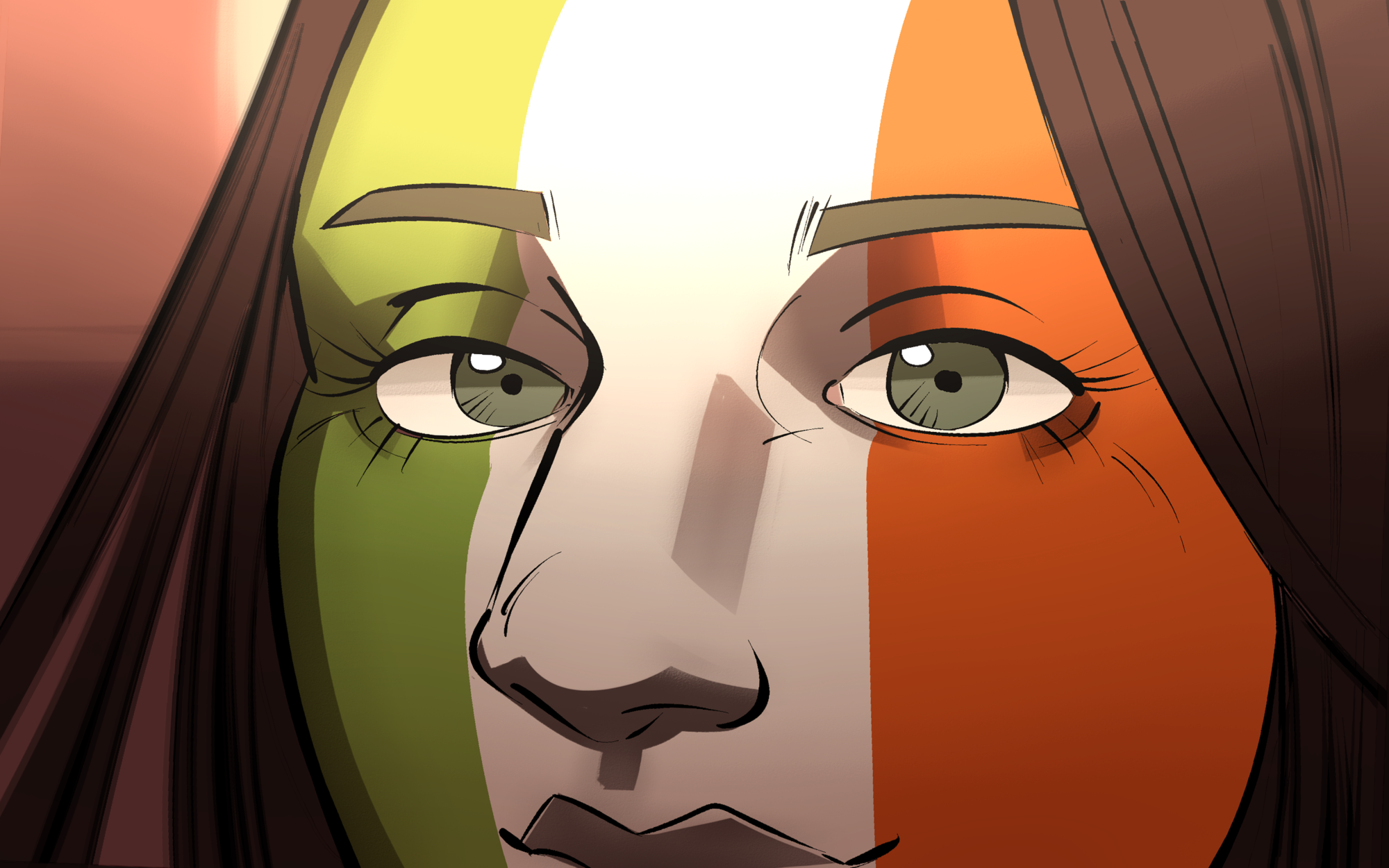

Nour with her face painted in the colours of the Irish flag at a St Patrick’s Day parade

And the reality is that I will always be a stranger to the Irish. It doesn’t matter that I have the passport, or the proficiency in Gaelic, or a Dublin accent. Because “Irish” is a term that embodies both an ethnicity and a nationality. You can be an Irish national, but unless it’s in your blood, you can never truly be “Irish”. I realised my DNA is something I can’t change. And I no longer wish to.

Read more: The Foreigner – one family’s journey from Pakistan to the UK.

I used to resent the fact that I couldn’t be white, and by default, couldn’t be Irish. But my understanding of the years of oppression and disadvantage that Irish people faced has grown. My white Irish friends are not so different to me. They aren’t just ‘white’. They’re a minority and I think it is important that they are able to define themselves and their own ethnicity.

The part that frustrates me is that defining “white Irish” as an ethnic group means excluding the growing definition of culture in Ireland, which leaves room for discrimination against non-white Irish people. This is most obvious to me when I fill in surveys or forms that ask me to self-describe my identity. Under “Irish”, there are always variations of white identity to select (American, Traveller, British). Beyond that, I most often find “Arab” listed alone underneath “other”.

Nour as a little girl

Yet where language and discourse has failed to welcome newcomers, some would say that Irish beauty standards have expanded to include foreign ideals. Multiculturalism is growing in Ireland, and Dublin in particular, whether the nationalists like it or not. Communities of varying origins have woven a thread into the generational fabric of the country.

Take St Patrick’s Day – an event that has become globally recognised as a celebration of Irish culture. For years, parades across Ireland have not only featured trad music and Irish dances, but drum-beating Punjabis and West-African dancers too. International culture is undeniable in Ireland, and this is seemingly mirrored by the Irish beauty and fashion industry.

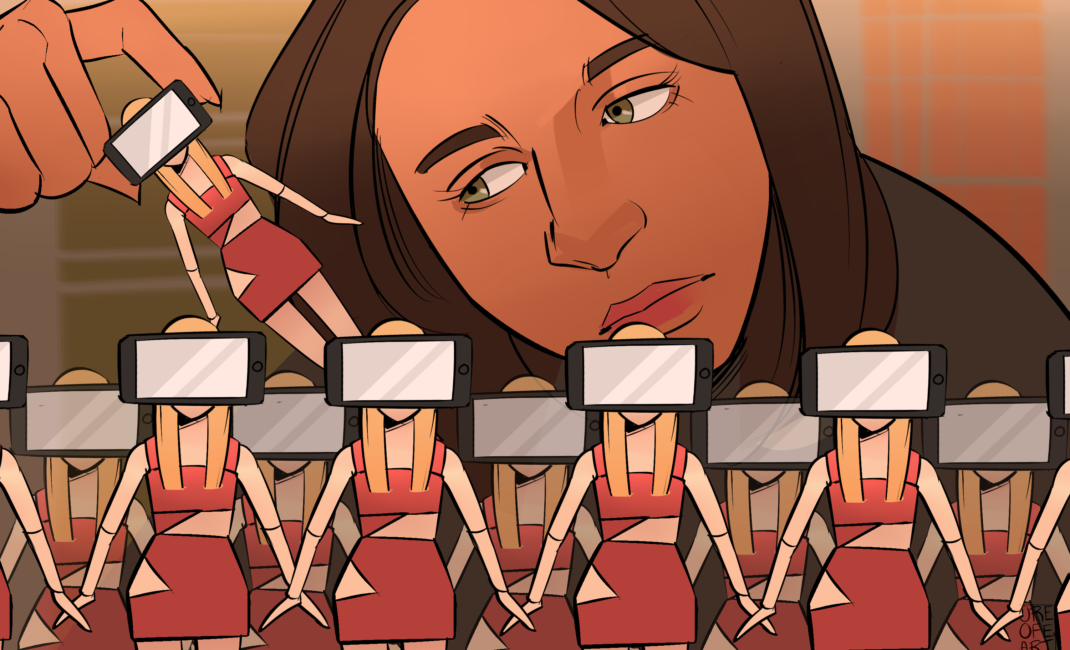

But the growing trend of non-white features in the beauty and fashion-sphere seems only acceptable when presented by white influencers.

When I was at school, the other girls would tell me how jealous they were of my “tan”, while at the same time laughing at the length of my eyebrows. They would mock my middle eastern nose but talk about how they wished they had curves like Kim Kardashian.

When powerful white influencers adopt “ethnic” beauty, it’s not so much about appreciating a culture as appropriating it and branding it as their own. Because of the underlying whiteness of it all, influencers can pick and choose aspects, leaving crucial cultural characteristics behind.

This trend perpetuates the destructive beauty ideal of the “ethnically ambiguous white person”. It leaves us “ethnic” people in an uncomfortable purgatory where we not only feel “not white enough”, but also “not the right kind of ethnic”.

Throughout the 2000’s, and even now, Irish schoolgirls and young Irish women have committed themselves to the practice of ‘fake tanning’ to darken their complexion. Growing up, I felt like I had a free pass out of this tedious custom. My collars were never stained, and I never worried about looking ‘too orange’. It was different for Nala. Being already darker than her friends, I never understood why she felt the need to slather on layer after layer of the stuff. When I was younger, I thought it was because she had forgotten she was Arab and genuinely believed she was Irish. The reality was that she believed she “wasn’t the right kind of dark”.

Nala as a little girl

One of the myriad issues that come with cultural appropriation is that somebody’s own image is taken from them and transformed into something beyond their reach. Emma Dabiri, fellow Dubliner and author of Don’t Touch My Hair and What White People Can Do Next, helps to differentiate beyond cultural appreciation and appropriation plainly:

Girls who fake-tan are not culturally appropriating anyone, in my opinion. They’re buying into a trend to reinforce their sense of belonging and acceptance in society. They look to their favourite celebrities and influencers for reference. They’re not trying to look ethnic; they’re trying to look like white influencers who are trying to look ethnic. Dabiri explains with cultural appropriation: “The structurally advantaged group becomes the primary (financial) benefactor of an innovation that was not theirs.” Instead of using their platforms and followings to amplify the voices of minorities and marginalized people, these influencers are opting to borrow their looks and keep the profit.

Nour with dyed blonde hair

There is something to be said about the power of being pushed away. For years, I searched for the camouflage that would allow me to say that I was Irish and be believed (and believe it myself). This meant hiding a large part of who I was. I never felt anything close to belonging, whether I was allowing friends to believe that I had an Irish parent or bleaching my hair to oblivion. It took years of rejection for me to question why I thought external validation would afford me an identity, and as soon as I did, I realised that the most powerful acceptance came from within.

This is a realisation that I am lucky to have made. The benefit of sitting on the side-line is the view. Indeed, growing up in Dublin was harder for me because of the unattainable beauty standards and the negative discourse surrounding foreigners. Yet, I have observed that the societal expectations that make people of colour feel inadequate do a similar thing to most other people as well.

Not being white meant knowing that some standards were truly unattainable, and that I could stop trying. Through the chaos of childhood and adolescence, I felt grounded in knowing that I had a unique identity. I see my white friends struggle with theirs like my younger self did when she felt she didn’t have a place in society. Having my differences regularly pointed out left me with no choice but to accept my individuality and unlearn my desire for conformity. My white friends did not get that privilege.

All illustrations by Oreofe Morakinyo.

Read more: