Using her experience of the nightlife industry, DJ Kate Williams explores how clubs and bars can tackle spiking and sexual assault. Did the Girls’ Night In protests make any difference? And what can be done to make nightlife spaces safer for women?

Somewhere on a dancefloor, Friday night becomes Saturday morning. One hour bleeds into the next as beams of light illuminate a crowd. Lasers highlight pockets of reckless abandon, technicolour glimpses of individuals held together by the rhythm of a 4/4 drum. The numbers grow into an endless sea, bodies animated by the sound, as though engaged in the ecstatic ritual of an ancient civilisation. A scene that plays out night after night, drawing people from their every day on the promise of music and good times.

As a DJ and regular club-goer, I am more than familiar with a night’s development. I watch venues transform, following the journey from empty room to sensory overload and back again. It’s something I’d come to think was inevitable, like the ebb and flow of the tides. That was until the unprecedented nationwide disruption. Disruption that after months of closure due to Covid-19 no nightlife brand would have predicted. Suddenly, some of the UK’s most popular venues were abandoned by their student regulars, with some venue owners opting to close altogether.

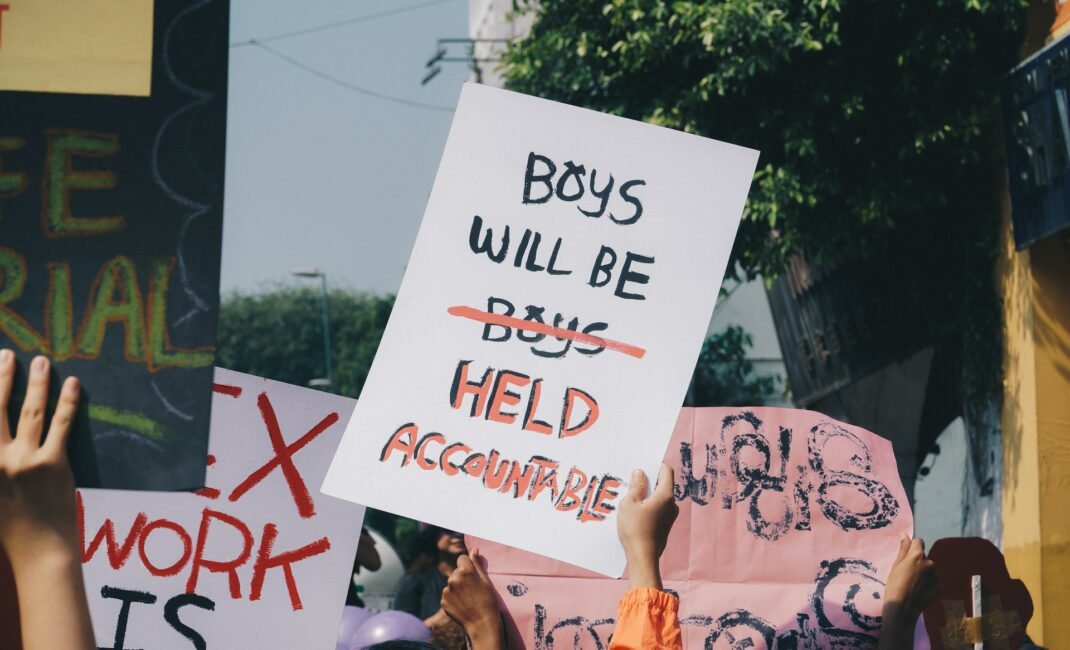

This action came from Girls’ Night In, a student-led movement, formed in response to concerns about spiking. A boycott was called, spanning 50 cities, encouraging people to avoid bars and clubs in protest of venue conditions that facilitate the behaviour. The movement intended to hit venue owners financially so they would collaborate on solutions.

View this post on Instagram

As a DJ and regular club-goer, I am also more than familiar with watching my back. Spiking is no new problem though. The practice has been recorded for over a century, and many will recognise the regular ‘Watch your drinks!’ Friday night caution given by parents as their youngsters wander out into the night.

Limited data makes it difficult to say whether spiking has increased, but it’s clear that some are more worried than ever, especially as reports of spiking via injection circulate in the media and among student groups across UK universities – providing an even more sinister spin on the traditional horror. So, it’s unsurprising that many have been affected by the message of Girls’ Night In, popularised across social media platform, Instagram.

The movement speaks to a relatable experience, so it makes sense that these online profiles have attracted thousands of followers. Many feature remarkable shows of solidarity among wider student populations and those sharing their past experiences of spiking, and other instances of assault. It is the bravery and conviction of these young people that has spotlighted a prevailing issue in nightlife.

Photo by Michelle Ding on Unsplash

They started a conversation, and not the usual kind. I have heard female industry professionals having a private vent about their terrible times in ‘certain clubs’ with ‘certain people’, and I’ve also seen students huddled in the smoking area after having ‘saved’ their best friend from ‘that guy’. But this was different.

This was a public conversation and on a national scale. It gathered collective anger and galvanised, calling for reforms and quickly. The movement published demands of new safety measures, rejecting personal responsibility and laying it at the feet of those with influence. Proposed solutions came immediately, in a way that almost never happens with complex and enduring issues of this sort. It was heartening.

However, months on I ask, what now? I haven’t seen any changes across the clubs I visit and as the momentum of Girls’ Night In threatens to wane, I wonder whether we are any closer to preventing spiking.

To know this requires consideration of some of the progress made so far.

As you’d expected, some nightlife brands engaged more willingly than others. There are examples of Students’ Unions expressing support, closing outlets on boycott nights and publishing spiking action plans. Yet, some venue owners have been resistant. Organisers’ of the Leeds boycott published a video of a staff member from popular student venue, The Warehouse, denying spiking occurred and blaming excessive drinking.

Despite setbacks of this sort, boycott organisers have reported some productive conversations and continue to take a positive outlook.

As I keep my eye on the developing situation, I find it harder to be optimistic. Perhaps it seems easier from the outside looking in. After all, it should be – there is no justification for spiking and there ought to be zero tolerance, whatever the means to this end.

But my time in clubs has shown me how deeply flawed the industry can be and how difficult an issue of this kind can be to unpick. Nightlife is important to me. I’ve had some incredible times that have contributed to making me who I am. And this makes it even more disappointing to have to reflect on its darker side, or hear about how it’s negatively affected others.

Many women and non-binary industry professionals have begun to document their experiences and in turn, some of the cultural problems that may exist at your local student night, as well as at the top of the music industry. These are broad and wide reaching. Some relate to gender-based discrimination by talent bookers for some of the UK’s largest events, others the extraordinary scrutiny DJs can face showing up to a job looking ‘too sexy’ or ‘not sexy enough’.

Photo by Daniel Robert Dinu on Unsplash

There are times when I’ve struggled to be taken seriously, or gain the same respect as my male counterparts. One thing that has followed me over eight years of DJing is the disbelief that I can and do, often from older men but also my peers who mix. As I have come to play more venues for larger crowds, I’ve had my own moments of disbelief, and continue to remark at the number of drunk guys who approach for a “quick go on the decks”, despite never having seen the inside of a DJ booth.

Worse than that, Girls’ Night In are right.

Misogyny can be far less benign and manifest in a world of unchecked sexual harassment and assault, something I have learnt DJs are not immune from.

I wish I could provide some assurances. I’d like to say this behaviour is often perpetrated by the archetypal ‘dodgy’ guy, the type you might find down a dark alley. Or even a well-meaning ‘good bloke’ who just had one too many – whatever society at large might use to justify. However, in my experience, even the classic excuses would fall far short.

I have encountered problematic behaviour from all manner of people, other DJs and even security staff who should occupy a position of trust. This might help begin to describe what I fear to be the problems with some of the ‘solutions’ offered.

In my opinion, there is a drastic need to change attitudes about nightlife spaces, particularly regarding what they’re for and how people should behave there. I think some conflate going out with being “up for it” or as awful as it sounds, “open to persuasion”. No doubt spiking is wrapped up in this ideology, as drugs or extra alcohol can be used to reduce inhibitions or incapacitate.

This is one of the reasons Girls’ Night In has recommended staff training, to ensure those working in nightlife spaces understand what unacceptable behaviour is and how to respond to it. This is necessary. Although, it’s also something that should be considered and implemented carefully.

A recent investigation into nightlife safety campaign, Ask For Angela, demonstrates why. The research, undertaken by Metro journalists, could provide an ill-fated glimpse into the future of schemes to tackle spiking, if they are not implemented properly.

The investigation demonstrated that the scheme is incredibly ineffective, following a test of the code phrase ‘can I speak to Angela?’ and similar over several weeks in a mix of London venues.

When someone indicates concern, staff are supposed to spring into action discreetly to ensure they are kept safe. According to the Metropolitan Police, this might involve taking the individual to a safe place, and helping them – perhaps with assistance to leave or find a lost friend.

However, journalist Tanyel Mustafa was met with a mix of confusion and incorrect procedure, which would have left a concerned customer at risk, without support. This is despite the fact Ask for Angela is supposedly well-established, launching in 2016 and revamped in 2021, with the Met boasting of 400 freshly trained venues.

There are many potential reasons for this. Nightlife venues have high staff turnover which perhaps makes training everybody so logistically difficult that it never happens. Or maybe it’s that no training at all is required to advertise the voluntary scheme. This is shocking, but no more so than the fact that these issues are already known to scheme organisers, who themselves are unaware of how many venues have signed up.

For training schemes to reduce spiking, they’d have to be considerably better than this. An obvious starting point being that a consistent level of training needs to actually be provided. Even then in the best case, a successfully implemented scheme like Ask for Angela relies on the victims of spiking. For it to work, individuals must recognise what has happened to them and able to report this to a member of staff. A task that is incredibly difficult in the circumstances. This jeopardises an initiative’s ability to improve safety, as the damage is done and there is a large likelihood perpetrators will go unidentified. There is also the issue of accountability. It is worth asking whether schemes like this are so often taken up by venues to avoid them having to take other measures. Measures which would require more proactive attempts to prevent spiking and similar incidents.

Photo by Jeff Tumale on Unsplash

I also worry that proposed solutions aren’t truly focused on the problem, or the right problem at least. A priority of Girls’ Night In has been spiking with illegal substances, whether via drinks or injection.

This explains why some have called for increased door searches, the proposal for mandatory bag inspections reaching Parliament. This is in addition to the suggestion of drink testing kits available to customers. It’s a sound logic that if substances don’t get in the club, people can’t be spiked, right?

Again, the reality is more complex. Neglected by many discussions is alcohol spiking, something which experts like Professor Harry Sumnall agree is far more common. After all, it may be as simple as ordering a double vodka when someone wanted a single, and the cumulative effect may be just as serious as spiking with drugs. This is evident in the prevailing link between alcohol and sexual violence.

Any crackdown on illegal substances could have a positive impact, but would have been useless in stopping the vast majority of spiking cases. If the main drug used is enthusiastically sold in every venue, we begin to get the impression that there is no solution here either.

That’s why I believe that the solution lies in the cultural problem mentioned earlier – a culture not strictly confined to nightlife, nor the use of drugs or alcohol. Predatory behaviour is the real issue, spiking is one of its many manifestations, and knowing this makes the solution even more distant. The discussions started shouldn’t be pushed off into the future though. It should be possible to make some improvements to the status quo, even if the underlying causes of spiking will take longer to address.

More conversations are needed if there is any hope of making nightlife safer. So far, there has been considerable engagement from students. A valuable next step might be combining this insight with that of nightlife industry service providers. So far, nightlife has largely been represented by venue owners, but the industry is much bigger. I think that DJs, lighting technicians, bar staff and anyone who might be able to contextualise the issue of spiking could also add a valuable perspective. Many will have an insider understanding of the industry, venue policy and any “unwritten rules” that might influence how well a venue deals with these incidents.

And after all, those who work in clubs are equally vulnerable to problematic cultures and predatory behaviour. This means that understanding their experiences may be essential, not just in pursuing solutions, but helping to better articulate the problem. Engaging as many people as possible can only be useful in this context, as well as across all walks of life where gendered harms occur.

From these discussions, it could be possible to make nightlife reforms more watertight and increasingly capable of delivering part of the cultural change required. Staff training schemes can be developed or implemented more effectively, and perhaps the key to this is more oversight. At the very minimum, it should be possible to ensure help is available anywhere it is advertised. We may also need mandatory training for as many team members as possible, even if schemes providing this will remain voluntary. However, an ideal scenario might be to have policies related to spiking and predatory behaviour taken as seriously as other health and safety issues, related to essential venue licensing conditions.

Ideas like this and whatever comes of further discussion might play a role in dismantling some of the cultural problems that manifest in nightlife spaces. But it is still an uphill battle.

If the nightlife industry can be inherently sexist, it sets harmful standards that are resistant to improving conditions for all who enter.

Unacceptable behaviour like spiking is ultimately a product of wider patterns of socialisation that do not begin or end in the club. For the purposes of addressing the underlying causes of spiking, the issue might perhaps be most usefully considered a facet of wider societal inequality and efforts to combat this. Spiking exists alongside a range of harms, including sexual assault or other violence, the distribution of victim and perpetrator in these incidents often being divided along gendered lines. Among some of the most shocking cases are brutal murders of women at the hands of men, frequent enough year upon year to necessitate the development of the Femicide Census. A project undertaken by Karen Ingala Smith following years raising awareness of these cases on her blog Counting Dead Women. Some may consider spiking and murder to be very far removed from one another, but quite often the ideology that leads to offending of this type is the same. Consider the study from the The University of Kent where 1 in 9 male university students surveyed by admitted to rape or sexual assault, those with misogynistic views being more likely to offend.

So, despite the triumph Girls’ Night In has been for raising awareness and fostering real solidarity, it may succeed at only that for now. It is my fear that some venues might cut corners, adopt ‘solutions’ to spiking that require no effort and do nothing to make things better. They may display a poster and go back to business as usual.

As time passes, the media forgets and with students keen to get back out, society may tolerate this kind of response. How can we keep the conversation alive? In April this year Parliament published the product of consultations on spiking as part of its wider work into violence against women and girls. The recommendations proposed offer various opportunities to keep talking, whether as part of proposed collaborative work with Local Authorities on anti-spiking strategy, other communications as part of national campaigns and in academic research. Wherever possible stakeholders must take these chances, as the proposals may provide a means but are not themselves an end. Solutions must emerge.

More work is needed and the evidence for this is all around. Just this summer there have been more concerning reports of spiking via injection, this time at Leeds Festival where two young women have since described terrifying ordeals, one near fatal. It is also worth noting that these incidents happened at an event with its own campaign calling for a stop to violence against women and girls. This was publicized on the festival website, complete with definitions of unacceptable behaviour like spiking and with links to the police’s online crime reporting tool. It’s clear that while words and good intentions are important, they will not go far enough.

In the wake of the Girls’ Night In boycott, now is the time for sober reflections on the conversation so far to ask how we can close the gap between our current reality and the vision of a safer society for everyone.

Featured image by Pim Myten on Unsplash

Read more: