“Women are being killed, we’re dead inside” Firoza Wahedi took an oath to protect women’s rights in Afghanistan. The Taliban takeover forced her to flee, but, starting a new life in Italy, she says no one will silence her voice.

When the Taliban launched a large-scale offensive in 2021, rapidly overwhelming the national army and capturing province after province, Herat, Afghanistan’s third largest city, was one of the first to fall.

Herat-based activist and advocate for women’s rights, Firoza knew it was time to leave. As the president of the NGO “Moassese-i enkeshāf-e eghtesādi, ejtemā’i wa warzeshi bānawān” (Women’s Economy, Social and Sport Development Organization or WESSDO) Firoza had promoted women’s participation in sport and helped build health projects in an area which has always been affected by very high child and maternal mortality rates. She knew the Taliban would have no mercy on her.

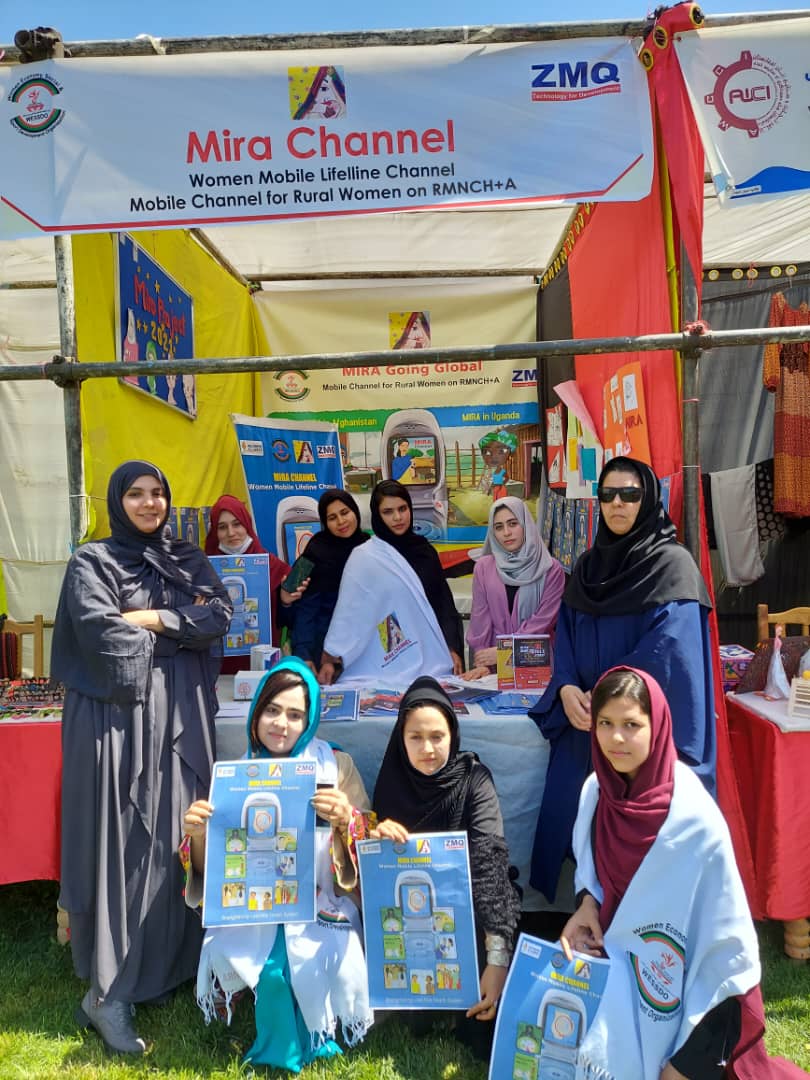

The WESSDO organisation.

“Before the Taliban seized control of Herat, I had been working with women for twelve years, supporting them to take part in sport competitions and coaching them how to play cricket,” Firoza recalls. “I also acted as a consultant for women who wanted to start their own businesses.”

Sitting on a small chair in the living room of her new apartment in Friuli, Firoza smiles as she pours green tea into little white cups: Afghans are famous for their hospitality and she is no exception, offering up chocolate biscuits.

Although she fled Afghanistan to save her own life, Firoza has not forgotten what Afghan women have gone through and vows to keep fighting for them from afar.

Firoza Wahedi training a group of girls at a basketball pitch.

“I want to tell my story and those of other women, so that the world cannot forget my people.”

A PERILOUS JOURNEY TO FLEE THE TALIBAN

“Our work with women was our fault in the eyes of the Taliban and for this reason we could not live in Afghanistan. Some of my friends were killed by the Taliban because they didn’t find anywhere to hide.”

Firoza escaped from the country with her friend Fariba Baluch. They were at Firoza’s office when they heard shelling: mortars were hitting the western city of Herat, and fire was spreading through roads and buildings, throwing its inhabitants into despair.

The two women clung one to the other, trembling, in a small corner, fearing for their lives and those of their loved ones. They managed to escape, but the building was struck by the shelling. Flames spread across the floors, devouring everything they touched.

“We escaped with no documents, we just crossed the border illegally.” Firoza explains: her voice is plain, calm, but the words she says suggest how frantic that moment could have been. “I had brought all my papers to my office, since I should have gone to India for a new contract for a project. I thought that keeping everything there would be easier, but they got completely burnt when the Taliban hit it.”

The city of Herat. Photograph by Jim Kelly via Flickr.

“We fled with just a bag of clothes.” Fariba adds, “We needed to change them frequently so that the Taliban could not find us.”

Her husband managed to reach Fariba with their three children, but Firoza’s family was prevented from joining them by the fierce fighting which was shaking the city.

They escaped through a dangerous route, travelling for seven days on foot or by car, under the scorching sun, each of them holding the hand of one of the children, trying to reassure them they were going to a place where they would be finally safe.

PAKISTAN, AN UNWELCOMING REALITY

“We stayed in Pakistan for a year, waiting for our Italian visa, and could not apply for any kind of support.” Fariba remembers hiding constantly from the police: fearing that they could be arrested, they were caught in a deeply stressful condition, since undocumented refugees could potentially be sent back to Afghanistan. In such a situation they were not eligible for any kind of protection in the south-Asian country.

Pakistan hosts the largest population of Afghan refugees in the world. Some have lived in the country since the Soviet invasion whereas others arrived later, following the devastating wars that ravaged Afghanistan during the last 40 years.

The United Nations estimates that 3.7 million Afghan refugees reside in the country, though the Pakistani government believes the actual number is much higher, up to 4.4 million. Roughly a third of them are undocumented and, following deepening tensions which resulted in border clashes between Pakistan and the Taliban, they now face deportation.

In November 2023, when Pakistan’s “Illegal Foreigner’s Repatriation Plan” was announced, around 350,000 undocumented refugees were sent back to Afghanistan, where a major humanitarian crisis was unfolding, thus endangering their lives and putting them at risk of facing starvation, homelessness or even torture.

Herat, Afghanistan. Photograph by Anuradha Sengupta via Flickr.

Some of them were born and raised in Pakistan and had never experienced the reality of the Afghan conflict, while others, like journalists and NGO workers, had escaped from the country for fear of reprisal at the hands of the Taliban. Many of them are women and children, who are most at risk of ending up on the streets, exposed to diseases and freezing cold.

Among the refugees facing deportation there are people who are still waiting to relocate to third countries, mostly Western nations.

“While in Quetta, we could get in touch with some Italian friends: in the final months they helped us also economically, because we told them it was very difficult with the children,” Firoza says. During her time directing her women’s organization, she had contacts with Italian workers she had met in Afghanistan. “With the help of Caritas [a Catholic charity] and Confartigianato [Italy’s main organization of craftsmanship and small enterprises], we were granted asylum in Italy.”

But, Fariba’s husband could not join them. “Shortly after we arrived in Pakistan, my husband went back to Herat to tend to our house and bring some of our things to Quetta, but, soon after, the Taliban sealed the border and he could not get out of Afghanistan,” she says.

STARTING A NEW LIFE IN EUROPE

In October 2021 Firoza and Fariba arrived in Italy, grateful to the government, which had given them the opportunity to resettle in Friuli Venezia Giulia, near the Slovenian border. This region is home to 1,158 Afghans, the highest proportion in the country, who live among a shrinking local population.

Friuli Venezia Giulia, Italy. Photograph by Harrison Fornasier via Flickr.

In this part of northern Italy, where the mountains meet the sea and cultures with millennial histories blend together – mixing Latin, Slavic and German heritage – poor weather is something everyone is used to. No one worries about the wind hitting their eyes and the rain wetting their clothes, since they know where they can safely escape from the whims of nature. It is a place called home.

Caritas, which runs numerous facilities throughout the country and provides legal and social support to migrants and other marginalized groups, arranged accommodation for the women in a village not far from Udine, cultural capital of the Friulian-speaking minority.

Though, despite being welcomed by the local administration and taking part in social events that shone a light on the conditions for women in Afghanistan, Firoza and Fariba soon encountered hard times. Living in a completely different place where most people do not speak English and foreigners are not always welcomed, they had to move from village to village, before ending up in a historic town known in Italy for its Langobardic monuments and Roman antiquities.

Via Mercato Vecchio in Udine with its historic palaces and porches.

“We changed three houses and the children moved from one school to another, having a difficult time adapting and making friends at first,” Fariba confesses, “But in the place where we live now there are a lot of amenities, like the train and the Italian school. I’m very happy here.”

A BLEAK PRESENT FOR AFGHANISTAN

“My family is still in Herat and my eldest son can’t provide for all,” Firoza says with a sigh, “My husband is ill and my daughters are segregated in their houses. Before the Taliban takeover, I had my NGO and a lot of projects and incomes. Now everything has changed. When I left Afghanistan, the Taliban froze my bank accounts and also my children can’t access them and I am really worried for them.”

Before the capture of Herat, Firoza’s work provided a stable income for a family of seven, where the youngest son is only seven years old. As well as her involvement in women’s rights advocacy, she worked as a massage therapist and was an established cricket instructor, the first woman to start such a career in western Afghanistan. She taught cricket for five years to more than 600 girls.

Firoza Wahedi with the winning cricket team.

According to the UN Development Program, since 2021 the Afghan economy has shrunk by 27% and unemployment has almost doubled, leaving many households without an income to rely on. Rampant inflation affects many families, who can’t afford to buy basic goods as prices of food and medicines spike.

“Medicines are often found outside pharmacies, in local markets, where people sell expired products,” says Firoza, “Moreover, private clinics charge people fees most of them cannot afford. For example, an eye injection can cost up to 30,000 afghanis [₤326]. My husband needs them but they are too expensive, so he has to live like he is blind.”

Among those most affected by the deteriorating health conditions are women: in the 2020 Human Development Report Afghanistan ranked 169th on the Gender Inequality Index, reflecting unequal access to healthcare. With a fertility rate of 4.75 children per woman, Afghanistan bears one of the highest figures in maternal mortality, an indicator which has been worsening in recent years, reaching a ratio of 638 per 100,000 live births.

Looking on from their new home, the women know the situation for women in Afghanistan looks bleak.

“Islam doesn’t forbid studying,” Firoza objects. “The Taliban are trying to change the educational culture and say that, if in any book there is a talk about human body, girls must not read them. Despite the mass exodus of professionals from the country, they still prevent girls from reading anatomy books, saying it is un-Islamic,” she adds, alluding to the requirement that a woman should be attended only by a female health worker.

“When the Taliban seized Herat, we were working on a project concerning women’s health across the city and neighbouring villages.” Firoza recalls, “We provided free monthly medical assessment for pregnant women and for their children and free vaccinations too.”

“This project was called Mirā.” adds Fariba, “It was a very good project and 11,000 had registered in it. We had volunteers who travelled to remote areas to raise awareness among women about health issues for them and their children. It was meant to last for five years and be extended to all Afghanistan. Unfortunately, it lasted only one year.”

The Mira project was designed to help mothers and children access healthcare. Fariba Baloch was part of this project.

After the regime change, a ban on women working for NGOs was issued – for alleged breaching of Islamic Law – and such projects were closed down.

“This project received funds from India and after the Taliban takeover India didn’t accept to keep Mirā going. Moreover, we left the country.” Fariba loved working in the Mirā project, “I really wish Mirā could be reopened and could keep on working, because such projects are much needed there.”

In Friuli, both of them are taking Italian classes and studying hard to start a new life and find a job: Firoza is attending a course to become chef’s assistant but, desperate to support her family back in Afghanistan, she is longing to complete it.

Read more:

- Living in limbo: How refugees pass time at an asylum centre in Italy

- Beyond the refugee crisis

- Why are we giving up on girls’ education in Afghanistan?

Featured image by Gabriele Tirelli via Unsplash.