Just a few years ago, Ecuador was a peaceful eco-tourism hotspot. Last year, it had the highest murder rate in Latin America. In this report from Guayaquil, Danny Wiser hears the stories of three Ecuadorians – a former prison worker, a firefighter and a retired teacher – and finds many of the country’s citizens want out.

“This is going to be a long war, it is an asymmetrical war… it is a war with people who speak like you, who look like you, who live more or less in your neighbourhood and who are much more difficult to identify,” says TV and radio host Rodolfo Baquerizo Blum. “Therefore it is a very complicated war and with people who have no scruples about killing.”

In the southern part of Guayaquil an 11-year-old boy, Joaquín, came back from a long day at school. In the September sunshine he went to buy himself and his elder sister, who has learning difficulties, two bottles of cola for $0.25. On his way to the shop Joaquín was gunned down with 37 bullets.

In the same part of the city in December an armed gang showed up at a house and shot dead four children between five months and seven years old; their intended target was the house next door.

Just two months before, across the Guayas River in Durán, some children went to look for their ball which had gone astray. They told their parents they noticed a bad smell. Next to the ball they discovered a woman whose body was wrapped in bed sheets, dismembered and decomposed – presumably tortured before being killed.

For much of the world, horror stories like these occur once in a blue moon. In Guayaquil, events like these have fast become part of the daily news cycle as in 2023 Ecuador was given the unwanted title of the Latin American country with the highest murder rate, overtaking Honduras and Venezuela along the way.

A councillor at the Municipality of Guayaquil, Alberto Cajamarca, tells me: “Right now we have normalised the killings, the beheadings in the prisons, the fact that there is a hitman on the corner of your street, the kidnappings, the bribes and the extortions.”

A street in Guayaquil, Ecuador – Danny Wiser

With the majority of Ecuador’s brutality concentrated in Guayaquil, the city endured yet another day of terror on 9 January as a series of horrifying incidents took place, including gunmen forcibly entering the TC Televisión studio taking journalists hostage during a live newscast, armed attacks in five of the city’s hospitals, and the kidnapping of students at the University of Guayaquil.

Events both in Guayaquil and throughout the nation led President Daniel Noboa to call an ‘internal armed conflict’ against 22 narco-terrorist groups who have wreaked havoc across the whole country.

The gang network within Ecuador has expanded as a product of Ecuador’s dollarised economy, as it was in the interest of foreign parties to pay Ecuadorian gangs for their services in cocaine paste and other drugs, as opposed to in dollars which would see organised crime groups faced with a crippling exchange rate.

This decision enabled a rapid expansion of the narcotics network internally within Ecuador, and the more the money they made, the more those groups were tied into violent activity.

Another key facet in Ecuador’s rise in violence is a power vacuum that was created at the top of Ecuador’s most powerful organised crime group, Los Choneros, after the assassination of its former leader Jorge Luis Zambrano in 2020.

As a result of this, numerous splinter groups like Los Lobos, Chone Killers and Los Tiguerones came about and have been wreaking havoc not only fighting the state, but fighting amongst each other.

Cevallos’ Story

One factor behind Guayaquil’s descent into chaos lies in the enabling and assistance of gang activity from the country’s prison agency, SNAI (Servicio Nacional de Atención Integral a Privados de Libertad), widely accepted to be both an “inefficient” and “corrupt” organisation.

It is therefore no surprise that prison riots, as well as drugs and weapons smuggling have become commonplace at Guayaquil’s 70-year-old Litoral Penitentiary.

A former SNAI employee, Elena Cevallos, who began work as an educational inspector at one of Guayaquil’s four youth correctional facilities in 2022, described the prisons as “infected, rotten, damaged and corrupt”.

“Even the police came there to have sexual and romantic relations with the adolescents. The truth is everything was allowed in that institution.”

She recalls arriving to her shift and seeing that the police and her colleagues had got paralytically drunk with the young inmates but said that “obviously I could not report it for fear of my safety”.

Cevallos acknowledged that in her centre the administrative staff gave mobile phones to the teenagers, who outside the prison had often been groomed by the gangs like Los Tiguerones to commit crimes, most commonly kidnappings, drug trafficking, extortion and even murder.

Prior to the events of 9 January, the Andean nation was clearly on the brink of becoming a narco-state, with violent crime and corruption infiltrating every level of society.

Just a few years ago Ecuador had one of the lowest crime rates in the region and was once an eco-tourism hotspot with visitors flying into Guayaquil to visit Isla de la Plata, dubbed ‘the poor man’s Galapagos’. Today the Ecuadorian metropolis is more often avoided at all costs by tourists, and colloquially known as ‘Guaya Kill’ amongst backpackers mapping their route across South America.

What was once a country of peace, attracting half a million Venezuelans, now has its own citizens wanting out.

“I would like to move, really, but my economic situation is not the best nor do I have a passport,” the ex-SNAI employee says, “If in some moment I am given the opportunity to leave this country believe me, I would not think twice about it.”

She continues: “Psychologically there is a tremendous effect in the surge of anxiety and depression that has increased in our society. Here in Ecuador, not only in Guayaquil, people no longer want to go out to the streets, people who have money want to sell their businesses and move to other countries due to the extreme lack of safety.”

Homes in Guayaquil, Ecuador – Danny Wiser

What caused Ecuador’s descent into drug violence?

Some attribute the rise of gang power to the tenure of former President Rafael Correa who is currently in exile in Belgium.

Correa, who was fiercely opposed to foreign interference, removed the US navy base from the Western city of Manta which was serving as a control and deterrent against drug trafficking. Since then Guayaquil has become a major hub for trafficking cocaine in the region.

The crime figures under Correa’s leadership were deceptively low, and many believe this is because Correa turned a blind-eye towards narco-related activity.

Correa granted legal status to gangs Latin Kings and Ñetas as part of a so-called ‘pacification process’ which many saw as a green flag given to foreign organised crime groups to operate freely in Ecuador.

Correa’s soft-stance on the narco-gangs meant that

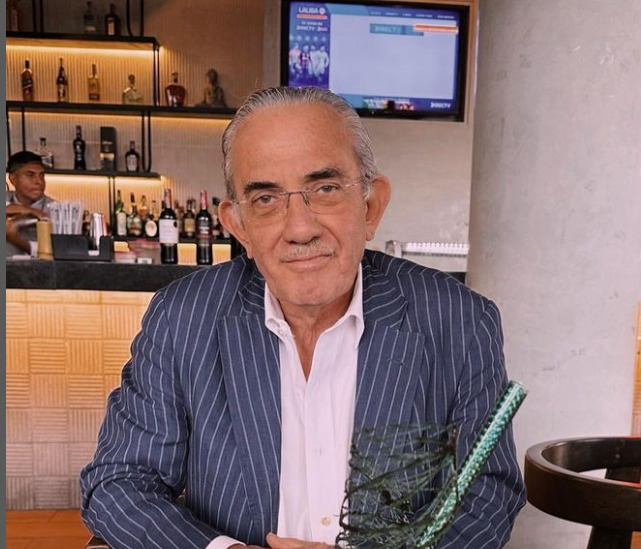

Ecuador TV and radio host Rodolfo Baquerizo Blum

Ecuador seemed like fertile soil for Mexican cartels from Sinaloa and Jalisco to bring their business because they would go relatively unchecked. And Ecuador is geographically sandwiched between the two largest cocaine producing nations, Peru and Colombia. TV host Baquerizo Blum describes the border between Colombia and Ecuador as “more permeable than Gruyère cheese”.

But many Correístas dispute the accusations that Ecuador’s current problems have their roots in Correa’s tenure as President, and instead pin the blame on the dismantling of the state by the subsequent administrations of Moreno, Lasso and are concerned by President Noboa’s lack of experience.

Batista’s Story

Like many residents of Ecuador’s largest city Guayaquil, Jonathan Batista recalls joyous memories of years gone by, celebrating the annual carnival with loved ones and strangers alike.

With water balloons, flour and foam launched in the air to mark the festivities, carnival in Guayaquil was once a time of colour, dancing and parades.

Families and friends would often come together to have barbecues and cool down from the blistering heat in their inflatable pools that residents put out in the street for people to enjoy.

In recent years carnival has become a more low-key affair in Guayaquil, with restrictions forcing people to either go to the coast or mountains to celebrate or to stay at home, as gathering in big crowds is unwise given the current situation in the city.

Beginning his work in the adjacent town of Samborondón 18 years ago, before joining the Guayaquil Fire Department, Batista has seen his beloved city undergo a “drastic change”.

The 35-year-old claims that his decision to join the voluntary fire service was something that came from his “blood” as his mother was a firefighter and so too was his maternal grandfather.

“Wanting to help without receiving anything in exchange was what they instilled in me,” says Batista who follows a great and honourable family tradition.

Though Guayaquileños (or ‘monos’ as those from the coastal region of the country are colloquially known) never claim Guayaquil to be the most beautiful place in the world, nor even in Ecuador for that matter, the Andean metropolis is famed for the hospitality of its people.

Once upon a time, a stranger would immediately become a ñaño/ñaña (a popular slang word in Guayaquil, derived from the Quechua for brother/sister) by simply being sat on the same table in a market as they tuck into the city’s varied cuisine.

Guayaquil became a popular stop for tourists on their way to Isla de la Plata, dubbed ‘the poor man’s Galapagos’.

Yet Batista’s love of the city has been tested in recent years as his profession has seen him become a high-risk target for the gangs who have infiltrated and attacked every institution within the country.

Those who work with civilian protection services like the fire brigade, the Red Cross and the police have become military targets in the eyes of organised crime groups, such as Los Choneros and Los Lobos, that terrorise the city’s streets.

One member of Batista’s brigade was robbed five times last year alone. Like almost every Guayaquileño, the volunteer fire station commander has also been a victim of the city’s increasing crime epidemic on a handful of occasions in the past few years.

Though he is brave enough to take on fires, Bastista is not immune from the perils of gang crime, and since 2019 he has been the victim of several attempted kidnappings.

The most recent incident last year saw 18 bullets fired into the tyres of his car where he was hiding close to his home.

Batista used his military training to navigate the kidnap attempt, protecting not only himself but his children and his mother who were inside his home nearby.

The father-of-three reclined his car seat, and managed the situation practically blind by carefully guiding himself with the live footage from the security video camera he installed into his rear view mirror. Instead of going directly back into his house after averting the danger, Batista drove on his flat tyres to the Citizen Police Unit to ensure that no gangsters would follow him directly into his house after the attack.

“What I thought about after this, once I got over the adrenaline, is what would have happened if I didn’t cover myself?

“If I didn’t react, if these gentlemen had kidnapped me, what would have happened to my children?

“You know that there can be consequences, you can get hurt and you can end up in the morgue,” he continues, “every action has a reaction; if you don’t react, you’re a dead man.”

Though seatbelts are rarely used as a safety measure in the Chevrolets that dominate Guayaquil’s busy streets, in recent years most people have taken a leaf out of Batista’s book, employing security systems in their vehicles to protect themselves, as drive-by shootings, car bombings and armed robberies have become commonplace.

Many armorize their car doors with extra material and have installed tinted windows so that the passengers and driver cannot be seen from the outside; nowadays it is accepted that lowering one’s car window, even in the blistering Guayaquil heat for fresh air, can be a death sentence.

In the same way that many Ecuadoreans have to implement various precautionary measures in their everyday life, firefighters have also had to make adjustments to their work in light of the increasing risk of narcoterrorism.

Hiding their names and covering their faces for fear of retribution is considered a normal safeguarding action for firefighters these days, and given the recent trend of emergency service workers specifically being targeted by gangs, they are even forced to use unregulated equipment such as bulletproof vests as part of their uniform, weighing them down further whilst tasked with responding to a blaze in an already heavy suit.

In light of the regularity with which gang bombings occur in the city, the Guayaquil Fire Academy has been training 300 of its firefighters on how to respond to emergencies when explosives are involved.

Batista explained that dealing with explosions is not always plain sailing as often when they arrive at the scene of a car bombing, an armed gang will be waiting for them.

He said: “Nowadays when we arrive at the site of an explosion, the gunmen are there and order us to ‘let it burn or we will kill you’.”

Aside from having to respond to regular gang bombings – with Batista citing a particular night of simultaneous explosions in the Alborada neighbourhood as a “disaster” – the fire service also receives plenty of calls with invented emergencies to lure them in.

Batista recounts an incident in which the fire service received a fake emergency call from an armed gang. Upon arrival the young gangsters instructed the firefighters to exit their truck and film them inside. Due to their threats, the firefighters complied and recorded the gang members dancing inside the fire truck, taunting the audience.

This video later circulated on social media, leading to attacks on the firefighters who were portrayed as accomplices of the criminals.

Guayaquil at night – by Jose Garcia on Unsplash

Gang crime in Guayaquil reached new heights on 9 January. Batista was in a meeting with the fire department authority in the afternoon when news broke of the terrorist attack during the live broadcast.

From the fire department building between Guayaquil’s main street 9 de Octubre and Avenida de Chile, gun shots could be heard being fired coming from the intersect between the aforementioned Avenida de Chile and Calle Escobedo.

Batista and his team began to guide people on the street, explaining where to go to avoid the gunfire. With streets closed, public transport at a standstill and no taxis available, Batista was stuck in traffic for 3.5 hours in a journey that would usually take 20 minutes from the city centre to his home in Mucho Lote.

As Guayaquil reached a sweltering 39°C, people risked heatstroke, sitting for hours in their crowded vehicles too afraid to lower their windows for fear of further terror attacks.

The pandemonium unfolding on the roads saw cars crashing into people’s wing mirrors as they desperately struggled to reach safety.

Comparing the chaos of Guayaquil that day to that of Gotham City, Batista explained that as a calm-natured individual for him the hardest aspect of the day was the communication issues that were unfolding as he attempted to contact his family.

Guayaquileños were panicking as they tried to reach their loved ones for a life signal but they couldn’t because the telephone lines had collapsed and so too had the internet due to too many people simultaneously accessing the network.

ZAPOTE’S STORY

Walking around Guayaquil, one will often find young children roaming the streets selling sweets. Though one’s heart will break seeing kids as young as four approaching asking for money, it is a well-known trap set up by the narco-groups to rob or assault those willing to take out their wallet to spare some change.

The infiltration of youngsters into the gangs’ activities is a relatively recent phenomena according to a retired deputy headteacher of a state school in the northern part of Guayaquil.

Having taught in the school for 40 years, Carmen Zapote says that in recent times children aged 11 are regularly being caught with drugs by sniffer dogs that the police have brought to the school, finding narcotics hidden in their underwear.

“When I started at the school there were no drugs at all. The most you could find would be a boy who went to the bathroom to smoke cannabis. Then came an era in which we were inundated.

“A group of 7th grade students contaminated the entire school – we are talking about children who just finished primary school!”

The eruption of drugs and violence in the school, led the Spanish literature teacher to retire early. With inspections of rucksacks every morning in her former school, teaching hours were lost to this long and arduous process.

That said, Zapote recognises it is a necessary security measure as they once found a boy with a pistol in his bag. The 68-year-old’s biggest concern is extortions.

Having been a victim of this herself, forced to change her phone number as a consequence, she is pained to see businesses providing a salary to the “savages”, due to their regular threats of bombings or killings.

“The money they steal, through murder and through extortion, is money that is drenched with blood.

“They squander that money which belonged to the children and families who have nothing to eat in a place where work is scarce, and when there is work it is low paid.” She exclaims:

“There are people in Guayaquil who live on just $1 [a day]!”

Most businesses and services remain closed; even if they are losing money from being shut, when open they run an arguably higher risk of losing more money through extortion.

Photo of Guayaquil – by Anthony Surace via Flickr

As a state of emergency has been declared across the country, with a nightly curfew enacted for the nation’s armed forces to carry out its operations as part of President Noboa’s iron-fist approach to rooting out narco-terrorism, people are terrified to leave their homes even during the day.

Zapote says: “Before, one would go out and eat quietly sitting down, you can’t do that anymore. All those things have been lost from our Ecuador. The ease of being able to go outside has gone because you don’t know if the person next to you is a criminal or if a bullet will hit you.”

Like most Guayaquileños, Zapote dreams of being able to go back out to the market to eat her beloved encebollado (a fish and cassava stew) for breakfast without being ‘on high-alert’.

She says: “Now there is a psychosis, there is a fear, a suspicion. You can’t have your door open; it must be locked. There are often shootings. Children can’t be outside.”

Zapote and people from her generation are distraught seeing how crime has taken over what was once a stable nation.

On 9 January, together with her 88-year-old mother, she watched the live broadcast on TC Televisión as armed men waged yet another act of terror. Just like every time she watches the news, Zapote’s “anguished” mother had tears rolling down her face.

“She saw how her beautiful land, country and city is being destroyed. She sees how children are dying.”

Zapote adds: “We just long for our country to return to previous times when everything was peaceful.”

Main image by VV Nincic via Flickr.

Read More: