This memoir of fleeing Palestine as a child was highly-commended in our 2020 Warwick Law School writing competition. Salma Eleyan takes us from Palestine, through Egypt, to Europe, sharing her mother’s pain of repeated visa refusals in their search for a home.

One of my first memories is of my panicked mother shaking me awake in the dead of the night. She let me go back to sleep when she saw that I was okay, and I woke up the next morning to shattered glass glittering all over the floor.

It turned out the building across from our flat had been bombed when it was dark, and my uncle had called her immediately. He heard too many stories of children passing away in their sleep from the aftershock of the explosions.

My mind tries to recreate the relief that must have enveloped her when I stirred in response. She tells me she felt like she had just narrowly escaped every mother’s worst nightmare.

I don’t know what the final straw for my mother was. Was it that instance?

Was it when my ballet teacher locked me and a group of confused kids in a panic room after hearing the Israeli airstrikes? Or was it my abusive father, forcing his old-fashioned Arab ideals onto her?

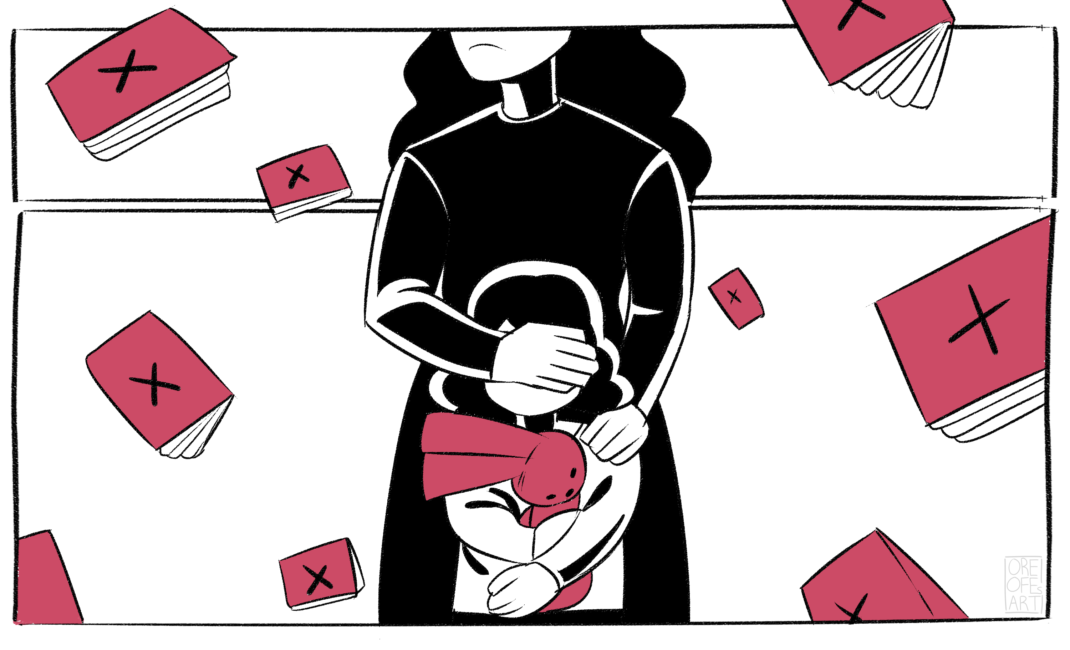

Regardless of what it was, she knew it was time to leave. I wasn’t old enough to understand the severity of our departure. At only four, my biggest concern was making sure my stuffed bunny was safe in my little backpack.

For my mother, us leaving meant her losing the support system that was her family. It meant turning her back on the life expected of Arab women, and raising a small child in a foreign country. All on her own.

I vividly remember the sweltering sun burning my little, curly-haired head. We were crossing the borders from Palestine to Egypt on foot. To our side it felt like thousands of people were huddled together at the border point, their bodies creating a barrier that blocked any cool air from saving my skin.

Read more: Life in occupied Palestine

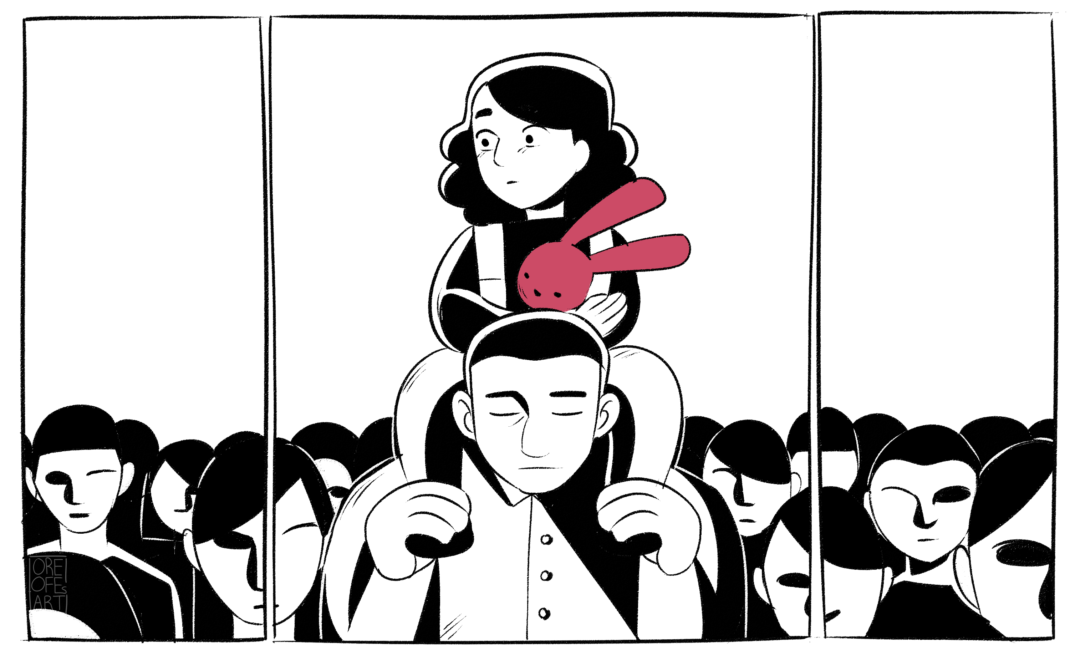

My mother’s cousin let me sit on his shoulders for most of it. We waited and waited and waited. I felt no anticipation at the time — only boredom. It was different for the two adults accompanying me.

After hours of standing, in what I would now consider inhumane conditions, the border opened. All hell broke loose. It was like a stampede of caged zoo animals smelling freedom, and then clawing their way out.

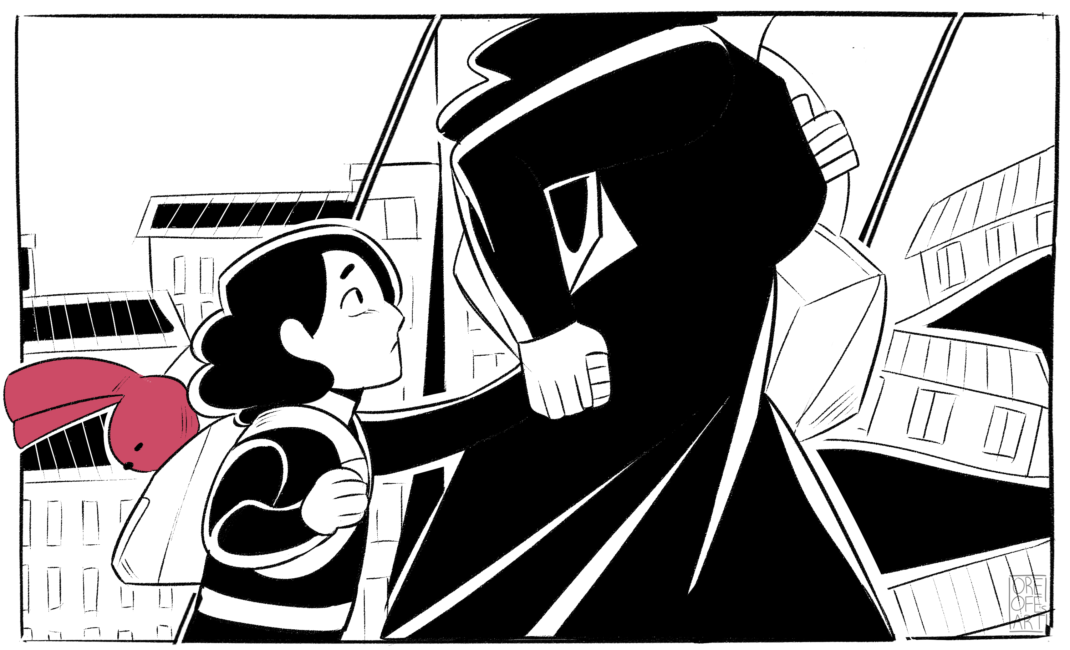

My mother stumbled and fell among the crowd. One of the Egyptian guards from the other side steadied her back onto her feet. The fastest-fading victory scene in history.

It did not get easier. We were allowed to stay in Egypt only because of the fact my mother was completing her PhD there. The facts that she was a human being, with a young child, in need of a home were irrelevant.

Apparently you have no right to exist in any country unless you are of capital value.

Read more: Poems for Palestine

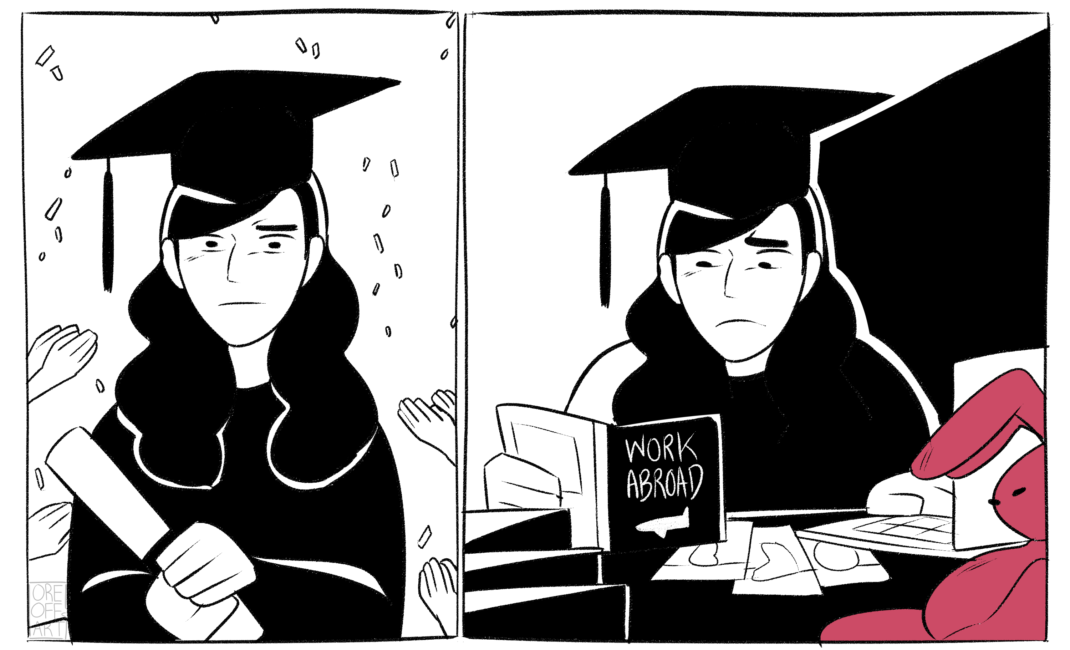

Unfortunately, once she had finished her PhD, my mother’s application for a work visa was rejected – and instead of celebrating her academic accomplishment, she found herself making arrangements for us to move, again.

She was a tax-paying individual, contributing to wider society as a school teacher, but her Palestinian origin outweighed that and we were forced to leave. At least, that’s what it felt like.

Our Palestinian passports meant that that was only the first time. We spent the following years in a feverish cycle of settlement and rejection. It was difficult enough for us to persuade any country to allow us to enter, and then even more difficult for us to convince them to let us stay long enough for it to become our “forever home”.

The phrase “visa application” re-appeared in my life every six months, like a toxic ex-lover. My mother tried to keep me uninvolved in the process, living in the hope that we would be granted stay. That she wouldn’t have to break the news that I would have to move again.

She always felt responsible for all the tears I would shed saying goodbye to my friends, the consequent tears of starting a new school and being anxious as a pre-teen.

We moved between countries three more times before finding our way to England. And although I gained life experience and knowledge of cultures, I lost my sense of identity and my own culture in the process. I know I am a Palestinian from the blood propelled by my heart, but the western ideals that drive my brain create a disconnect. I can call England my home but moments of alienation and discomfort will remind me that I am not like the rest of my peers.

There is technically a happy ending. I am safe and I am settled. But I still carry the consequences of my experiences. My mother still has a scar on her right knee from the day we fled.

All images by Oreofe Morakinyo.

More stories from our 2020 writing competition:

- Teaching emergency English classes for refugee children in lockdown

- Move! A Rohingya child dances for hope in the world’s largest refugee camp

Read more: