What is it like to be autistic? And why are a growing number of women receiving late diagnoses for autism? After spending most of her life not knowing she was autistic, our writer describes her experience of being neurodivergent. In this honest and original piece, she explores the discrimination she faces because of preconceptions, stereotyping and a lack of adequate support.

The lights are like sandpaper. Each noise piles on top of the one before it. The clattering of plates, the child dropping a whole pile of cutlery with a crash, the beeping of checkouts, the insistent buzzing of the lights, the repetitive clanking of wonky-wheeled trollies, the babies screaming, the constant background chatter, the rustling of plastic packaging, the squealing complaint of the broken checkout conveyor belt in aisle 5. The clattering, crashing, beeping, buzzing, clanking, screaming, talking, rustling, squealing, buzzing, beeping, chattering, building up and up and up, piling higher and higher in my head. I can smell coffee. I can hear a child scream as a chocolate bar is prised from their fingers. It’s too bright. I’ve forgotten to get bread. The lights scrape my eyes. I can’t do this. I need to leave. Now.

I’m autistic, and this is a trip to the supermarket.

I always knew that I was different. When I was young, the blissful ignorance of childhood hid the giggles and the stares, the comments behind my back. When I was older, I noticed, and I knew.

I figured I knew what it was. I just wasn’t “girly” enough. I didn’t want to wear the scratchy pink tutus and serve the imaginary ladies imaginary cups of tea in imaginary bone-China cups. I didn’t care. It was more fun mixing potions by myself, mumbling spells as I sat cross-legged in a muddy puddle at the end of the garden. I had friends, anyway – the fairies living in the tiny stone huts I diligently rebuilt after every storm.

But I got older, and I began to care. No matter how hard I tried, I wasn’t quite “right”. Somehow, everyone else had been given a guide, a script to this all-enveloping performance, and I’d just been shoved onto the stage, stumbling blinking into the lights and faced with the expectant looks of my fellow cast.

I watched, I copied and I learnt.

But I got older, and something still wasn’t right. I’d see the pictures of parties, shopping trips, brunches, weekends away, all of my friends hugging and grinning at the camera. I wasn’t invited. I couldn’t seem to join in when the girls were giggling about their latest crushes, picking the petals from daisies in some bizarre ritual (“he loves me, he loves me not”) or coating their eyelashes with the dark, itchy mascara that made me rub my face until I resembled an exhausted panda. I went to a sleepover, threw up after less than an hour and promptly returned home. Unsurprisingly, I wasn’t invited back.

She’s weird, they say. Maybe she’s not quite all there. A bit slow. Or a genius. She’s just not trying. She’s being difficult on purpose. She’s rude. She’s just looking for an excuse. I’ll accept “weird” – and while I’d love to accept “genius” too, that’s sadly not true.

However, what I am is “autistic”. Put simply, my brain works differently. I’m more sensitive to sounds, and bright lights. I sometimes find it hard to socialise in the way people expect. I can be more literal than most people, and I might find it tricky to work out hidden meanings or unspoken expectations.

People don’t seem to like the word “autistic”. Even when you’ve been diagnosed, and when they know, and when they believe you, there’s a reluctance to say the word. ASD, my mum always says euphemistically, when she can’t avoid it. People don’t like to talk about it and, particularly, people don’t like to talk about the things many autistic people find hard. Either you’re low-functioning, and they dismiss you and do them for you, or you’re high-functioning and can’t possibly need any support. “Stop taking things so literally,” my dad huffed the other day, exasperated as I somehow failed to understand that obviously he had requested I do the opposite of what he actually wanted to happen.

Job interviews are the worst. “Your CV is great!” they tell you. “Your cover letter was so impressive!” they say. Then you sit there as they ask question after question and the words come out jumbled. You aren’t really sure what they’re asking but you try, and you ask them if there’s anything else they would like to know, and they shake their head but you see your failure written on their faces ahead of the inevitable email. It’s fine. You add it to the folder, clearing your inbox of your inadequacy.

“You don’t look autistic,” they say.

When you feel nothing. Not bored, not tired, not happy, sad, angry, frustrated. You just exist, waiting. Someone has pressed pause, and there’s nothing you can do. You can’t hold on to a thought. When you speak, the words are as muddled as the thick, gloopy mud inside your head. You had plans? Forget about it. This is today.

You’re not ill. You just can’t.

But what are you supposed to say to your seminar tutor to explain your absence? What do you tell your best friend who’s been looking forward to drinks all week? How do you explain to your future employer that no, you’re not ‘pulling a sickie’, you just can’t today?

“It must be very mild,” they tell you.

The friends you’ve never made because you thought that “let’s get coffee!” meant getting coffee, and you don’t like coffee.

The time the teacher asked if you thought you knew better, and you said you did, because you knew you were right that the UK voting age was 18, not 16 (you were right, but she didn’t care).

The food you burnt because you were told to watch it, and you did – watching the tendrils of smoke curl upwards and the edges slowly crisp and blacken (you did what you were asked to!). The time your friend joked you should run under the closing barriers at the level crossing as a train approached and you did, tears in your eyes, watching their face suddenly whiten (how were you supposed to know they didn’t mean it?).

“I’d never have guessed,” they exclaim.

Just because I can speak and live largely independently, doesn’t mean I’m not autistic, and that I don’t have any challenges. My brain is different, undoubtedly. But I don’t think it’s disordered. But, just like people won’t talk about the challenges, they won’t talk about the good things either.

I’d like to think that, at least sometimes, my literal understanding makes me funny (even if sometimes I don’t intend to be). My tendency towards black-and-white thinking means I have a strong sense of justice that I physically feel through my entire body. I tend to be pretty honest too.

Nothing can compare to the happiness I can get from the simplest sensory delights – running tiny smooth pebbles through my fingers, burying my face in a soft, fluffy blanket (as long as it hasn’t been washed with scented detergent), walking through long grass in bare feet and gently wiggling my toes into the cool ground. I’m great at thinking outside of the box and coming up with innovative solutions to problems.

While experiencing very strong emotions can be difficult and painful, it can also allow me to feel pure, intense, unadulterated joy. I love that I can get so intensely absorbed into an interesting topic that I completely forget about everything else for hours on end.

So, that’s me. I have no idea what you were imagining, but perhaps someone quite different.

Why is it, then, that these misconceptions remain so prominent?

Thirty-five years after he first appeared on cinema screens (twelve years before I was born), Dustin Hoffman’s Rain Man continues to have a profound effect on the way the general public think about autism. I’m not a man. I’m terrible at maths, I don’t like collecting things, and I definitely can’t tell you more than three interesting facts about anything at all, let alone talk your ear off about airplanes or something. I don’t live at home with my parents. I’m definitely not a savant. I actually don’t have any talents at all (or at least, no more than anyone else). I am at university, living independently, and with a successful romantic relationship.

But still. I’m autistic. And nobody knew until I was 20. Not even me.

Let me paint you a picture. Imagine a four-year-old boy living just down the road from you. He had an elaborate train-shaped cake for his birthday party (which no other children attended), and any time you see him he tells you at great length about Thomas the Tank Engine. Often, he’s sat outside in the front garden, lining up his model trains for hours on end. He loves maths, and his parents tell you that they don’t want to brag, but he’s definitely a genius. Sometimes, you see his parents dragging a screaming child in ear defenders around the local supermarket. He’s autistic. No surprise. He’s what you expect.

But let me describe someone else. She was a gifted, kind and curious child who loved reading, even when other kids her age were still struggling to learn, and she adored writing poetry. She was clever at school, but very clumsy and quite fidgety, and teachers found her to be overly sensitive and rather dramatic. She hid in the toilets at break times. She grew up, found herself fitting her personality to the situation she was in and the people she was with. She still loved writing. She was lonely, anxious and depressed and still felt like she never fitted in. She sold 3.4 million books worldwide, mostly to an audience of adoring teenage girls. She’s autistic.

This is author, Holly Smale, who was diagnosed at the age of 39, and told her story here. Holly Smale. Melanie Sykes (diagnosed aged 51). Christine McGuinness (diagnosed aged 33). Sara Gibbs (diagnosed aged 30). Susan Boyle (diagnosed aged 51). Kate Fox (diagnosed aged 42). Anne Hegarty (diagnosed aged 45). Hannah Gadsby (diagnosed aged 38/39). Maybe you recognise some of these names off the TV, off the covers of books on your shelves, or off the news. All of these women were diagnosed with autism, long into their lives and careers. Comedians, writers, singers, poets, TV personalities… autistic women are everywhere.

Read more: Disabled people are worthy of love.

Currently, around three times as many men than women are diagnosed as autistic. Often, autistic women are only identified after years of misdiagnosis, being passed from support service to support service and accumulating a smorgasbord of misdiagnoses along the way – an alphabet soup of anxiety, depression, eating disorders, BPD. They have spent years trying desperately to fit in, but always falling slightly short. Maybe they’ve gone through life wondering why it is they find everything so much harder than everyone else – or maybe they’ve realised they’re autistic, but been dismissed by friends, family members or even the GP who thinks back to that four-year-old boy and says, “you can’t be autistic”.

Women can’t be autistic. Except, we are.

The autistic spectrum is diverse, and we need a full spectrum of autistic representation – which includes women, and nonbinary people.

You might ask if it really matters. After all, if someone has made it to their 40s, 50s or even later without a diagnosis, what’s the point?

Even high-profile researchers are quoted explaining that you only need a diagnosis if your autism is interfering with your ability to function and causing you distress. Others argue that autism is becoming so over-diagnosed as to become meaningless. That four-year-old is autistic, sure, but maybe all these late-diagnosed women are just jumping on the trend?

Not only is this argument misleading, it is dangerous. Imagine knowing that you’re different, growing up feeling that there is something “wrong with you”, unable to fit in, struggling with friendships and holding down jobs. If you don’t know why, it’s so easy to conclude that you are the problem.

Research suggests that high levels of undiagnosed autistic traits are common among those who attempt suicide.

Newly diagnosed adult women report having experienced significantly higher levels of suicidality and depression than the general population. Late diagnosis kills.

Last week, my friend questioned me about getting an autism diagnosis. “Do I just go to the GP?” she asked me. I had to laugh. Current waiting times for a first diagnostic appointment are upwards of two years – and that’s once you’ve managed to convince the GP that yes, women can be autistic and yes, you really do want a referral. Private diagnoses can cost nearly £1,000.

“Congratulations, you’re autistic,” I was told. Like so many women, all I felt was a great sense of relief. Finally, I knew that I wasn’t the problem. I wasn’t just broken. There was a reason, and there were other people like me. And finally, I could get the right support.

“You might like to read these books,” the doctor said to me. Excellent, I thought – there are few things I enjoy more than deep diving into a topic, reading books and following link after link right into a corner of the internet that clearly hasn’t seen a visitor since 2002. Except, apparently that was it. The books were the totality of the support on offer (and I had to buy them myself).

Despite the fact that at least 1% of the world’s population is autistic, – around the same percentage as there are ginger people – autistic people and autism researchers agree that support is inadequate. On a global level, the UN has highlighted discrimination against autistic people, with “treatments” or “cures” that often amount to torture.

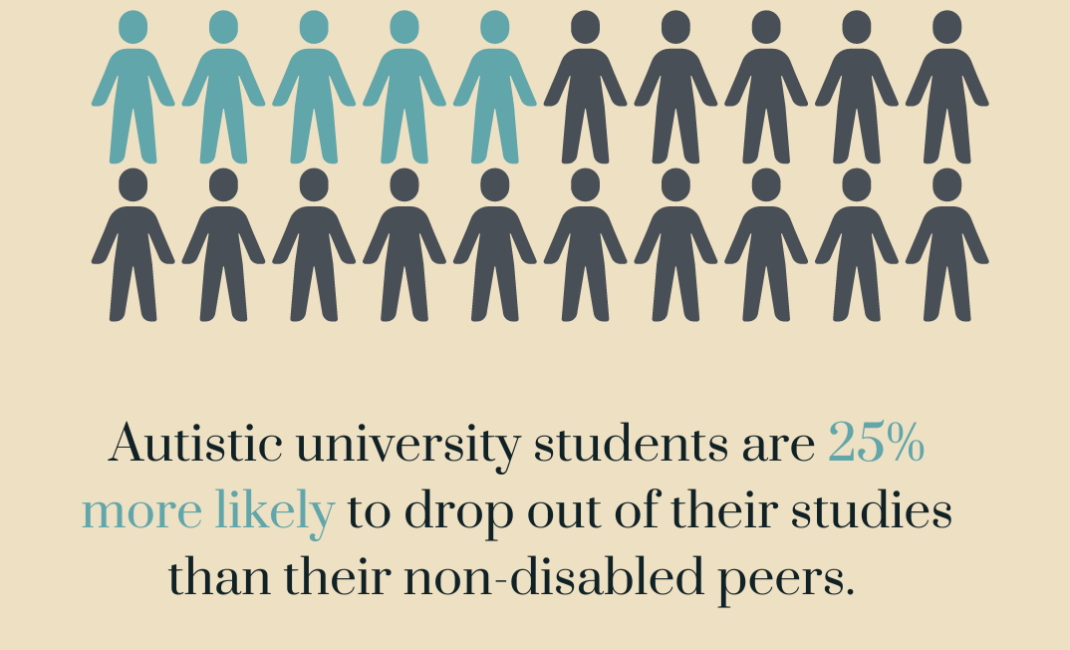

In the UK, only 22% of autistic adults are in any kind of paid work. Autistic university students are 25% more likely to drop out of their studies than their non-disabled peers. Even a typical work environment may be traumatising. A 2014 study suggested that at least two thirds of autistic adults will experience suicidal ideation – and autistic women are three times more likely to die by suicide than their non-autistic peers.

Over 2,000 autistic people are currently detained under the Mental Health Act – on average, they will be detained for five years. Many of them do not need to be there – but no other services are available.

This is what happens when there is no support.

Office for National Statistics. Infographic by Lacuna

Society does not like autistic people, it seems. I think of the articles explaining to desperate parents how to “cure” your autistic child. I remember how studies that suggested it’s possible to reduce autism diagnosis numbers have been heralded positively across mainstream, reputable media outlets. I am told that I “lack empathy”. I think of anti-vaxxers, who would apparently prefer to have a dead child than an autistic one. And of the GP surgeries who applied blanket Do Not Resuscitate orders to their autistic patients during the pandemic.

This is what it is like being autistic. The way my brain works can be amazing and beautiful. I am capable, strong, independent, unique and funny. I am resilient, because I have to be. But I – and other autistic women – need support. And we need you to understand what it’s like.

All illustrations by Oreofe Morakinyo.

Read more: