With Human Rights Watch, Anna Neistat spent two decades investigating more than 60 of the world’s most dangerous conflict zones, eventually starring in an award-winning documentary about her work. Now, as Amnesty International’s senior director for research, she gives an in-depth interview about Australia’s treatment of refugees on the island of Nauru, Russia’s young protest movement and what the future holds for humanitarian work.

Coming of age in Moscow during the collapse of the Soviet state, Anna Neistat was an aspiring lawyer passionate about Russian criminal reform and the jury trials. Accepting a position as Moscow director of Human Rights Watch (before going on to hold other positions) would send her on a journey through scores of conflict zones, from Chechnya and Ingushetia to Afghanistan, Yemen and Syria, as part of the organisation’s Emergencies Team or “E-Team”, which featured in the eponymous 2014 Netflix documentary (see below). Today, serving as Amnesty International’s senior director for research, Neistat reflects on the challenges and opportunities for human rights advocates.

You’ve been working in humanitarian disaster zones for more than 20 years now. How can you get used to that?

No matter how hard some aspects of the work are you get used to it. There are always moments throwing you off-balance: there is always a witness, a victim, a place that pushes you to the limits of your emotional resilience. Overall, you can only do this work if you’re 100% professional in the sense that you do not allow your emotions to take over your mission, which is to collect information in a way that could potentially be used for international prosecution. But if there’s a moment when you stop feeling shocked by the death and suffering surrounding you, it’s probably the time to stop for a while, because it basically means that you’ve burnt out. You’ve lost something that is crucial for being an effective advocate.

Have there been moments when you burnt out?

Not really, but I switched from Human Rights Watch, where I was doing exclusively field work, to Amnesty at what probably was the right moment. By that time, I had been essentially doing war zones and conflict non-stop for almost 14 years. And I’ve pretty much covered every possible conflict that happened during that period. I wasn’t looking for a way out, but I was getting to a point – I don’t know if it was burn-out or frustration or despair – which I had previously been able to deal with, and it was good for me to step back for a little bit and get a broader perspective. That’s what I got at Amnesty. I still very much focus on crises, but I stepped into a more managerial role, which was timely. But I miss field work a lot and I’m trying to do that, too, when my competence is required.

Are the challenges now greater than at the start of your career?

Definitely. At the start of my career human rights advocacy was at its acme. Despite Chechnya and Kosovo, there was definitely this feeling of an upward movement.

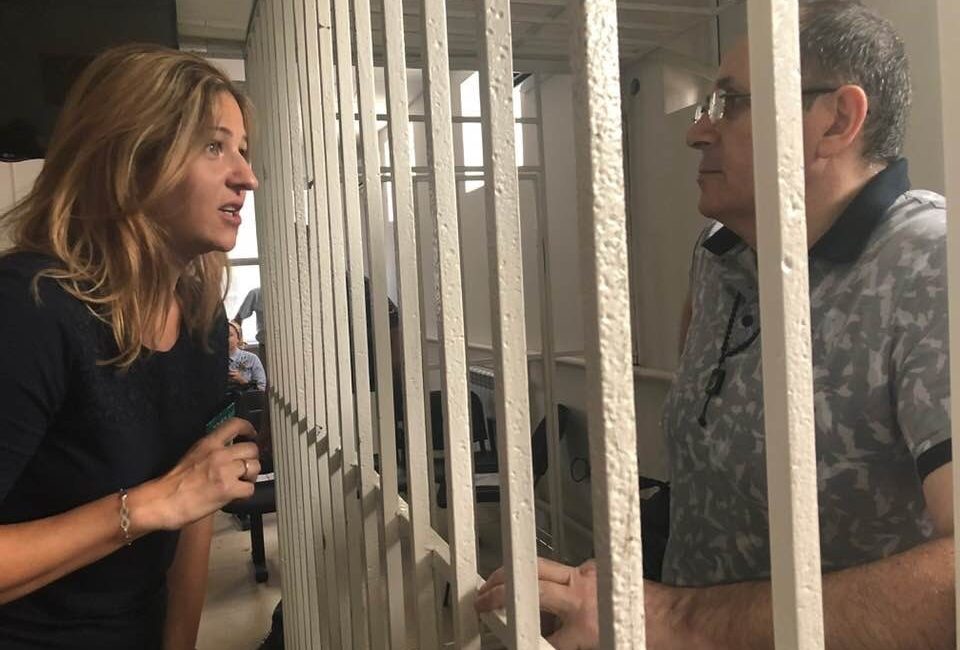

Anna Neistat of E-Team

The International Criminal Court came into place, and at the time that was a huge deal. Now, everyone’s wondering what’s going to happen to it but the idea that there would be a standing tribunal to try representatives of sovereign nations individually was incredible. It’s something that had only happened on an ad hoc basis in history, and there was always controversy about it, be it Nuremberg or the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) or Rwanda (ICTR). And afterwards, there were so many new international instruments addressing the rights of people that had never been addressed, be it the LGBTQI community or domestic workers.

As I went through my career, I saw a growing recognition and understanding of international obligations. Even when I was talking to Chechen field commanders, it’s not to say that they weren’t doing horrendous things—they were—but they were very aware of potential accountability. Over the last couple of years, so many red lines have been completely pushed back, such as the use of chemical weapons or attacks on hospitals – something that was not so much part of the equation ten years ago. And the number of deadly conflicts is growing again. Something we need to think about much more is rhetoric. Trump brought it front and centre but he is not alone. There is Modi in India, there is Erdogan… And it’s not the “usual suspects”, not necessarily the Russias and Chinas of this world, but also countries human rights organisations were almost relying on as their partners – Great Britain, for that matter. When they are turning 180 degrees on their commitments, it creates a completely different level of challenge for the human rights movement.

What new challenges have emerged during the past decade?

Certain innovations present both challenges and opportunities. The role of technology in both human rights protection and human rights violations is something we haven’t even started touching upon, partly because there are very few people who understand how it works. We are all completely terrified by how big data can be used to violate human rights, but most of us don’t have the skills and understanding required to deal with it. And same goes for issues such as automated weapons, or the challenges which automation in the labour market creates for human rights. I think it’s the field that’s going to be front and center of human rights work in the coming years. And this is not even to mention climate change. We’re facing an existential threat to the entire system of human rights. I strongly believe we’re up against a challenge like never before, perhaps since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Anna Neistat (right) interviewing in Afghanistan – Human Rights Watch

With the current hostility towards migrants, what mechanisms could help find a more humane asylum policy?

The system is already there! There are systems, there are protections, there are refugee conventions. Part of me finds it completely unbelievable, what’s happening with the “refugee crisis”. It is clearly an artificial notion of crisis, rather than a reality. Look at Australia and Nauru. In Nauru and on Manus Island, in offshore detention, there are barely 2,000 people. Australia is arguing that if they don’t do offshore detention, boats will continue to come. But even when they do come, at the height of boat arrivals, we were talking about 20,000 people a year — that’s nothing.

Yet if you look at Australian media, you get a sense of the entire country being overtaken by refugees. And this is exactly what you see in Europe as well. There are very specific methods of how this notion is being created, in terms of pictures and terminology used – the “fake news”, for that matter. The whole security argument doesn’t stand any laugh test. But again, this is being used very effectively. And of course, the growing number of terrorist attacks including in European cities doesn’t help. Whether or not refugees are in any way involved in that absolutely doesn’t matter, because it is a matter of how it’s being spun by the media and by politicians.

A couple of years ago, at Amnesty, we were looking primarily at resettlement: pushing countries to increase their resettlement quotas given that there were more and more refugees and arguing that it was entirely possible if we expanded the list of countries responsible for resettlement. Now, given that the US, the largest resettler for many years, has practically withdrawn from the programme altogether, we are switching to community and private sponsorship as an answer to the refugee crisis—the Canada model if you like. It requires the state’s commitment, but also the participation of the population. It does seem that what populations around the world think about refugees is very different from how their governments are trying to present what they think.

You personally uncovered signs of brutal treatment of refugees in Nauru by the Australian government, which allegedly amounted to torture. How and why did you end up going there?

Nauru represented the whole notion of offshore processing which is something that Australia actively propagates. The EU-Turkey deal and the deal they’re trying to reach with Libya are similar: “Let’s pay somebody else to make sure refugees do not come to our shores.” “Let’s reach a political deal that would basically prevent people from even stepping foot on our soil so that we do not have to deal with them. ” It’s a crucial notion to contest in the context of the “refugee crisis”.

Refugees are held for a year or more in the fenced and tented refugee processing centre on Nauru where people who have tried to seek asylum in Australia were forcibly sent – Amnesty International

On the other hand, Nauru was a mission impossible, and I kind of specialise in that. It’s an independent state, but also an island of 20 square kilometres and a population of 10,000, in the middle of nowhere. In order to even physically get there, I had to travel for three days. It’s also been completely closed for any sort of outside scrutiny. Before I went, Amnesty applied for an official visa six times and was rejected. The journalist visa application fee is $8,000 and 100% of the time you get rejected. The only journalists who have been there—and they are few—were from Australian pro-government outlets. In addition, when I went there—and this has changed since, thanks to us—everybody who worked there, whether they were doctors, security guards, social workers, teachers, all of them were essentially sworn to absolute silence by Australian law: the “Border Force Act” was essentially a gag rule threatening anyone talking of the situation on Nauru with two years of jail.

As we were looking for options, it turned out that Nauru and Russia have a no-visa agreement, and so my Russian passport came in handy. Nauru was one of the very few states which recognised South Ossetia in 2008. Another dimension to it is that it’s a major money-laundering exercise for organised crime—we’re talking billions of dollars. Little did they know! And it was a very difficult exercise: I knew I had very little time and had no idea how to start interviewing people from 12 different countries with no context.

What did you discover in Nauru?

Over 400 asylum seekers and refugees remain in cramped tents in Australia’s refugee processing center on Nauru. Temperatures in the tents regularly reach 45 to 50°C (113 to 122°F) – Amnesty International

Having worked in several warzones, I had rarely seen something as desperate and horrendous as Nauru. People’s mental health is horrible: they are all trying to commit suicide, self-harming, swallowing razors, drinking washing liquids, because there is no way out. It’s a one big open-air prison for women, children and men. Children don’t go to school because they get bullied, harassed and constantly attacked by locals, who just rape women and take their cellphones with complete impunity… There’s really no healthcare. So lots of people are suffering from pre-cancerous and cancerous conditions, heart disease, diabetes. Lots of women have gynaecological problems, and there is no gynaecologist on the island. And it costs about $400,000 AUD per person per year to keep them there. It’s just insane. [According to a 2016 study by UNICEF and Save the Children, between 2013 and 2016, Australia has spent more than 9.6 billion AUD dollars on their policy of offshore processing through Manus and Nauru and onshore detention of asylum seekers.]

We came to the conclusion that this amounts to torture, because of the nature and intent. It’s not random! Australia is super clear that they created this system to prevent the boats from coming. Their argument is that so many people capsized near Australia’s shores that they don’t want to create a pull factor. But the idea that you would create what is essentially an open-air prison where you would so badly treat people who you already recognised as refugees (the majority of them have refugee status, so you aren’t even questioning their claim for refugee protection) in order to send a message to others to not come…this is completely perverse. I was told that an Australian minister once came to Nauru and didn’t take any questions. A community leader who had been governor of his province in Afghanistan said: “I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t even open my mouth. He was just pointing a finger in my face and telling me to call my village and tell them not to come.” So the intention is completely blatant.

What happened after the report?

The good news is that it sounds like the beginning of a success story.

We put a lot of effort into advocacy with Australia. When we released the report, we basically became the number-one enemy of the state: I had rarely come under that level of attack in the Western world. When you say: “Our senior director of research went to Nauru,” it creates a slightly different level of importance for news outlets. So there were endless interviews on CNN and BBC, but also NPR and PBS. That level of publicity also made it very difficult for Trump to go back on the refugee deal signed by Obama with Australia, in which the US would take some refugees from Nauru and Manus in exchange for Australia taking in several Cubans, Costa Ricans and others. Our programme “business and human rights” dug into all the companies providing services on Nauru, since Australia subcontracts all the services there. The latest one that was running the whole operation was a Spanish company called Ferrovial. So we published a report specifically on their corporate accountability which contributed to them withdrawing. Others withdrew as well and Australia, to this day, is finding it very difficult to find someone willing to work there because it became such a huge reputational issue.

What human rights issues were you most focused on at the start of your career?

I was really focusing on issues that I considered quite fundamental. For instance, I was completely blown away by the fact that jury trials were just introduced in Russia. A lot of what I did on the radio was basically pro-jury trials propaganda. I worked with a judge who was one of the authors of the law on jury trials – legal enlightenment, as we call it. At the same time, I was working on my PhD thesis about how in the early Soviet days, literature was used to indoctrinate legal consciousness—people’s perception of the law—as back then there was no mass media. At the same time as people were fighting for literacy, literature was the medium to introduce new ideas. It was fascinating how suddenly the idea of collective punishment or the denial of the presumption of innocence became a very accepted norm, although it hadn’t been that way. People accepted it although none had read the criminal code! My work on the radio was focusing on the academic work I was doing but in reverse: I was trying to reverse the consequences of what I found in my academic research.

And then when Human Rights Watch hired me as the Moscow director, that was the intended direction of travel. They were going to move away a bit from documenting Chechnya. But 20 days after I joined them, I ended up on a plane to Ingushetia and it was clear that [violence in Russia and former Soviet republics] was going to be our focus.

Anna’s mission to Chechnya to observe the trial of human rights campaigner Oyub Titiev – Amnesty International

Tell me about your time with the Emergencies Team, starting with the Kosovo War where they first began reporting ongoing abuses in real time.

I moved to the emergencies unit three years after I was appointed the Moscow director, partly because so much of my work revolved around conflict (Chechnya took most of my time). Back then, the idea that you could investigate and do a press conference the next day was unheard of. Instead of using the information to write a 150-page report and release it a month later, you would do an immediate digest and press release… It’s actually surprising now, 17 years later, that it has become a mainstream and common methodology.

The award-winning documentary E-Team, which honours American photojournalist James Foley who shot footage for the film before he was killed by terrorists

Following the war in Kosovo, we kept on perfecting it and bringing in new dimensions. It’s great to be quick but there are so many challenges, such as starting to compete with the media. So how do you find your niche when you’re in the same place as the CNNs and BBCs of this world and their massive crews? Usually, the crisis zone is an entire circus where you end up running into the same journalists over and over again. We call it “the vulture club”. We always praise ourselves for our methods of verification: every report goes through five stages of editing and re-editing. We struggle over every word to make it accurate. It’s very different when you have 24 hours at best to produce it, instead of six months.

Then the question becomes: do we do advocacy in real time? We did start picking up the phone pretty much from the field and calling officials in Brussels or in the UN urging them to help stop whatever was happening at that very moment. Overall, we got a lot of acceptance from the international community because they did want to know what was happening on the ground in real time and they rarely had their own people. I can think of quite a few situations when this approach made a difference, including in South Ossetia, where this real-time advocacy helped stop the looting of Georgian villages. We just called all the relevant people and it got back to the Russian peacekeepers who closed the road to the villages. It was very funny to come back the very next day, ask why the road was closed and hear that the situation was all over the media now.

I’d never argue that this is the only acceptable solution: lots of situations require a very well-developed report and a lengthy investigation, such as reports on corporate accountability. These investigations usually take months, if not years, and the reports are long and boring, because every word is going to be scrutinised by corporate lawyers, who are much scarier than most governments.

How do you feel about the state of Russia, with the constantly mounting pressure against protesters and opposition activists?

I feel incredibly depressed, not surprised perhaps, because I don’t think Russians have ever internalised the concept of democracy or the value of human rights. I think that [following the Soviet Union’s fall], they appreciated certain benefits that came with that, such as the ability to travel or have a free market, but it was implemented very wildly, no one can deny it.

It is depressing to realise how far behind we are today, compared to the Europeans, much more so than during the late 19th century. My frustration with Russia basically goes back to the assassination of Alexander the Second, on the eve of the day when he was supposed to sign the first Russian Constitution. But as the Russian expression goes, history has no a conditional mood: whatever happened, happened. It was just amazing that we got to live through this period of insane freedom and parting with the Soviet past. My parents just couldn’t believe that they’d finally see that day. Watching this massive totalitarian system that had been completely unbreakable crumble and fall gave me the drive and incentive to do this work for the rest of my life.

Read more: Did Pussy Riot Destroy Russia’s Anti-Putin Movement?

I am fascinated by Russia’s protest movement. It’s animated by young people, something which I really couldn’t have expected. I watched my friends, especially those who have kids in their late teens, being frustrated about this new generation, who grew up with Putinism. We did not expect anything from them, and suddenly these 17-year-olds show up at anti-corruption protests. What is it that makes them do it? They’ve been subjected to the most intense propaganda since the fall of the Soviet Union. But they aren’t susceptible to it because they don’t watch TV or read papers.

What do you think of the scope of Russian propaganda?

The Russian propaganda machine is crazy. There used to be a TV show called “International Panorama” in the USSR, the most ridiculous show ever, providing the Soviet take on international events. They even had different labels for the different kinds of rebels, depending on who we supported: some were freedom fighters, others were “posobniki imperialisma” [enablers of imperialism]. When I watched it again I thought to myself, it was almost good journalism compared to what is being done now. Especially around the events in Ukraine, they’ve invested in Russia Today, Lifenews, Sputnik: it’s just a completely different level [of misinformation]. But interestingly, this generation doesn’t even know about that, because they never watch Russia Today or Channel One. And forget about the papers, even when they’re online! The state still does not control the internet the way China does and that’s why one of the first protests last spring was linked to a video put up by Navalny on social media, because this is where they live and get information from.

Anna Neistat in Kyrgyzstan – Human Rights Watch

So why isn’t Russia’s youth afraid to protest?

Today’s youth don’t have this KGB-phobia of previous generations. Most of my generation didn’t have any interaction with KGB, but there’s an almost genetically-implanted fear of a KGB officer walking into your room. When I was detained in South Ossetia and interrogated by a Russian general who was clearly part of the system, I felt extremely uncomfortable. But these young guys, they just don’t have it! They don’t know our history well, so they are not afraid. And that is very dangerous for the regime. In Russia, throughout history, power was based on fear. But now, the youth haven’t read The Gulag Archipelago [by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn]. In some ways, it’s healthy because they treat Russia as a normal society and I think there’s a lot of hope in that.

You’ve said that your work was “a mix of a criminal investigator, a journalist, and a social worker”. You don’t think it has clear boundaries?

I was trying to describe the dilemma that you’re always facing. On the one hand, you’re trying to play the role of a criminal investigator: you’re collecting facts. So you have to go back to the same question four different times and test the testimonial capacities of your witness. If someone tells you that they saw something happening 50 meters away on a river bank, you have to know what time of the day it was and whether they were wearing glasses.

But in order to be effective advocates, we need to bring forth the stories of those we interview. After all, they’re telling their tragedy and it’s their justice you’re fighting for. Even when we anonymise testimonies, these aren’t just victims of human rights violations, but very real men, women and children. They have individuality which needs to be brought into reports. This is where the journalist in you comes forward, as you’re telling a story and describing what they look like and how they spoke. And you talk to people who have been through some of the worst traumatic experiences. When you interview traumatised witnesses you can’t just go through your list of questions and leave. And I always preach that we should be very conscious that we don’t re-traumatise people with our questioning. It’s just the nature of the work, but there are ways of dealing with this. In some cases the interview is re-traumatising, but it may also be therapeutic. For many witnesses, it’s important to tell the story for the first time, which becomes an act of healing as well.

As you’re going to be one of the few people with whom they’ll interact about those issues, the way you respond matters enormously. And it’s so culturally sensitive: you have to know whether it’s appropriate to give the person a hug, or to make eye contact. Now, we have additional pressure: also being a videographer or a photographer, and asking the interviewees whether we can use their case to raise money. These are the people for whom we work, so it’s reasonable to use their individual stories to ask for support, but it’s not necessarily an obvious thing for them. You can only imagine how people normally, myself included, would feel after doing an interview when asked if their story and photo could be used for fundraising.

How do you see humanitarian advocacy work evolving in future?

Anna Neistat

The power of local groups will continue to grow. When I travel to various parts of the world, I see local groups emerging—groups of lawyers, women, the civil society–and this is going to be a game changer. The presence of international groups on the ground (the whole Amnesty slogan is “moving closer to the ground”) is going to become the norm. It used to be that everybody just travelled from London to do their mission, spent two weeks, and flew back. That’s no longer the case. We have regional offices all over the world and part of the reason why is to be closer to the pulse of local communities.

Generally speaking, this direction which the human rights movement is taking implies that it won’t be seen as something imposed by the West, including by Western human rights organisations, but much rather part of local, regional and national dynamics. In some cases, this transition will make it harder to work on certain issues—and people will focus on others, be it economic inequality or issues that are less political and more relevant to a given community—but it almost doesn’t matter what particular human right the people care most about: so long as they care about at least one, we can bring them on board. As long as there’s this growing acceptance of human rights and human rights protection as concepts, which cannot be traded for security or political gains, then I think we’re on the right path.

Main image from Anna’s mission to Raqqa supplied by Amnesty International.

- For content like this direct to your inbox, subscribe here.