This World Refugee Day, we honour the resilience of millions of refugees from Syria to Eritrea, Myanmar to Afghanistan. Over the last decade, the world has seen the largest mass movements of people since the end of the Second World War. Millions of people have been forced to flee their homes due to war, persecution, and poverty. This collection of journalism, fiction, and videos brings together some of the most significant stories we have covered in that time, following the journeys of refugees, many leaving Africa, travelling across the Mediterranean, and attempting to start new lives in Europe.

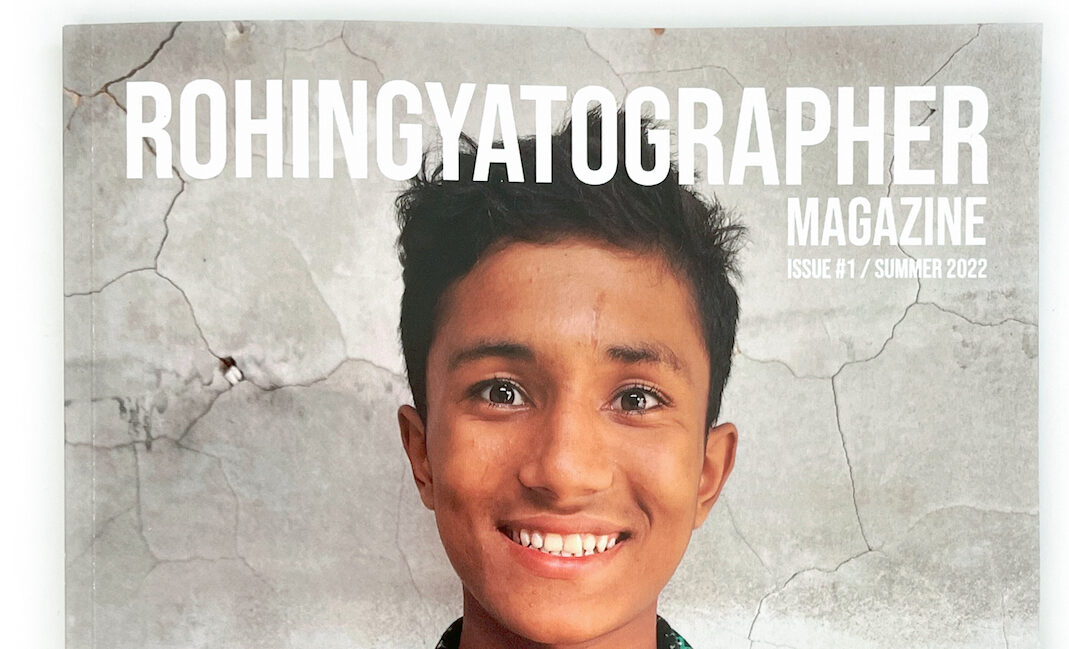

Rohingya refugees are using photography to tell their own stories

“We want people to see us as human beings, just like everyone else, and we want to share our hopes and dreams, our sadness and our grief with others, to make connections.

In the world’s largest refugee camp, Rohingya refugees are using cameras and mobile phones to document their lives for a new magazine. Find the full story here.

Joy, grief and resilience in Makhmour refugee camp

Many believe the location in Makhmour was chosen to send the refugees to the desert to die, but instead, they built a community.

In northern Iraq, photographer Paul Trowbridge visits Makhmour refugee camp – a camp the size of a small town. He finds that having fled persecution in Turkey 30 years ago, the refugees are still not safe from bombs. But, despite difficult circumstances, these photographs show the camp’s residents carrying on and finding ways to maintain life with normality and hope. Find the full story here.

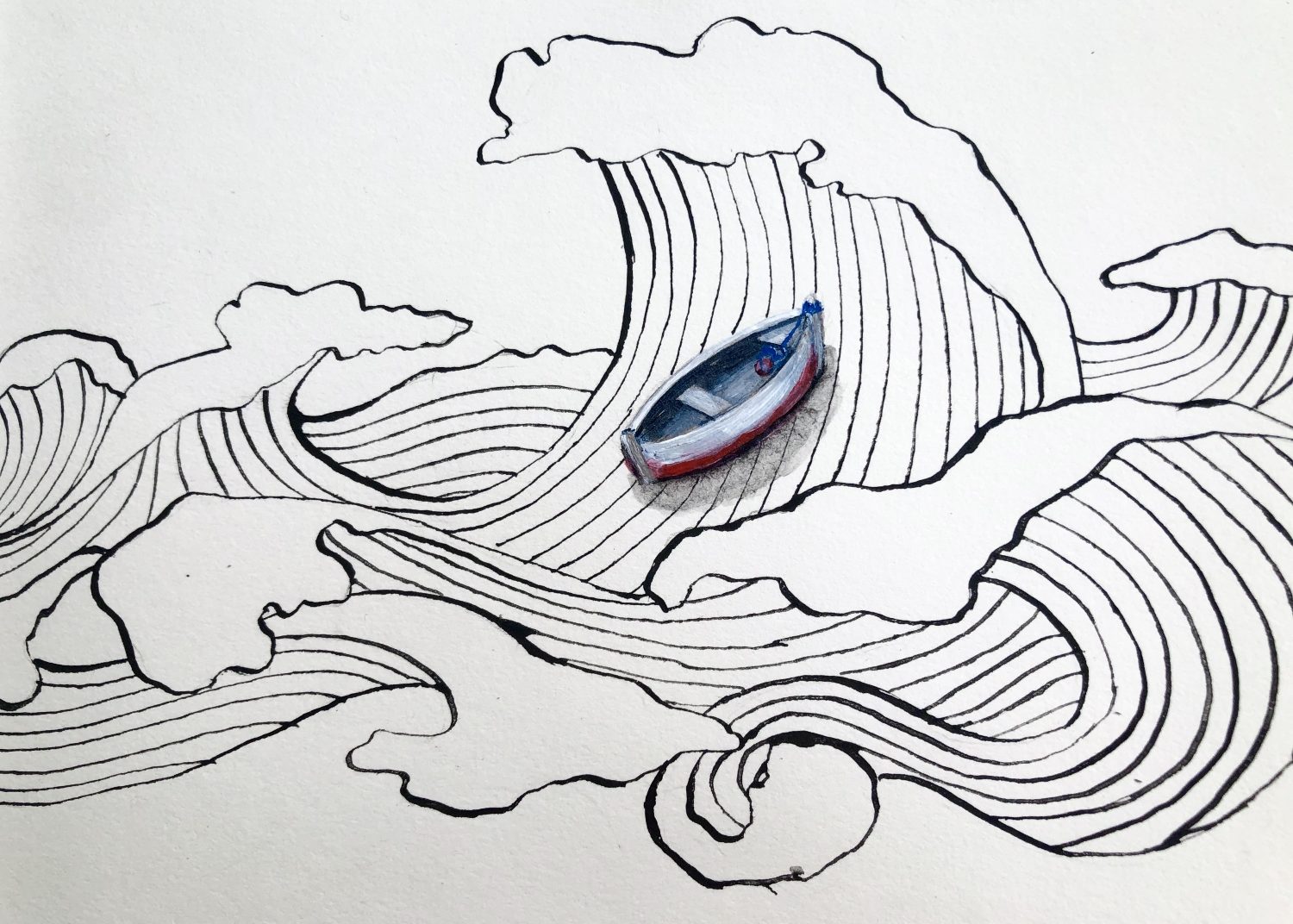

Crossing the Mediterranean: What do 270 migrant and refugee interviews reveal about Europe’s approach to migration?

In Greece the people we met had the hope of a new life in Europe but by the time many had reached Berlin, the hope seemed dashed.”

Crossing the Mediterranean Sea by Boat is a vital report inspired by the personal stories of hundreds of migrants and refugees. A team of interviewers travelled to key European sites to find out whether new migration policies designed to save lives are effective or ethical. Dr Dallal Stevens shares the team’s findings from speaking with hundreds of people on the move. Find the full story here.

How can we trace and name each refugee who has drowned in the Mediterranean?

We analysed bodies, remains, clothes, pictures from Facebook, and DNA,” Cattaneo explains. “I found a lot in people’s pockets: money, personal documents, bags with dirt from their native land, library cards and blood donor cards.

In Italy forensic pathologist Cristina Cattaneo was working to identify some of the 20,000 refugees who have died or gone missing while trying to cross the Mediterranean. Relatives post pictures of their missing loved ones in kiosks in their hometowns while those who can afford it travel to Cattaneo’s lab to find answers. Journalist Greta Privatera hears their stories and asks why Westerners who have seen families fight tirelessly to find missing relatives after 9/11 or the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami fail to imagine that the families of Eritrean, Senegalese or Syrian people are desperately looking for their loved ones too. Find the full story here.

The Foreigner: One family’s journey from Pakistan to the UK

It began with a wave of muttering, gradually picking up pace until eventually, I was washed over daily with an unstoppable tsunami of hatred.

This vivid short story gives us a glimpse into one family’s journey from Pakistan to the UK. Our 16-year-old writer presents a sensitive and spirited description of immigrant life, based loosely on the experiences of his grandfather. Find the full story here.

Attempting to put down roots in a Syrian refugee camp

The sea of tents was giving way to concrete structures, featuring blue tiled walls and cement etched to give the impression of crazy paving. The camp residents were tired of waiting to find out what the future held for them and had decided to create a future for themselves.

When Aveen, a Syrian refugee and mother, found solace in gardening, she saw it as a way of putting down roots in her refugee camp in Kurdistan. How do families, like Aveen’s, find a sense of permanence while living long-term in temporary camps? Adam Robertson Charlton tells Aveen’s story. Find the full story here.

Bhasan Char: Prison island or paradise? Are Rohingya refugees being denied their right to freedom of movement?

Perhaps the most alarming aspect regarding Bhasan Char is the limited right to movement enforced upon its Rohingya residents, triggering some to desperately attempt to escape from the island.

The government of Bangladesh plans to move 100,000 Rohingya refugees to the island of Bhasan Char. The plans not only raise questions about freedom of movement, but about the unlawful detention of refugees. Following a visit to Bhasan Char, our authors, two researchers, explore the issues on the island and beyond. Find the full story here.

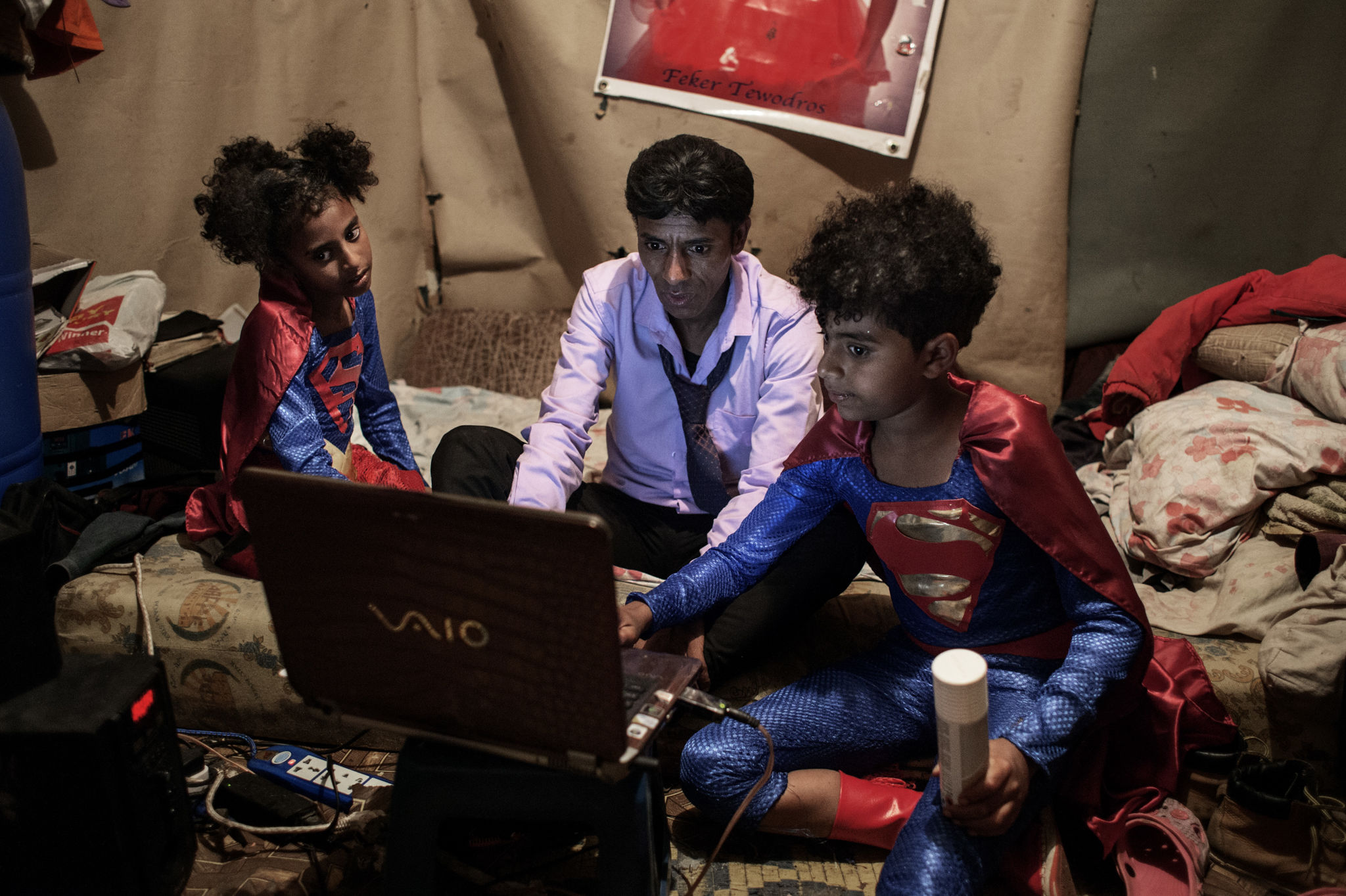

An Eritrean in Ethiopia: Teddy Love’s story

Teddy waltzed into the lobby like a rock star, with a huge smile and masses of self-confidence. He launched into the conversation, ruminating at great length on love, understanding, bridges, suffering, freedom, passion, family and a better world.

Singer “Teddy Love” is one of tens of thousands of Eritrean refugees living in Ethiopia. In this short film, photojournalist Gabriel Pecot captures the story of this enigmatic father-of-two who is using music to transcend borders and unite people. Find the full story here.

Fleeing Palestine – and what happened next

For my mother, us leaving meant her losing the support system that was her family. It meant turning her back on the life expected of Arab women, and raising a small child in a foreign country. All on her own.

This memoir of fleeing Palestine as a child was highly commended in our 2020 Warwick Law School writing competition. Salma Eleyan takes us from Palestine, through Egypt, to Europe, sharing her mother’s pain of repeated visa refusals in their search for a home. Find the full story here.

“Never again”: The defiant Rohingya of Bradford

When I was seven years old a bad cyclone hit the camp,” recalls Salah. “My brother and I used to dig a hole in the ground, go down and bring a lamp and cover it until the rain had stopped. When we used to come back up, it felt like coming up from a grave. I’ll never forget this.”

“The international community always says never again”, says Salah Uddin, a Rohingya man born in a refugee camp in Bangladesh, “but we are letting genocide happen in the 21st century.” Find the full story here.

Waiting & Hoping: Refugees in Ethiopia

When I first met Nakfa she didn’t mention her trip to Sudan or what happened to her there.

More than 500 refugees drowned in the Mediterranean Sea during 2017 alone. Politicians responded by tightening EU border security and outsourcing controls to third countries. Meanwhile, refugees continue to move. In this four-part series, Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi tells the stories of people risking their lives to reach Europe and the factors affecting their decision-making. Find the full story here.

Beyond the refugee crisis

In Fatima’s situation, people can wait months and sometimes several years for a final decision on their migration status

From Eritrea, Sudan, Afghanistan, and Vietnam, refugees languished without papers in camps and communities in Europe, often destitute, trying to regularize their status, while the EU scratched its head deciding how to deal with them. After more than one million people reached Europe by sea in 2015, many fleeing Syria, the continent was thrown into crisis. Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi visited Sicily to discover how the system would cope now with a million new arrivals. Find the full story here.

Once upon a time, a hope called Idomeni

Ahmed sold everything he owned in Syria to pay for the journey to Europe. He paid around $600 to cross the Turkey-Syrian border and $5,000 to reach Greece with his wife and his 4 children.

In 2016, the village of Idomeni in northern Greece was a key transit point for refugees travelling from the country to northern Europe. When Macedonia closed its border and built a fence to prevent people crossing, thousands were left stranded in the village. It soon became Europe’s largest informal refugee camp. In May the Greek government began the evacuation of the camp. Journalist and photographer Dario Sabaghi witnessed the final days of the camp and interviewed soon-to-be evicted residents. Find the full story here.

“The Home Office is coming”: Life within the UK asylum system

I had never seen such desolation as I did in his eyes when he whispered, “I want to go home. I have no hope. I have nothing here. I have nothing.”

Graduate Olivia Konotey-Ahulu reflects on three years of volunteering at a night shelter for refugees and asylum seekers. Her overview of the hazardous UK asylum process is peppered with her own encounters as she explains how men and women have come to be at the shelter and asks where they can hope to go next. Find the full story here.

Why are police in Croatia attacking asylum seekers trapped in the Balkans?

The EU provides funds for humanitarian assistance to migrants and asylum seekers in Bosnia and Herzegovina that, while helpful, cannot justify turning a blind eye to neighbouring member state, Croatia, blatantly breaking EU laws and ignoring violence committed against those same people.

Hearing increasing reports of police brutality against refugees on the Croatia-Bosnia border, Human Rights Watch demanded action from Zagreb and the EU Commission. Find the full story here.

Watching the clothes dry: How life in Greece’s refugee camps is changing family roles and expectations

The expectation for women to be primary caregivers was something I particularly noticed when running women’s activities on Samos. There was a stark difference between the daily classes – which would fill up with men attending alone, as agents distinct from their families in camp – and the women-only sessions, where accompanying children were almost always expected, and had to be considered in every session plan.

On the Greek Islands where refugees face long waiting times and a lack of adequate facilities, women are being pushed to the margins of camp society as children are deprived of education and safe places to play. While governments and the EU fail to provide satisfactory support, and NGOs fight to fill the gaps, how can we stop a generation of women and girls with high hopes of independence and careers from being forced back into domestic roles? Find the full story here.

MOVE: A Rohingya child dances for hope in the world’s largest refugee camp

Ma always says that you never walked your first steps; you danced them.

This story about a Rohingya child forced to flee her home, won the undergraduate prize in our 2020 Warwick Law School writing competition. Inspired by her work on a Save the Children campaign for justice for the Rohingya people, Amber Shah interweaves tender moments and tragedies in this clearly purposed piece. Find the full story here.

Alone in Italy: Life after the shipwreck

People look to Europe for help and with hope but the reality is different

In April 2017, over 200 refugees died after two rubber dinghies were sunk off the coast of Libya. With the arrival of spring and good weather conditions, it was likely that more boats would leave Libya for Europe in the coming months. Indeed, within days of the last sinking, rescuers discovered several boats carrying 1,000 refugees. All but one woman survived. What happened to the survivors once they landed in Italy, tired and in shock after long journeys? Lissalina Marwig tells the story of Amadou, a survivor she met on the streets of Catania. Photography by Kelly O Brien. Find the full story here.

In pictures: The human and environmental toll of mass Rohingya migration

In the western world we tend to think that we as humans are separate from our environment. But the truth is we are part of it. And when we think in this way we can see that the suffering of human beings is the suffering of the environment, and vice versa.

In Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, photojournalist Gabriele Cecconi was struck by both the human suffering and environmental degradation. Here he shares a photo essay revealing the toll, on both the people and the place, of forced mass migration to an area devoid of vital infrastructure. Find the full story here.

UK immigration detention: the truth is out

Britain is the only country in Europe without a time limit on how long it can detain people subject to immigration controls.

Successive governments have ignored and dismissed complaints of suffering in UK immigration lock-ups. In 2015 undercover footage revealed guards talking about the women in their care at Yarl’s Wood detention centre and a report found that the UK uses detention “disproportionately and inappropriately”, despite receiving far fewer asylum applications than its European neighbours. Looking back, with current concerns over the UK’s new Illegal Migration Bill, what has been learnt? Find the full story here.

Will Covid strip what few rights the Rohingya refugees have left?

“Every day I think that I would have been better off dying on that day next to my two brothers”

Since one of the fastest-growing migrations in recent history, the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh have been living in a climate of uncertainty and mistrust. After being confronted by a global pandemic and the prospect of being banished to an island for quarantine, Francesc Galban and Mohammed Sahat ask – did the Covid crisis strip the last remaining rights of the Rohingya people? Find the full story here.